History Should Have Told Us not to Believe the Quinine Drug Hype

Editor's note: this article was submitted and accepted for publication prior to recent reporting of a Veterans Administration observational study of patient outcomes (not a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial) which observed higher death rates among VA patients treated with hydroxychloroquine than those not treated with the drug. Also subsequent to HNN's decision to publish, the FDA has advised against the use of hydroxychloroquine to treat COVID-19 outside of hospital or controlled clinical trial settings.

Will hydroxychloroquine save us from this pandemic? Probably not. Big pharmaceutical companies have long over-promised the efficacy of their antimalarial drugs. This started a century ago, when European antimalarial producers began aggressively touting the curative effects of quinine on all manner of disease. Yes, antimalarials work wonders against malaria, but not against much else. This history suggests that political and economic reasons for pushing these antimalarials upon a global disease are again at work.

From the earliest discovery of an effective remedy for malaria in the 17th century, physicians have held out hope that antimalarials could cure a wide range of illnesses, from common ailments to serious diseases. The main group of antimarial drugs, first known as Peruvian Bark, later chemically isolated as quinine, and now including synthetic analogs of quinine such as chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, were the world’s first wonder drugs. They really worked, and still do, against malaria, the world’s oldest and deadliest disease. Because the plasmodia that causes malaria existed before modern humans, it spread to all corners of the world, inside migrating humans. And wherever the Anopheles mosquito thrived, it spread malaria from person to person. Today we think of malaria as a tropical disease, but until a century ago, it existed in temperate climates throughout North America, Europe, Africa, Oceania, and Asia. Antimalarials, although not always able to cure the disease, did reduce the high fevers of malaria, and dramatically cut the mortality rate of the disease. In the 19th century, when quinine availability increased and came to be packaged by pharmaceutical companies in oral doses, it was recommended widely as a prophylactic, that is, as a preventative medicine against malaria. For many, it was a real miracle drug, and until the 20th century, one of the very few drugs which lived up to its promise of curing and preventing a global disease.

Given the success of these antimalarials, it is hardly surprising that physicians have reached, time and time again, for this successful group of drugs, in an attempt to cure other diseases, especially those which exhibit a high fever as an early symptom. This was particularly true in the 19th and early 20th century, when there were few other alternative drugs, and the causes and mechanisms of many diseases were not well known. Most doctors had quinine on hand, as malaria was widespread on all continents, and after the 1880s, quinine was cheap and being produced in convenient oral medicines by numerous pharmaceutical companies. There was widespread awareness of antimalarials – for example, many patent medicines contained quinine (or claimed they did). And physicians, when nothing else was known to work, acted in a way we today would still find ethical – little harm might come from giving quinine, and it might work on diseases besides malaria. Medical doctors not only experimented with quinine in their own clinics, but wrote up their perceived success stories, and mailed them to medical journals. Today we would call their data anecdotal. But these dispatches were medical science for the time – long before clinical trials – in which a physician trying a procedure on a small number of patients in his care, and then reporting results, was standard and appropriate. And this led to reports of quinine reducing the symptoms of influenza, yellow fever, and even cancer. To be clear, it never actually did.

Since the development of synthetic analogs to quinine in the 1940s and 1950s, there has continued to be experimentation with antimalarials, and we now know that they have some effectiveness against other diseases, including immune disorders such as lupus. There is today not only much more awareness of how both drugs and diseases work – the link between mosquitoes, the plasmodia organism, and malaria was not established until 1900 – but there are far more wonder-cures which work as advertised against human diseases, notably, antibiotics. But starting with the SARS outbreak, and faced with a coronavirus for which humans have no immunity and on which antibiotics are ineffective, some physicians and scientists experimented with antimalarials. Chloroquine disrupts the life-cycle of the simple organism that causes malaria, and in some experiments, also was toxic to the SARS coronavirus. The miracle of these antimalarials is that in relatively small doses it kills the plasmodia that causes malaria, but does not harm the human host, or not much; in high enough doses, antimalarials, and especially chloroquine, are also toxic to humans.

There is some historical evidence that the number of people who have taken chloroquine and quinine for prolonged periods is much smaller than thought, and that therefore the safeness of these antimalarials has been exaggerated. Nonetheless, in small doses, and taken for short periods of time, it is safe. Perhaps it will have some effectiveness against COVID-19, but a long history of failures of antimalarials to treat other diseases suggests not.

And finally, it’s important to remember that while experimenting with antimalarials can be proper medical practice, the distribution and promotion of antimalarials has been political from the start. What started off as a remedy known to healers in the Andean mountains was appropriated by Jesuit scholars in the 17th century, who dispensed Peruvian Bark to select audiences. In the late 18th century, expertise about the Peruvian Bark was taken over by Enlightenment naturalists, who sought to show that reason and science could conquer both nature and disease.

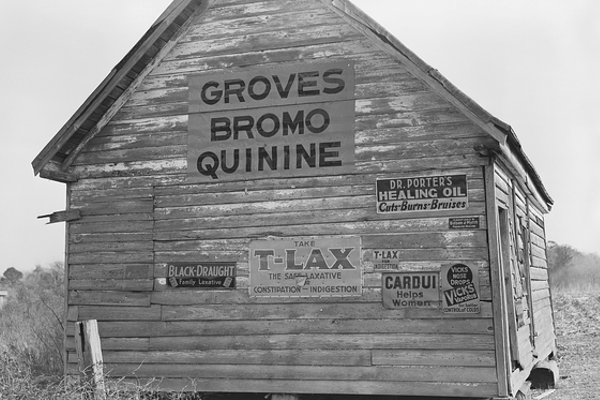

And after 1900, when most of the world’s antimalarials came from 100 plantations in Dutch controlled Indonesia, a cartel of imperial growers and pharmaceutical companies sought not only to increase the price of antimalarials, but to promote its use widely—against malaria, yes, but also against other diseases. The purpose was to sell more quinine, and to remind the world of the importance of the Dutch empire as the provider of indispensable medicine. In the 1920s, the cartel’s sponsored Quinine Institute collected scientific studies about quinine, translated them, and sent them free of charge to public health organizations around the globe. They reported that quinine was effective in treating influenza, pneumonia, heart-disease, hearing-loss, and venereal diseases. Other articles suggested it could act as a dental anesthesia and an abortifacient.

Most of the studies are short, reporting results from treating a few dozen patients. One article from 1923, less than 400 words long, claims that giving patients quinine injections at the onset of pneumonia dramatically lessens their mortality rate. Notwithstanding the enthusiastic promotion of these uses for diseases other than malaria, today these cures have been forgotten, because they are not effective. But the political potency of antimalarials lives on. Physicians and scientists should not be faulted for experimenting with these drugs, but for business leaders and statesmen to overpromise their efficacy is irresponsible.