Trump Talks Like President Roosevelt But Acts Like President Hoover

When the Great Depression threatened the well-being of millions of Americans, President Franklin D. Roosevelt acted swiftly. In his administration’s first “hundred days” new initiatives restored public confidence and set the nation on a road to recovery. In contrast, President Donald Trump has reacted slowly and inadequately to the mounting threat from COVID-19. Trump invoked language that resembled Roosevelt’s, saying he would deal with the pandemic as a “wartime president.” President Trump claimed bold leadership in a “medical war,” but he has not backed words with strong action. Like Herbert Hoover, the troubled president who preceded Roosevelt, Trump has been reluctant to exercise federal power in a crisis.

At first glance the two situations seem distinct. Roosevelt faced a huge economic challenge, and Trump is dealing with a threat to public health. Yet both crises involve economics. If Trump does not respond effectively to COVID-19, business shutdowns may produce a depression. Economists worry that U.S. unemployment could reach 30% or more later this year if the epidemic’s growth is not checked soon.

During the Great Depression, Herbert Hoover supported some initiatives by the federal government, but he opposed extensive federal intervention. Hoover favored voluntarism and individual efforts. When markets crashed, he asked corporate leaders to maintain production and employment. Later, Hoover supported incremental measures, but those programs failed to arrest the deepening crisis. Hoover’s reputation was in tatters in the last days of his administration.

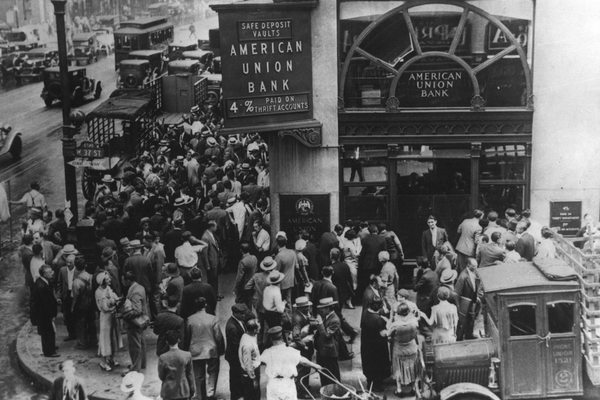

When FDR took the oath of office on March 4, 1933, unemployment approached 25% and the financial system of the United States was near collapse. Roosevelt’s inaugural address excited hope with a message that “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” Roosevelt explained how he intended to combat the depression. He asked Congress for “broad executive power to wage war against the emergency, as great as the power that would be given to me if we were in fact invaded by a foreign foe.” During the next hundred days, the New Deal initiated thirteen major legislative programs.

Roosevelt and the Congress rescued troubled banks, provided jobs for millions of unemployed Americans, raised depressed farm prices, and created the TVA, which stimulated the southern economy. Broad-based recovery took years, but the New Deal’s actions quickly lifted public confidence. Days after Roosevelt’s inauguration, citizens that had hoarded cash returned money to the banks. The stock market surged with its largest one-day increase in history. In the 1936 presidential election, voters gave Roosevelt a second presidential term by a 523-8 electoral count.

Mimicking Roosevelt's language, Trump announced he was commanding of a “big war” against the coronavirus. Trump congratulated his administration for mobilizing resources. In televised news conferences he described enormous progress securing test kits, masks and gowns for health care workers. When journalists cited reports about huge shortages, Trump offered vague or dismissive responses.

Like Herbert Hoover, Trump has been relying considerably on voluntary efforts. He praised the CEOs of major corporations for promising aid in the emergency. Trump prefers a free market approach. He opposes strong federal intervention in business affairs, including efforts to invoke the Defense Production Act so that Washington can direct manufacturers to produce test kits, clothing for doctors and nurses, and ventilators for patients.

Critics disagree. They point out that temporary federal coordination does not represent an assault on free enterprise. It is an emergency measure. State governments are presently competing against each other in desperate efforts to obtain supplies. If officials in Washington provide direction, they can prevent price-gouging and facilitate the purchase of vital equipment.

Ever since the covid-19 threat became evident, President Trump has been hesitant about dealing forcefully with the dangers. Rather than create a robust central command in Washington to coordinate the medical response, Trump has practiced a version of laissez-faire. He left action in the crisis largely to state governments, and local hospitals. Then, in the manner of Herbert Hoover, Trump slowly changed course. After infections and deaths soared, he agreed to put new federal measures in place, including recommendations that most citizens stay at home. Nevertheless, Trump refused to use his presidential authority broadly to get ahead of a crisis, as Franklin D. Roosevelt did.

