Youth Crises Past and Present: Learning from the New Deal and Eleanor Roosevelt

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought to mind the Great Depression because of its economic impact—more than 30 people million filed jobless claims between mid-March and this week.

Less appreciated are the parallels on how America’s youth were and are being affected.

The Great Depression wrought a youth crisis of unprecedented proportions—a crisis that threatens to resurface 90 years later.

Fortunately, our 20th-century responses offer guidance, from both President Franklin Roosevelt and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, on how to diminish the damage of the coronavirus.

In the 1930s, children and teens were among the most economically, educationally, and psychologically vulnerable to the ravages of the Depression. The Relief Census of 1933 revealed that 42 per cent of all relief recipients were under 16 years of age, though this age group constituted only 31 per cent of the US population. Surveys of youth unemployment among 16-24 year olds found joblessness at 47 percent in Detroit, 53 percent in Denver, and 57 percent in Newark in 1934-1935. By 1934 some 20,000 rural schools had closed because of plummeting public revenues, and in the 1932-1933 academic year lack of funds caused about 80,000 college students to drop out, the first peacetime year in the 20th century when college enrollments declined.

This youth crisis generated a dynamic response both from the bottom up and the top down in Depression America. From below came a mass student movement, led by young socialists, liberals, and Communists demanding federal student aid, what we would today call work-study jobs, for all needy college and high school students so that none would have to drop out of school because of poverty.

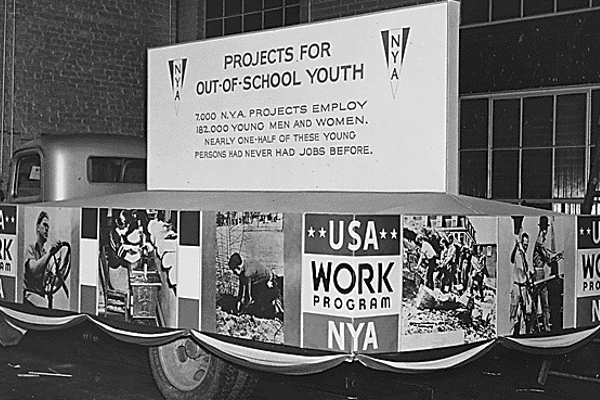

FDR and the New Deal responded to the youth crisis and these demands for aid to hard-hit young people by creating federally sponsored jobs for students first under the Federal Emergency Relief Administration and then through the National Youth Administration (NYA), helping to reverse the decline in high school and college enrollments. New Deal dollars also funded free school lunch programs, teacher salaries in America’s poorest states, and 70 percent of all new school construction between 1933 and 1939.

Beyond this badly needed New Deal economic assistance, low income youth found inspiration in the work First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt did to raise America’s consciousness of the need to keep faith with the younger generation and to do all possible to secure its future.

“I have moments of real terror,” Mrs. Roosevelt explained in 1934, “when I think we may be losing this generation. We have got to bring these young people into the active life of the community and make them feel they are necessary.”

The First Lady served on the NYA board, and often used her daily newspaper columns and weekly radio addresses to advocate more federal aid to the young and to spotlight the progress of New Deal youth programs. All of this, plus Mrs. Roosevelt’s own role as a mother, grandmother, former teacher and school leader made her a magnet for thousands of Depression children and teens who wrote her letters describing their poverty, material and educational needs, and seeking assistance for themselves and their families. These young letter writers were often admiring, even loving towards ER, who they felt cared deeply about them and their plight.

“I’ve often heard how good and kind you were to poor folks, especially children,” wrote a 14 year old Virginia girl in 1934. A midwestern eleven year old, explained in 1935 that she was writing the First Lady because “Mother said Mrs. Roosevelt is just a Godmother to the world …an angle [angel] for doing so much for the poor.”

Though there are today upwards of 30 million Americans suddenly unemployed, schools shut down due to the pandemic, and low income students shut out of remote learning due to lack of access to the internet, one hears little out of Washington about the emerging youth crisis. Where is the plan to address the losses in education, the expanding poverty and the demoralization of youth wrought by the pandemic and the collapse of the American economy? It is time to start demanding a successor to the National Youth Administration to meet the educational and economic needs of students--and to ask who in Washington will carry the torch that Eleanor Roosevelt raised during the Depression decade as the champion of low income youth.