When Anti-Lynching Law Was a Tool of Oppression

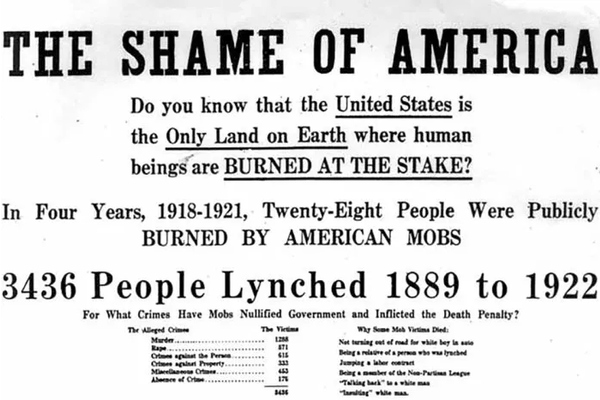

Recent news that the U.S. House of Representatives overwhelmingly (if not unanimously) passed the anti-lynching bill that advanced by passed the Senate last year has been greeted with some measure of relief. Many feel that finally, we can put to rest the era of legislative shame when southern Democrats scuttled any attempt to make mob violence a federal crime.

We cannot know for certain if such a law, implemented in the early twentieth century, would have saved lives. After all, the states where lynchings occurred had laws against murder, property damage, assaulting police officers, and other crimes that were often part of the total lynching event, but the will to enforce them was often lacking. Federal anti-lynching legislation might have only accelerated the transformation of lynching from a public spectacle into the quiet assassinations that became common following World War II. But the fact that Congress was unable to overcome regional intransigence and declare lynching an evil worth suppressing has been a cause for righteous indignation since the moment Leonidas C. Dyer introduced his first anti-lynching bill 102 years ago down.

Where the federal government failed, some states succeeded in passing their own anti-lynching measures. However, this does not mean that these states were particularly enlightened, or that these measures actually functioned to save lives. In fact, such measures often reflected a trend described by historian Michael J. Pfeifer in The Roots of Rough Justice: Origins of American Lynching. According to Pfeifer, legislators across the nation “reshaped the death penalty in the early twentieth century to make capital punishment more efficient and more racial, achieving a compromise between the observations of legal forms long emphasized by due process advocates and the lethal, ritualized retribution long sought by rough justice supporters.” Perhaps the best example of this was Arkansas’s Act 258 of 1909.

Titled “An Act to Prevent Mob Violence or Lynching within the State of Arkansas,” Act 258 stipulated that, “whenever the crime of rape, attempt to commit rape, murder or any other crime, calculated to arouse the passions of the people to an extent that the sheriff of the county believes that mob violence will be committed,” the sheriff was required to notify the district or circuit judge in order to request “a special term of court in order that the person or persons charged with such crime or crimes may be brought to immediate trial.” Said judge, upon finding that “the apprehensions and belief of the sheriff are well founded,” was to arrange for an immediate trial set for no more than ten days from receipt of notice. However, there was no punishment for a sheriff or deputy who allowed a lynch mob to kidnap and murder someone in his charge, and neither was there any special punishment laid out for the members of said mob. The only thing this bill accomplished was to expedite a trial—specifically, regarding those crimes which, at the time, could warrant the death penalty—while the spirit of mob violence was still in the air.

For example, following the arrest of three black men for the December 28, 1923, murder (and alleged rape) of a white woman named Effie Latimer in the Arkansas River bottoms near the Oklahoma state line, violence erupted against the black “colony” of Catcher, resulting in what has become called the Catcher Race Riot. Mobs threatened to lynch the three men and murdered the father of one of the men. Some burned down black homes, desecrated a black cemetery, and issued warnings that all black residents of Catcher should flee the area. While this violence was ongoing, the first murder trial was held, in accordance with Act 258, on January 4. The trial lasted exactly one day, and the jury deliberated about ten minutes before rendering a verdict of guilty and a sentence of death against defendant Charles Spurgeon Ruck. The next trial, that of William “Son” Bettis, occurred the following day and also resulted in a quick sentence of death. The third defendant, fourteen-year-old John Henry Clay, testified against the other two (possibly under duress) and received a life sentence of hard labor, though he died in prison four years later.

And thus we see how Arkansas used its ostensible “anti-lynching” law to transform the “bad violence” of the mob into the “good violence” of the state, to transform lynching into officially sanctioned execution. But the law was not even effective at preventing actual mob violence. In fact, in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, on May 24, 1909, less than two weeks after the bill had been signed, a mob lynched Lovett Davis despite the local circuit judge pleading with them and promising to order a special grand jury at once. Following the June 19, 1913, lynching of Will Norman in the Arkansas resort town of Hot Springs, the local circuit judge put out a statement insisting: “A trial could have been had in 24 hours after the negro had been incarcerated in jail…. It would have been a much better lesson had he been executed after a fair trial, not by self-appointed executioners who had neither legal nor moral right to take away his life.” But those self-appointed executioners were never apprehended or prosecuted despite performing their deeds downtown in the full light of day.

In fact, lynchings increased in number following the passage of Act 258. While there were four lynchings recorded in Arkansas in 1909, the next year saw more than twice that many. One could argue that, by reflecting what Ashraf H. A. Rushdy, in The End of American Lynching, called the “lynching for rape discourse,” Act 258 served to justify the very violence it was designed to prevent. After all, it lists rape first in its list of crimes “calculated to arouse the passions of the people,” despite accusations of murder being employed far more often to justify lynching at the time. Because Act 258 essentially legitimized the state’s violence against African Americans, it also legitimized the mob’s.

So while it is certainly all well and good to celebrate the present effort to implement, finally, a federal anti-lynching law, it would do us well to remember the “success” of state-level anti-lynching legislation. Such laws can serve as a warning to us about the ability of the state to reflect the spirit of the mob, even while touting the values of “progress” and “civilization.”