President Trump received numerous alerts about the pandemic, but he was slow to react. U.S. intelligence agents warned in January and February 2020 that the coronavirus could devastate American society. Trump and members of his administration saw their reports. Senior officials urged President Trump to act immediately, but as one of them noted, “they just couldn’t get [the president] to do anything about it.” In February Trump played down the seriousness of the threat. On February 10 he predicted the virus would disappear in the April heat, and on February 24 he claimed the problem was “very much under control in the USA.”

The threat that worried intelligence officials became abundantly evident by mid-March, and still the president hesitated. Doctors and nurses complained about huge shortages of protective gear. Trump referred the matter to state governors, saying, “we’re not a shipping clerk.” In the manner of Herbert Hoover, he resisted calls for aggressive leadership from Washington.

Absent direction from the White House, the medical response lacked organization and guidance. There were huge differences in the way states, communities and businesses dealt with the pandemic. In March health officials warned emphatically that cruise travel was dangerous, yet ships filled with thousands of passengers, including many vulnerable senior citizens, were still at sea. San Francisco, New York, and other cities locked down while thousands of young people celebrated Spring Break on Florida’s beaches.

Lack of central direction also undermined work by medical researchers and drug companies to develop effective treatments for covid-19, including a vaccine. The Washington Post reported on April 15 that the “massive effort is disorganized and scattershot,” damaging prospects for success. Because there was no centralized national strategy, research efforts often overlapped. Investigators were not clear about how to collect or share data. “It’s a cacophony – it’s not an orchestra,” complained Dr. Derek Angus of the University of Pittsburgh’s School of Medicine. “There is no conductor.” Biomedical research is paramount for combating the pandemic and rescuing the economy. Yet Washington has not appointed a principal coordinator in the manner that J. Robert Oppenheimer directed research on atomic weaponry in World War II.

When scientists, including Albert Einstein, warned Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1939 that German researchers might be developing nuclear weapons, the president acted. He told the individual who presented the information, “what you are after is to see that the Nazis don’t blow us up.” An advisory committee quickly brought together top scientists to begin planning. After the United States entered the war in December 1941, President Roosevelt found enough money to shift the program into high gear. With $2 billion and 120,000 workers, the secret Manhattan Project made an extraordinary technological breakthrough. J. Robert Oppenheimer, a brilliant theoretical physicist, headed the weapons laboratory that succeeded in the producing atomic bombs.

Research on the coronavirus needs a program that resembles the Manhattan Project. Medical scientists in the U.S. and abroad can benefit from a well-funded and well-managed program that is coordinated by a talented professional like Oppenheimer. Unfortunately, like so many current efforts to deal with the crisis, work has been fragmented. As Dr. Angus noted, it is difficult to make fine music when there is no conductor.

In one notable respect, however, President Trump has attempted to command from Washington. When governors from several East coast and West coast states announced plans to coordinate decision-making about reopening their economies, Trump objected. He declared, “When somebody is president of the United States, the authority is total.” Scholars, business leaders, and members of Congress challenged that interpretation. They pointed out that separation of powers in the federal system allows governors responsibility in these matters. Some critics pointed to a glaring contradiction in Trump’s position. For months, the president had insisted that businesses, hospitals, and local officials were primarily responsible for dealing with the pandemic. But when governors tried to protect citizens from the White House’s attempts to end social distancing before broad-based testing was in place, Trump wanted to assert executive power.

The contrast is striking between President Trump’s clumsy, haphazard and hesitant response to the health crisis and Franklin D. Roosevelt’s all-hands-on-deck approach to the Great Depression. FDR’s New Deal cooperated with state and local governments when administering programs, but leadership and planning came largely from Washington. President Roosevelt understood that the federal government needed to assume primary responsibility for directing responses in a time of extraordinary difficulties. FDR did not simply talk about waging “war against the emergency.” He mobilized the nation for combat.

Programs initiated in Washington during FDR’s first hundred days did not solve all problems of the Great Depression. Nor can immediate and well-planned mobilization by the current administration stop covid-19 in its tracks. But Roosevelt’s example of broad-based action shows that strong presidential leadership can improve conditions quickly and lift the spirits of an anxious people. Presently, Americans need a true “wartime president.”