John Oliver Dunked on Joy Behar over George Washington's Slaveowning, but Didn't Do the Reading Himself

Reviewed: “The Only Unavoidable Subject of Regret”: George Washington, Slavery, and the Enslaved Community at Mount Vernon by Mary Thompson.

Comedian John Oliver recently joined the chorus of people denouncing America’s founding fathers as unworthy of admiration because of their connection to slavery. This time, the target was George Washington.

Commenting on an episode of ABC’s morning talk show The View where Joy Behar said that statues of Washington deserved to stay up not only because he’d won the Revolution but also because he’d freed his slaves, Oliver sided with a show guest who said that Behar was wrong, and that Washington was actually a “horrible slaveowner.”

White people like Behar seeking out “misleadingly comforting versions of history is a pattern we’ve seen again and again this year,” said Oliver.

Should Americans topple statues of George Washington? You bet, implied Oliver.

Since I share Oliver’s liberal political bent, I usually find his humor and political satire hilarious. But not this time.

I was sad to see that Oliver has apparently jumped on the Twitter bandwagon to judge and condemn figures from the American past using current standards of “woke” social justice activism but employing very little actual history.

To paraphrase Albert Einstein, everything should be made as simple as possible, but no simpler. In trying to pander to a youth audience, Oliver has made a complex story too simple.

I predict that Oliver will soon learn, as his countrymen King George III and Lord Cornwallis did back in the Revolution, that if you want to take down George Washington, you’d better deploy heavy artillery. And even then you may fail, as those estimable Englishmen did at Yorktown. John Oliver is no Cornwallis, and his ill-informed finger wagging was like a puny musket that appears to have gone off in his own face.

It would be a cheap shot to refer Englishman Oliver to the story that Abraham Lincoln used to tell about Ethan Allen visiting England just after the American Revolution. Allen wound up dining at the home of a British aristocrat who thought it would be clever to hang a portrait of George Washington in his outhouse. I’m sure John Oliver would enjoy Ethan Allen’s reaction to his host after returning from the loo. For a laugh, watch Daniel Day-Lewis deliver the punchline in this short clip from Steven Spielberg’s wonderful biopic Lincoln.

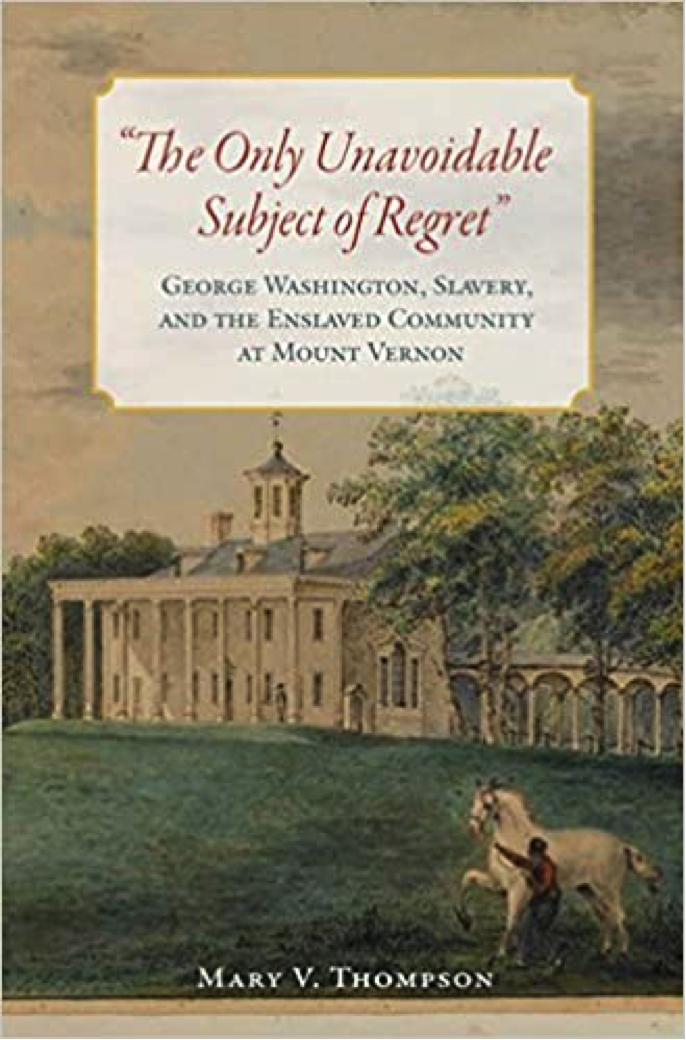

Fortunately, to get to the truth about Washington and slavery without trendy simplifications, there’s no need for cheap shots. Mary Thompson, librarian at Mount Vernon, has condensed 30 years of research on George Washington’s relationship to slavery in her detailed but readable book “The Only Unavoidable Subject of Regret”: George Washington, Slavery, and the Enslaved Community at Mount Vernon.

