Trump Made it Manifestly Clear: The Discussion of National Destiny is Ongoing

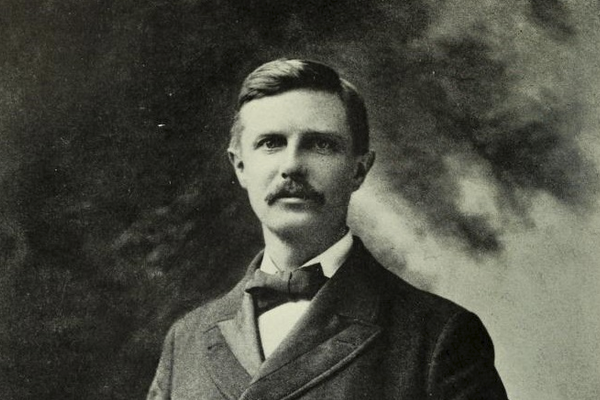

Frederick Jackson Turner, 1902

Before there was a #BLM, before there was a Donald Trump, before there was an American Century, there was a frontier. Not a metaphorical frontier, like space or the edge of human knowledge, but an actual frontier. It marked the Western edge of civilization in America, and beyond it lay seemingly endless plains and mountains – empty of everything except the treasure and adventure which waited for the man (and it was, of course, always a man) who was brave enough to go out and take it with nothing but his own two hands. The taking of that theretofore unseen land and its treasures, from the Appalachians to the Pacific coast, was more than an opportunity for a young nation – it was an almost sacred duty for every young man worthy of the name. It was a fearful dream, a terrible hope, and a beautiful promise all rolled into one package; it was a birthright, an obligation, and an inevitability – it was a destiny.

But, more than any of that, it was a blood-soaked lie.

The frontier existed, and so did the men and women who lived on its edge and ventured beyond it. The treasures were real too, but the land was not empty. Peoples like the Sioux, the Apache, the Ute, and many others were already there, and they had been living in that ‘empty’ land for longer than the ancestors of the European-American settlers had lived outside of caves. Over more than two centuries, the American frontier changed in size and location, but, by the time Frederick Jackson Turner picked up his pen in 1893, the myth of a nation built upon an empty land, and its own manifest destiny, had crystallized. If that myth were still held as gospel truth, it would be no surprise to read the celebration of manifest destiny that the White House released on July 6. One and a quarter centuries ago, that exact message would have seemed no more morally repugnant, socially out-of-step, or historically ignorant than Turner’s Frontier Thesis. The only problem is, one and a quarter centuries have passed since that was true.

In opening years of the 20th century, America appeared poised to follow the examples of expansionist European powers into a new imperialist age. Theodore Roosevelt’s presidential tenure saw, among other things: the consolidation of American control of several former Spanish colonial possessions, the engineering of Panamanian independence to facilitate the construction of a U.S.-operated canal, the declaration of American naval superiority in the form of the world tour of the Great White Fleet, and the continuation of the series of violent suppressions of native Americans (which would continue until the end of the ‘Indian Wars’ in 1924) and African-Americans in both the urban North and the rural South. While the Turnerian view of the frontier was not entirely met without dissent within the American historical establishment, it would hold sway for much of the first half of the century.

In a book or a movie, this might be the point when a single heroic soul would be called upon to make things right. The problem is that climbing out of the nadir of American race relations and persuading the country to acknowledge the ocean of blood and tears that allowed the United States to grow into the powerhouse which dominated Henry Luce’s American century was too great a task for any one person. The glory of our past is that there were many such heroes, who, together, were up to the task. Out of an abundance of heroes, America was lifted out of the nadir and toward a dream of full freedom. A long line of people like Ida B. Wells, John Hope Franklin, Anna Julia Cooper, Eleanor Roosevelt, Bayard Rustin, Lyndon Johnson, Kenneth Stampp, and Francis Jennings changed the way Americans thought of each other, and how we continue to think about our common history. That is why it is so very shocking and incredibly offensive to even imagine an American president who, after those many lifetimes of desperate struggling to overcome that narrative, could be capable of glorifying the idea of manifest destiny. But, despite all of the work of those who came before us, that is exactly what the Trump administration has done this week.

As we enter the third decade of the 21st century, we appear to be facing many of the same problems our nation was forced to confront in the first decade of the 20th century. The murders of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and many other Americans at the hands of trusted authorities who are too corrupt, too callous, or simply too racist to care would have been all too familiar to Ida B. Wells. That’s why America desperately needs a 21st century Ida, an Anna, a Lyndon, and a Bayard to see our situation for what it is and to choose to do the hard work of building a better country for everyone – in fact, we need thousands of them! As a historian, I am used to telling stories that do not have happy endings, and, for now at least, this is no exception. We can take heart that our country and our discipline have come a long way from the nadir and Frederick Jackson Turner. Somewhere between Teddy Roosevelt and Colin Kaepernick, we have managed to pick up a few yards as Americans and as American Historians. We are, perhaps, justified in taking a small measure of pride in the work that has already been done and the distance that has already been run, but we have miles, perhaps even marathons, that are still left ahead of us. If we still needed proof of that, the president just made it manifestly clear. Let’s get to work.