The Life and Times of Flamboyant Rock Music Impresario Bill Graham

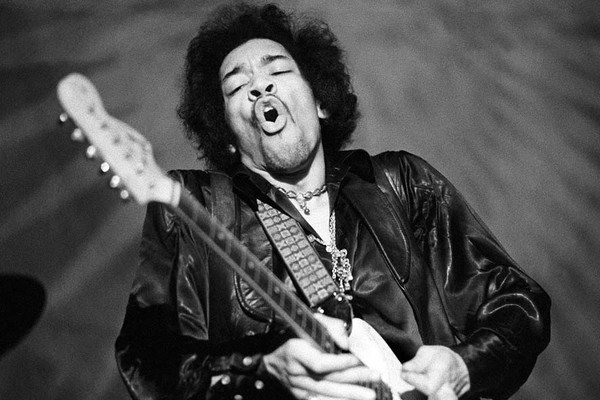

Baron Wolman. Jimi Hendrix performs at Fillmore Auditorium, San Francisco, February 1, 1968.

Gelatin silver print. Iconic Images/Baron Wolman

You remember rock music promoter Bill Graham. Sometime in your life you read about him, saw his photo in a newspaper or magazine or went to one of the thousands of rock and roll shows he produced from coast to coast. Even if you never went to one of his rock shows, you were influenced somehow by his work. Regardless of your age, you were a witness to the legacy of Bill Graham. You may think you know all about him—friend of Mick Jagger, late night confidant of Bob Dylan, pal of Janis Joplin, discoverer of the Grateful Dead, the Jefferson Airplane and Carlos Santana.

Whether you think you know all the details of Graham’s life and career, or know little, you will be dazzled by a mammoth and wildly pleasing new exhibit about his rich life, The Rock & Roll World of Impresario Bill Graham at the New York Historical Society (running February 14-August 23).

The fun starts when you enter and they give you a headset. On the headset, for the one or two hours you spend at the exhibit you listen to some of the greatest rock and roll music ever played. You go from room to room to see, chronologically, Graham’s life as a promoter.

The Grajonca Family, Berlin, ca. 1938

Gelatin silver print

Collection of David and Alex Graham

Did you know that he was not a Bronx native, but was born in Berlin and spirited out of the country as a child in the 1930s by his mother (who would die at Auschwitz) as the Nazis took over, enduring a dangerous train and boat ride from Berlin to New York? Did you know that when he got to Lisbon on that journey, they asked him where he wanted to go to start a new life. He had no answer. “The United States?” an official said. “Yeah, sure,” he said and shrugged his shoulders. Thus was the legend born.

Graham’s love of music and promotion intrigued NYHS CEO Louise Mirrer, but so did his childhood. “Few know about Graham’s immigrant background and New York roots. We are proud to collaborate with our colleagues at the Skirball Cultural Center to present this exhibition in New York – Graham’s first American hometown—and to highlight his local experience. His rock and roll life was a pop cultural version of the American Dream,” she said.

That dream got started when he was the young manager for a street Mime Show. The performers got arrested and Graham staged a concert to raise bail. That was the beginning of a 40 years’ music career that ended suddenly when he died in a freak helicopter crash at the age of 60.

Graham started relatively small; tickets to one of his theaters the, Fillmore East, went for just $3.50 in 1970. In the late ‘60s, you could buy a Sunday afternoon show ticket at the Fillmore West in San Francisco for $1 and get to see the Grateful Dead, AND the Jefferson Airplane AND Carlos Santana. The enterprise grew, however. Graham put up 5,000 of those now-famous wild psychedelic posters in each city where he promoted a show and told the storekeepers that displayed the posters to keep them. The walls of the exhibit are covered with these posters featuring performers and friends such as Janis Joplin, Gracie Slick, Mick Jagger and the Rolling Stones, Etta James. Lenny Bruce, the Grateful Dead, Carlos Santana and Sam the Sham and the Pharoahs. Original copies of some of those posters today area worth several thousand dollars.