Thompson’s book is a primer on the economic and social life of the white and black community at Washington’s plantation home in the second half of the 18th century, covering such subjects as crops grown, farming innovations, white indentured servants, overseers (both white and black) and changes in the economy.

Thompson offers this context to tell a story of George Washington more nuanced than a social media meme or a punchline from a comedian.

Balancing Rigor and Care

Even if you’re talking about George Washington, there was no such a thing as a “good” slaveowner. Slavery was inherently about making people work for free, torturing them when they didn’t obey and separating families.

Thompson is clear that she admires Washington, referring to him as “one of the greatest men” who ever lived. But she does not candy coat Washington’s participation in slavery, which Thompson considers to be America’s original sin:

“Was George Washington a good slave owner?” or “He was good to his slaves, wasn’t he?” To anyone looking at this book to provide those answers, let me just say upfront that some of the worst things one thinks about in terms of slavery — whipping, keeping someone in shackles, tracking a person down with dogs, or selling people away from their family — all of those things happened either at Mount Vernon or on other plantations under Washington’s management.

According to European visitors, former slaves and members of the Washington family alike, George Washington balanced expectations for long days of hard work with a concern for the happiness and good health of his enslaved workers.

Expecting others to embrace his own work ethic and punishing daily schedule, Washington was not an easy man to work for, whether you were black or white; a soldier, a free tradesman or an enslaved worker. But George Washington also cared for his people, especially at Mount Vernon, where one foreign visitor wrote that Washington dealt with his slaves “far more humanely that do his fellow citizens of Virginia.”

Thompson’s conclusion is clear: Washington was not a horrible slaveowner but a better-than-average one. And there’s plenty of evidence that the Father of Our Country may also have been one of the fathers of the budding abolition movement, in a quiet but especially effective way.

Thompson provides context that shows just how complex was the story of Washington and his enslaved workers. To judge the man, you must understand at least some of this context.

Her most interesting point is that, against all odds, over the course of his lifetime, Washington learned to hate slavery and decided to work for its end.

Slavery was thousands of years old by the time Europeans brought it to the New World, and Americans inherited the peculiar institution from the British.

It may be hard to understand today, where freedom is the norm and slavery is illegal in every nation on earth, but before the American Revolution, here and everywhere, freedom was the exception and unfreedom was the rule. As many as 75% of people who immigrated to the 13 British colonies that became the United States may have been unfree laborers, either slaves or indentured servants.

As a member of the Virginia gentry, Washington was born into a world where most work was done by bound workers and where most people thought that unfree labor, organized in a hierarchy with white householders at the top, wives and children in the middle and indentured and enslaved people at the bottom, was an eternal part of society.

Yet, letters and other documentary evidence that Thompson presents show that as George Washington matured, he learned to hate the institution of slavery and developed a strong desire to see it end on a national level.

To a visiting British actor, the retired president explained,

Not only do I pray for it, on the score of human dignity, but I can clearly foresee that nothing bu the rooting out of slavery can perpetuate the existence of our union, by consolidating it in a common bond of principle.

Seeing how impractical abolition was during his lifetime, Washington at least wanted to free as many enslaved people under his control as he could.

This history is little known. And as more and more places take down statues of Confederate generals and other figures from history, Washington has become a target of renewed criticism for his role as a slaveowner.

Answering the Charges

As to the common criticisms leveled at George Washington today for alleged abuses of enslaved people, Thompson mostly exonerates Washington:

1. His Dentures Used the Teeth of Slaves

Yes, Washington did use teeth from enslaved people in his dentures. He bought teeth only from people who were willing to sell, a gruesome but common practice for poor people of all races in the 18th century. In the days before payday lending, people without property had few options to raise cash quickly. Poor people continued to sell their own teeth at least into the 19th century, as readers of Les Miserables can attest.

