The History of the Boycott Shows a Real Cancel Culture

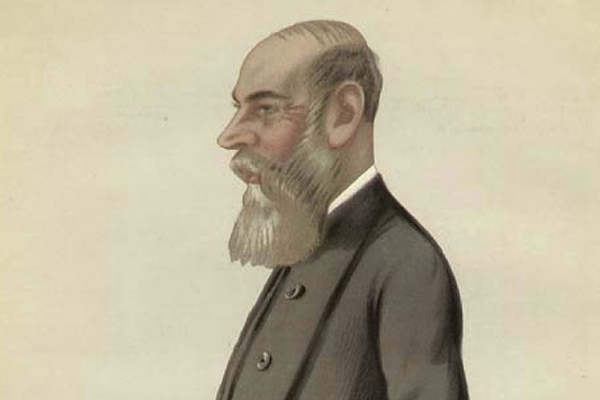

Charles Boycott caricatured in Vanity Fair, 1881.

J.K. Rowling, Margaret Atwood, Salman Rushdie, and Noam Chomsky are among dozens of writers, artists and academics who signed a July 7 letter in Harper’s Magazine that warned of growing “censoriousness” in our culture. They described this as “an intolerance of opposing views, a vogue for public shaming and ostracism, and the tendency to dissolve complex policy issues in a blinding moral certainty.”

The writers didn’t use the term “cancel culture,” which Wikipedia describes as “a form of public shaming in which internet users are harassed, mocked, and bullied.” But that’s what they are talking about.

While cancel culture deploys modern technology, it is hardly a new tactic. It most famously dates to 1880 in the west of Ireland, when English land agent Charles Boycott's last name became a verb for the practice.

Agrarian activists targeted the County Mayo estate that Boycott managed in the early stages of the Irish Land War as tenants agitated for more influence over their rents and lease terms. Seasonal workers were pressured to withhold their labor from Boycott at harvest time, and nearby shopkeepers were menaced to avoid doing business with him.

The boycott was born.

Irish parliamentarian Charles Stewart Parnell recommended the tactic weeks earlier during a speech at Ennis, County Clare, about 80 miles to the south of Mayo.

“When a man takes a farm from which another has been evicted, you must shun him on the roadside when you meet him – you must shun him in the streets of the town – you must shun him in the shop – you must shun him on the fair green and in the market place, and even in the place of worship, by leaving him alone, by putting him in moral Coventry, by isolating him from the rest of the country, as if he were the leper of old – you must show him your detestation of the crime he committed.”

(Parnell faced his own “canceling” in 1890 when his longstanding extramarital affair with Katherine O’Shea was revealed and created a public scandal.)

Agrarian activist Michael Davitt used the image of a leper to describe those who did not support the Irish Land League’s fight against the landlord system. Any such person was “a cowardly, slimy renegade, a man who should be looked upon as a social leper, contact with whom should be considered a stigma and a reproach,” Davitt said.

No matter how righteous the cause of landlord-tenant reform, the tactics were taken to brutal extremes, including murder. In 1888, boycotted farmer James Fitzmaurice was shot at point blank in front of his young adult daughter, Nora, as they steered a horse cart to an agricultural fair in County Kerry.

Later, at a special commission exploring the land unrest in Ireland, his daughter testified that after the attack five separate travelers passed on the road because they recognized her as belonging to a boycotted family. Only one stopped, coldly noted that her father was “not dead yet,” then proceeded without helping.

Two men were convicted of the murder and hanged. More typically, intimidated or obstinate witnesses refused to testify against the perpetrators of murders and assaults against their boycotted neighbors.

Threatening notices or placards -- the 19th century print equivalent of social media posts -- appeared in town squares and at rural crossroads, naming names and often including crude drawings of coffins or pistols.

Social ostracism was hardly new to Ireland, though. Even before the land war, some Irish considered it better to starve to death than to consort with the other side.

In his 1852 book Fortnight in Ireland, English aristocrat Sir Francis Head described the reaction to attempted religious conversions tied to accepting food in the wake of the Great Famine. “Any Roman Catholic who listens to a Protestant clergyman, or to a Scripture reader, is denounced as a marked man, and people are forbidden to have any dealings with him in trade or business, to sell him food or buy it from him,” he wrote.

In his seminal work Social Origins of the Irish Land War, historian Samuel Clark said of boycotting: “The practice was obviously not invented by Irish farmers in 1880. For centuries, in all parts of the world, it had been employed by active combinations [social groups] for a variety of purposes.”

Yet Clark continued: “What was novel … was … the spread and development of this type of collective action on a scale so enormous that the coining of a new term was necessary. Boycotting was becoming the most awesome feature of the [Irish land] agitation.”

Cyberbullying is unpleasant, to be sure. But it is hardly the same as being beaten or murdered. Authors, academics, musicians, and others bothered by their work being “cancelled” might consider the original boycott for some needed perspective. Or perhaps they should leave the rough and tumble of the marketplace of ideas.