Sections of the exhibit tell the story of the Fillmore Auditoriums, East and West, and their short but eventful lives from 1968 to 1971, and of the Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco.

Visitors then pass through rooms telling the story of the huge, 50,000 seat arenas and upscale venues Graham booked for later shows. When Graham was looking for a theater to house a Grateful Dead concert in the 1970s, he turned down his own Fillmore, the Beacon, and Madison Square Garden to put the Dead onstage at Lincoln Center’s swanky, blue-blood Metropolitan Opera House (they sold out, quickly).

Baron Wolman

B.B. King backstage at Winterland Auditorium, San Francisco, December 8, 1967

Gelatin silver print

Iconic Images/Baron Wolman

Graham’s social activism is also represented. Visitors can learn of a show he staged to raise money for poor children’s school lunches in California, which drew 50,000 music fans, notably Willie Mays and Marlon Brando. Graham’s concerts also introduced black blues and R&B musicians like Etta James to young white fans of rock groups they had influenced. Once, B.B. King came to him and said he saw a “bunch of long haired white people” on the ticket line. ” I think they booked us in the wrong place,” he said.

There is social relevance, such as Graham’s campaign to stop Ronald Reagan from visiting a cemetery in Germany where Nazi soldiers were buried and touching stories such as the hundreds of letters he was sent upon the closing of one of his venues. The exhibit also showcases Graham’s personal friendships with musicians. Sometimes these friendships were tested by business. Graham described his time managing the Grateful Dead and the Jefferson Airplane as “the longest year of my life.” There are delicious personal stories, such as his relationship to Bob Dylan. “We heard that Dylan wanted absolute quiet around him all day on the day of a show, so I ordered everybody in the theater not to talk to him. Later at night he comes to my office and says ‘why is nobody talking to me?’

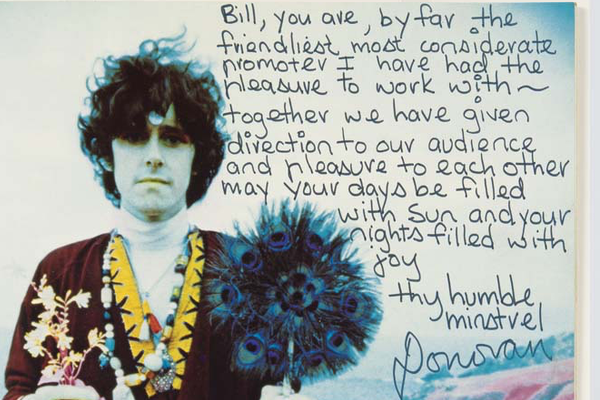

Note from Donovan to Bill Graham, San Francisco, November 1967

Offset print with inscribed ink

Collection of David and Alex Graham

Photo by Robert Wedemeyer

The exhibit contains a wealth of visual and physical artifacts, including stage costumes and a dozen guitars played by musicians in Graham’s orbit. And there are walls full of the famous wildly colored psychedelic posters with all the writing that nobody could understand. “The only thing anybody is going to understand in that poster is the asterisk,” Graham complained to one artist, who, of course paid no attention to him.

Gibson Guitar Corporation 1959

Cherry Sunburst Gibson Les Paul played by Duane Allman of the Allman Brothers Band

during live concert recording at Fillmore East; recorded: March 12–13, 1971

Collection of Galadrielle Allman

Photo by Robert Wedemeyer

Graham was a gregarious, flamboyant man. Actor Peter Coyote said he “was a cross between Mother Theresa and Al Capone.” The promoter always knew that in the rock music world he was working with oddballs. “I always felt that someone had to relate to reality. That someone was me.”

Ken Friedman

Bill Graham between takes during the filming of “A ’60s Reunion with Bill Graham: A Night at the Fillmore,”

Fillmore Auditorium, San Francisco, 1986

Courtesy of Ken Friedman

And he created a marvelous reality for tens of millions of music fans.