2. He Didn’t Free Slaves in His Will

This is wrong — Washington freed all the slaves he could in his will. Only in a narrow technical sense can anyone argue with this: Only one enslaved person, William Lee, who served as attendant to Washington during the Revolution, was freed on Washington’s death in December of 1799. But 123 others at Mount Vernon were granted freedom in Washington’s will to be emancipated on Martha’s death. However, following advice from friends, Martha decided to free all these people while she was still alive, about a year after Washington’s death. Another 40 slaves at a plantation in Tidewater Virginia controlled by Washington were ordered to be freed on a gradual schedule.

To claim that Washington didn’t free slaves in his will based on the timing when the manumissions went into effect is fundamentally dishonest. The truth is, he freed more than 160 slaves in his will, which was a huge accomplishment not only because of the financial value lost to his heirs but because it was so unusual among Virginia planters to emancipate so many people at once. As Thompson explains, at the time, this rare act attracted criticism from influential white people, who thought that Washington had acted rashly. By contrast, prominent black leaders were overjoyed.

3. Fine. Even if He Did Free Slaves in His Will, Why Did He Wait Until He Was Dead to Do It?

According to Thompson, it wasn’t greed or hypocrisy but lack of funds that prevented Washington from acting on his documented desire to free slaves during his lifetime. After the Revolution, during which he worked for eight years without a salary, Washington came back to a nearly bankrupt farm operation at Mount Vernon with failing crops and mounting debts. As he worked to fix his finances, Washington also brainstormed various schemes to transition his enslaved workers from slavery to freedom. In the end, his will proved to be the best instrument to accomplish the emancipation project he’d planned for more than a decade.

4. He Fathered A Black Child

There’s no evidence that George Washington fathered West Ford, who claimed to be his son by an enslaved woman named Venus, or any children at all by women in the enslaved community of Mount Vernon. Mixed-race children there were fathered by white overseers, tradesmen and workers on the estate or else by white men living in the neighborhood.

5. He Relentlessly Hunted Down Escaped Slave Oney Judge

Washington did in fact hunt down escaped lady’s maid Oney (or Ona) Judge, going so far as to enlist government officials to locate her in New Hampshire, where she had fled, and urge her to return. Washington did not pursue Judge out of spite or greed. Other slaves who had escaped from Mount Vernon were sought with far less vigor than Judge.

Her case was special because Judge was Martha’s special favorite and also because Judge was part of Martha’s “dower” slaves that she and George held in trust for the heirs of Martha’s first husband Daniel Parke Custis. George and Martha stood to suffer a large civil penalty if they lost any of the dower slaves. Washington’s death in 1799 did not lift fears that Custis heirs might try to recapture her, but Judge remained free, enjoying a long life in New Hampshire until her death at age 75 in 1848.

6. He Was a Racist

Compared to other founding fathers and certainly compared to other Virginia landowners, Washington can hardly be called a racist. His views on slavery changed as he matured, and his respect for black people grew as he had contact with them in different situations, especially as soldiers in the Revolution, where he not only agreed to accept black enlistment but then went on to desegregate the Continental Army. His famous meeting at his headquarters in Cambridge with the enslaved poet Phillis Wheatley in 1776, whose work he praised and who he addressed in a letter as “Mrs. Phillis,” shows that Washington was ready to recognize the humanity and even accomplishment of enslaved people.

7. Compared to Hamilton and Adams, Washington was Compromised by Slavery

Thompson doesn’t deal much with this issue, but it’s become common for people today to compare Washington with northern founders who didn’t own slaves, so I wanted to share here what I’ve learned from other sources.

No founding father had entirely clean hands when it came to slavery. Even Alexander Hamilton, famous for denouncing the peculiar institution, made compromises with the slave economy in his work as an attorney in New York City. While serving his term as president, John Adams, who never owned any enslaved people and also often criticized slavery, may have rented slaves from local owners in the District of Columbia to work at the White House.

As to Ben Franklin, in 1775 he helped start the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, but years earlier, as a young printer in Philadelphia, Franklin owned two slaves, George and King, who worked as personal servants. His newspaper, the Pennsylvania Gazette, commonly ran ads to buy and sell slaves.

