Disruption and Resilience: Lessons from the Ancient History of the 2000s

In the very first episode of Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood in 1967, the puppet character King Friday XIII declared, “Down with the changers – because we don’t want anything to change!” Fred Rogers astutely recognized how difficult it is for many to accept change. It is thrust upon us, unwelcome, and we have to adapt to our new reality. Disruption happens.

This has certainly been the case with the COVID-19 pandemic that erupted in the U.S. in early 2020. It brought on a swift and unexpected recession that threw millions out of work. People have compared this not just to the Great Recession of a decade earlier, but to the Great Depression of the 1930s. Indeed, as I write this in the midst of the crisis, no one knows how long this era of public distancing, mask-wearing and daily death counts will last. We have all had our lives severely disrupted.

We like to believe that we are in control, but control is often a myth. Disruption is always around the corner, and with it comes anxiety, uncertainty, and an unknown future that leads to toilet paper hoarding. When will this public health crisis end? When will life return to normalcy? When will it be safe to gather with friends, or how quickly will the economy rebound once the crisis ends? When is it safe to go on a date, or be intimate, or dine in a restaurant or board an airplane? No one knows.

The pandemic is a huge disruption that will likely last into 2021, with the end hope of deploying a viable vaccine. Millions are unemployed with uncertain prospects of businesses reopening. Schools are canceled for the academic year and children are home, driving their parents bonkers. The entire family has found their lives disrupted.

But I will tell you: this isn’t forever. This is just for now. We will get through this.

How do we know? Because we’ve been through this many times before in our history. Maybe not exactly this, but many other disruptions, and we’ve always managed to come out the other side. True, this is my first pandemic, as it most likely is yours too. History is full of disruption but also catharsis — and we humans have proved resilient.

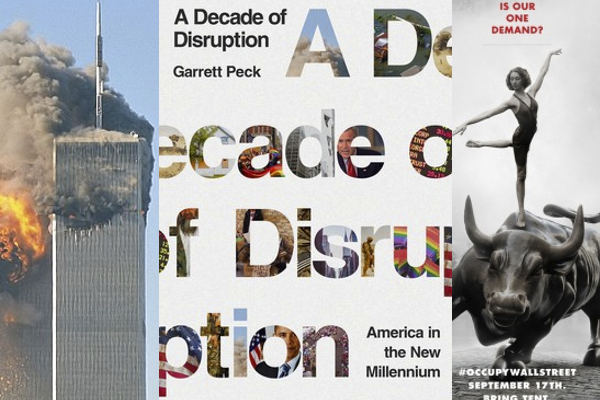

In my latest book, A Decade of Disruption: America in the New Millennium 2000 – 2010, I composed a narrative history of a controversial decade that we all lived through, bookended by two major financial crises: the dot.com meltdown and the Great Recession – and plenty of disruptive events in between. Here we are a decade later with a strong sense of déjà vu. Remember how the nation was glued to our television sets in the days after the September 11 terrorist attacks? It rather feels that way now as the news is full of stories about the coronavirus. Everything changed after 9/11, just as things will be different once this pandemic ends.

The story of our lives is one of disruption but also resilience. 9/11 was enormously disruptive, an event that shaped the first decade and reminded Americans that the world is a complicated and dangerous place. It disproved the post-Cold War notion that history was over (hint: it’s never over). I worked at WorldCom at the time, and witnessed firsthand the meltdown of a once-proud company from simple corporate greed to boost the stock price. The Iraq War, the biggest strategic mistake of the decade, was a self-inflicted wound that damaged our country’s reputation abroad. The Great Recession was a seismic disruption, costing millions of people their homes and a giant, unpopular bailout of the financial sector that planted the seeds for the Tea Party.

We’ve been blessed with the internet, an amazing, resilient tool designed to survive a nuclear war with all of the world’s information (and mis/disinformation as well) right at your fingertips. But how much of our privacy have we yielded by embracing new technologies, as many companies are more than happy to sell our personal data to advertisers?

Digital technology has proved massively disruptive. Amazon steamrolled over the retail market. Google overturned so many business models, and now consumers expect online content to be free. Netflix undermined the movie theater business. Ride sharing companies Lyft and Uber have disrupted the taxi industry. Natural gas and renewables are putting the coal industry out of business. Someone is always building a better mousetrap, rendering your business model obsolete.

