Filmmaking, Reality and Fact: How Documentaries Shape Americans' Ideas of Truth

Documentaries—screened, broadcast, and streamed—are more appreciated and influential today than ever before. It’s been said we live in a Golden Age of nonfiction filmmaking. At the same time, media phenomena like “alternative facts” and “fake news” lead some to suggest we live in a “post-truth” era. It’s a major challenge for viewers trying to gain an understanding of contemporary politics, and for those who study America’s past.

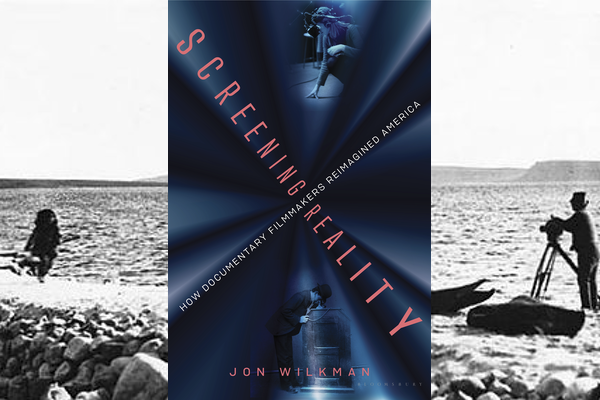

How did we get here? Given that a sizable percentage of Americans get their sense of history through television documentaries, the history of nonfiction filmmaking offers insights. How documentary filmmakers struggled to discover and convey a sense of the real world—succeeding, failing, and compromising along the way—provides a basis for understanding and appreciating the difficulties and importance of representing and determining evidential truth in times where facts are discounted, distorted, or ignored.

Since the first movies in the 1890s, nonfiction filmmakers were driven by curiosity about the real world and changing times—and shaped by interactions with their audiences. Three documentaries focused on families mark changes in both filmmaking techniques and philosophical arguments about how film and television have represented reality during the past one hundred years.

By 1922, the first Dream Factories of Hollywood dominated international movie production, but a less-than-glamorous story about an Inuit family of seal hunters in the Canadian arctic was a surprise box office hit. Shot on location without trained actors, Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North is considered the first documentary film narrative. With moments of drama, suspense, humor, and poignancy—unlike previous travelogues—Flaherty mostly portrays Inuit people as complete human beings, not primitive sources of detached curiosity for his largely white audience, many with attitudes of racial superiority.

Yet, as “realistic” as it appeared (and sought to appear), the truth of Nanook was affected, at least partly, by the filming process. Since the heavy hand-cranked silent cameras of the day limited Flaherty’s ability to respond spontaneously to changing action, he staged much of what he shot. Without the capability to record sound, narrative information and context are provided by title cards.

At a time when distinctions between fiction and nonfiction films were yet to be defined, Flaherty still “cast” his characters: his “star” is a respected seal hunter. Not known as Nanook (Bear), his real name (Allakariallak) would be unpronounceable to English-speakers. The woman who plays Nanook’s wife, “Nyla” (Smiling One), isn’t his actual spouse, but chosen for her beauty.

Notwithstanding these creative licenses, Flaherty intended to act as a cultural preservationist. He aimed to convey a sense of the Inuit as they lived before the influence of the white man. Even though modern academic anthropologists disdain this as “salvage anthropology”—an approach that ignores native people as they are to convey an idealist vision of the past—Flaherty wasn’t making a deliberate attempt to deceive. Despite creative liberties, Inuit life as portrayed in Nanook represents the reality of a forbidding arctic environment where starvation was a true threat to survival. Facing criticism, Flaherty openly admitted, “sometimes you have to lie to tell the truth.”

The idea that small facts can be sacrificed in service to larger truth remained a cornerstone of the craft of documentary film even as modern technology made it possible to record events without more obtrusive staging.

During the 1960s, the invention of light, portable cameras, more sensitive film stock, and easily synchronized sound lifted many of the restraints that had hindered Flaherty. The result was cinéma vérité, a new style and philosophy of nonfiction moviemaking that transformed portrayals of reality on film.

Vérité pioneers like Bob Drew, Ricky Leacock, Al and David Maysles, D.A Pennebaker, and Fred Wiseman sought to capture experience and environment, to give viewers a sense of “being there,” not necessarily to communicate factual information. They vehemently objected to authoritative narration, interviews, and the emotional guidance provided by a separate musical soundtrack. They wanted the audience to be actively involved in evaluating and determining the truth of what was shown, not to be told how to interpret what they were seeing.

Building on the cinéma vérité tradition, the 1973 PBS/WNET series An American Family closely observed the lives of the upper middle-class Loud family of Santa Barbara, California. While previous vérité films, like Drew and Leacock’s Primary, focused on the 1960 Democratic presidential race, suggested a new kind of journalism, An American Family producer Craig Gilbert saw his project in terms of a sociological study. The series was recorded by a husband-and-wife camera and sound team, Alan and Susan Raymond, who virtually lived with the Louds during filming. Despite early sociological intentions, during the editing process, the twelve-part series morphed into a kind of real-life soap opera, with portents of reality TV to come.