And yes, in our own time, President Donald Trump has proved the ultimate disruptor. He is a symptom, but not a cause, of white working-class disaffection after the Great Recession shook out many of the remaining high-paying, low-skill jobs. He tapped into white America’s racial anxiety of a nation becoming demographically ever browner. As I wrote in A Decade of Disruption, Trump “drove a red-hot poker into America’s cultural fissures and fanned the flames, widening an already divided country into hostile camps.”

Trump’s management of the pandemic has been disastrous. He ignored the looming pandemic for a crucial seventy days, actively undermined governors and scientists, endlessly contradicted himself, spewed out nonsense like injecting bleach and disinfectant, set a bad example by refusing to wear a face mask, and stoked tribal divisions. He showed no ability to unite the country behind a common purpose, let alone empathize with people’s suffering. There is no Harry Truman “the buck stops here” sense of responsibility with Trump, who simply refuses to lead. He is a terrible crisis manager who increasingly resembles a flailing Herbert Hoover during the Great Depression. Trump’s ineptness in the pandemic overshadows George W. Bush’s sluggish response to 2005’s Hurricane Katrina by a mile.

We are reminded how senseless tribalism is in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. The coronavirus does not discriminate between old and young, rural and urban, Democrat and Republican. But is the pandemic a shared national experience like World War II or 9/11? Yes and no. We shared in isolation, and we shared in social media, but the coronavirus affected different parts of the country differently. Some chafed at the restrictions; others wanted to reopen the businesses and face the dire consequences. Still others thought it was no worse than the flu.

And yet.

Faced with the Darwinian choice of allowing an estimated 2.2 million people to die – largely the elderly and those with underlying health conditions – or save the economy, Americans chose collectively to sacrifice by staying home so that others might live. We rallied around the idea that we had to protect others. We demonstrated incredible and unexpected solidarity as the pandemic became part of our shared national experience. And we watched a lot of Netflix and learned how to create a sourdough starter and made ice cream in a Mason jar.

With the pandemic, we essentially put our economy into a medically-induced coma to defeat this nasty pathogen. We hope the patient can spring back once revived. A huge downside is that many of the most vulnerable are suffering the most – those in the service economy. These are people with low wages who tend to live paycheck-to-paycheck.

Knowledge workers have the luxury of working from home, even if their kids are a major distraction. But if a service economy employee can’t get to work, they don’t get paid, simple as that. Being a full-time author and tour guide, I learned firsthand that there is no safety net in the gig economy. In March 2020 – the start of the busy season for tour guides – the hospitality industry simply eviscerated as the pandemic gained steam. Nearly 41 million people were laid off in the first ten weeks as the health emergency fueled an economic crisis unprecedented in our nation’s history.

The coronavirus has disproportionately impacted people of color, where poverty and race intersect to produce asthma, diabetes, heart and lung ailments, and hypertension – all underlying health conditions that the pathogen has exploited. We have seen far too many of our fellow citizens die from COVID. People of color are also more likely to be “essential workers” in food delivery, grocery stores, hospitals, and nursing homes. They stand in harm’s way to protect the rest of us.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt stated in his inauguration address on March 4, 1933, in the worst days of the Great Depression, when a quarter of the American workforce was unemployed: “If I read the temper of our people correctly, we now realize as we have never realized before our interdependence on each other; that we cannot merely take but we must give as well.” We are bound by community.

Just as the Great Depression changed our country – and the role of the federal government – the pandemic will do the same. The coronavirus has exposed how fragile our social compact is. Inequality is soaring to where it was in the 1920s. For decades, conservatives have disparaged and undermined the government, and we see this come home to roost in the pandemic, where the federal response has been a patchwork. We have no national plan to address the coronavirus, only denial, wishful thinking, and vigorous hand-washing.

How do we rebuild the social compact that joins all Americans together after this pandemic? How do we renew trust in government, which we sorely need? How do we reduce inequality and improve economic mobility for the many who are stuck?

In his 1651 masterpiece The Leviathan, published at the end of the decade-long English Civil War, political philosopher Thomas Hobbes warned that without intermediating institutions such as a reliable government, humanity would have “no arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

But what I have witnessed during this pandemic doesn’t resemble a Hobbesian outcome, but rather extraordinary resilience and solidarity among Americans. People are pulling together to help others. Strangers are speaking from a distance, asking how they are doing. Neighbors are running errands for one another, risking their health to protect those who are most at risk. It may not feel like much, but it makes a difference as we weather this storm together.

This pandemic will end, I promise. We will get through it, like hundreds of crises our nation has faced before. We have all had our lives disrupted, and we must remain resilient. Just don’t expect things to be the same afterward. A catharsis is coming.

And please: vote this November like your country depends on it.