As it turned out, along with familiar upper-middle-class activities, life with the Louds unexpectedly included adultery, frequent shots of vodka, and the uninhibited lifestyle of a son, Lance, who was proudly gay at a time when openly gay characters were missing from television and movies. He attracted critical mockery, but later proved to be an example of changing attitudes in the decades to come. As film scholar Jeffrey Ruoff wrote: “Lance Loud didn’t come out on American TV, American television came out of the closet through An American Family.”

As An American Family unfolded, the normally sedate public television audience was divided between fascination and disdain. For many viewers, although the Louds weren’t scripted actors, it was easy to see them less as real people and more like performers playing themselves. The result was a new kind of celebrity and questions that added to doubts about the veracity of screened reality. Did the filmmaking process affect the truth it purported to capture?

Even with these questions, An American Family offers valuable, if filtered, historical evidence, not only about family life in the 1970s, but also the evolution of portrayals of the real world on film and television. Sadly, the outtakes of a popular TV show aren’t often considered serious source material for future study. Most of the three hundred hours of original footage shot by Alan and Susan Raymond was destroyed during a WNET housekeeping session.

If cinéma vérité purists scorn traditional documentary approaches like narration and interviews, found on television since the 1950s—Ken Burns, perhaps the best known and successful contemporary American historical documentarians, is proudly old-fashioned. Burns’s 2014 seven-part, fourteen-hour PBS family portrait The Roosevelts: An Intimate History engagingly traces the intertwined lives of Theodore, Franklin, and Eleanor, based on deep and careful archival research, informative narration by longtime Burns collaborator Geoffrey Ward, and the on-camera guidance of interviews with authority figures and eyewitnesses.

As an evidential historian, Burns benefits from the evolution of nonfiction filmmaking genres between 1920 and 1950, especially newsreels. Teddy Roosevelt wasn’t the first president to appear on film. That was William McKinley in 1896. But TR’s physically flamboyant speaking style made him a compelling “picture man” on silent movie screens.

Sound movies and radio were boons for FDR and Eleanor, providing a vivid sense of who they were in “real life” as well as the world they inhabited—impressions that are harder for print chroniclers to convey. Yet even though contemporary documentarians may access a wealth of facts and engaging archival imagery, questions about how documentaries are made, dating from the days of Nanook, continue, perhaps inevitably, to generate questions about truth on film.

Like his fiction filmmaking counterparts, Ken Burns considers himself a storyteller, “an historian of emotions,” emotions being “the glue of history.” Most viewers found The Roosevelts moving as well as informative. However, fairly or not, a mutual sense of filmmakers and audiences that movies are an emotional medium has long been a burden for nonfiction filmmakers with informative intentions. Despite, or perhaps because of, Burns’ popular success, many academic historians are suspicious of film, considering it a source of impressions and feelings rather than the purported intellectual depth and rigor of the printed word.

Notably, Burns has been criticized for a tendency to view historical stories like the lives of the Roosevelts, and his most lauded effort, The Civil War, in terms of a series of trials that ultimately lead to an uplifting triumph over adversity—a narrative arc found in fiction. Although Burns doesn’t ignore social and political injustices, especially concerning race, as a skilled popular historian he doesn’t dwell on unfinished business that could disturb or challenge viewers who look to historical documentaries to provide a sense of closure.

Compensating for this, “open wounds” from the more recent past are often the subject of less-reassuring documentaries like The Central Park Five. An uncharacteristic Burns film, made in collaboration with his daughter Sarah and her husband David McMahon, The Central Park Five investigated the unjust conviction of a group of young African American and Latino teenagers accused of a brutal (and sensationally-reported) rape.

The nonfiction film history I’ve sketched reveals the persistent limitations and compromises of documentary film as well as the medium’s expressive strengths. Just as academic historians bicker over differences of interpretation and the importance of archival minutia, without dismissing the idea of truth itself, serious documentarians are just as committed to reflecting an honest sense of the real world.

This is especially vital during a moment in society when people may toggle between believing what is staged and edited, cynically rejecting everything as fake, or selectively embracing evidence that affirms their beliefs. Polarized audiences can be tempted to dismiss documentaries as just another a kind of entertainment—no more true than fiction films.

Such attitudes are encouraged by the reality TV presidency of Donald Trump, whose administration is known for a dramatized attitude toward the real world, an entertainer’s ability to appeal to emotions, tweets that offer diverting plot twists, and attention-grabbing behavior that delights fans and outrages the less enamored.

If this weren’t enough, there could be more uncertainty ahead. Technology has transformed the possibilities and supported new forms of nonfiction storytelling and will affect traditional historians as well. The emerging realm of “deepfake” imagery threatens to manipulate real images beyond detection, and artificial intelligence can target viewers with the stories they prefer to see, true or not.

Like all nonfiction, documentary films have always depended on credibility, even when the building blocks of moving images have been staged, selectively edited, or chosen above others for reasons of narrative. Of course, print historians face similar challenges in constructing narratives that marry facts with interpretations, rather than simply assembling encyclopedic lists of dates and names. Unlike a documentarian, a fiction filmmaker can have a flop and move on. For a creator of nonfiction films, losing audience trust is catastrophic.

Viewers can lose out, too. If they make choices about what they believe based on entertainment appeal or personal preference rather than thoughtful evaluation, even a Golden Age of documentaries can become counterfeit. American democracy—and an accurate appreciation of our past—will be the worse for it.