And of course, these three, along with all other signers of the Declaration of Independence and Constitution from the North, acceded to the compromise with South Carolina and Georgia necessary to keep the nation together. It was a reluctant compromise though, not just for northerners, but also for George Washington, who applied the natural right of freedom to both whites and blacks and wanted slavery put on the road to quick extinction.

What if Washington Was Really an Abolitionist?

Was Washington a quiet activist to end slavery, not only at Mount Vernon, but throughout the United States? Thompson’s book might make you think so.

After 1775, Washington stopped buying new slaves, according to financial records for decades of operations at Mount Vernon. Letters confirm that he did this because he did not want to commit himself further to an institution he wanted to get out of. Later, when he had money problems and began looking for assets that he could sell for ready cash to pay debts, Washington resisted selling off enslaved people as he thought it cruel to separate families.

After the war and during his presidency, Washington knew that with the high visibility of his public persona, he could not come out publicly for abolition. That would scare away South Carolina and Georgia, whose representatives had made it clear that they would only join and stay in the federal union if they were allowed to buy and own slaves without interference from other states.

As Thompson explains,

If he had any doubts before about where the country stood on the issue of slavery, Washington could have had none after the Constitutional Convention: if the issue of abolishing slavery was pushed, the country would dissolve. While he could never bring himself to publicly lead the effort to abolish slavery, probably for fear of tearing apart the country he had worked so hard to build, Washington could, and did, try to lead by setting an example and freeing the people over whom he had control.

Yet, letters show that Washington quietly lobbied for an end to slavery--gradual and legislated by government rather than immediate and done by individual slaveowners--because it would be more acceptable politically. Washington feared that slavery would destroy the American union, and wanted the troublesome institution gone.

Though he was born and raised in the Virginia gentry, Washington identified more with states that were ending slavery, as six northern states did after the Revolution, than with those states that sought to continue it. According to Thomas Jefferson, Washington told Attorney General Edmund Randolph that if disagreements about slavery ever brought America to a civil war in the future, Washington said he’d side with the North over the South.

Washington even entertained several projects to gradually manumit his slaves during his lifetime, including an idea to start a plantation for freemen in the South American colony of Cayenne (today’s French Guiana) with the Marquis de Lafayette.

Explaining the quote in the title of Thompson’s book, Washington wrote near the end of his life about his own connection to slavery,

The unfortunate condition of the persons, whose labor in part I employed, has been the only unavoidable subject of regret. To make the Adults among them as easy & as comfortable in their circumstances as their actual state of ignorance & improvidence would admit; & to lay a foundation to prepare the rising generation for a destiny different from that in which they were born: afforded some satisfaction to my mind, & could not I hoped be displeasing to the justice of the Creator.

White Critics and Black Fans

While a few of his fellow white people approved of Washington’s unusual decision to free all the slaves he could in his will, other prominent white leaders criticized Washington for acting rashly.

Pennsylvania jurist Horace Binney wrote that “no good had come from [manumission] to the slaves, and that the State of Virginia was compelled to place restraints upon emancipation within her limits, for the general good of all.” Years later, in a history of the Washington family, a distant relative described Washington’s decision to free his slaves as “the…worst act of his public life.”

Some white writers claimed that Washington’s enslaved workers were better off in slavery and that they floundered in freedom. But Thompson explains that the people who settled near Mount Vernon in Fairfax County created a settlement called Free Town that became a model for black success in the 19th century.

That was partially due to the experience of working for George Washington. As Thompson writes, “Through a largely undocumented and largely unrecognized high pressure stint of learning by doing, Mount Vernon’s enslaved laborers became some of the most skilled mixed-crop farmers, fishermen, and stock breeders in the region.”

Many of the enslaved people freed by Washington had fond memories of Mount Vernon, and some freemen actually returned for years to volunteer their time to care for Washington’s tomb.

In a famous eulogy on Washington’s death in 1799, Rev. Richard Allen, a formerly enslaved Methodist minister in Philadelphia, recognized Washington as a leading ally for black freedom, “Our father and friend.”

Allen was one of the most famous black leaders in America at the time. Seventeen years later, in 1816, Allen would go on to found the first national black church in the United States, the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church.

As Allen put it in his eulogy in 1799, because Washington opposed public opinion and instead followed this conscience by freeing his slaves in his will, he

…dared to do his duty, and wipe off the only stain with which man could ever reproach him…he let the oppressed go free…and undid every burden…the name of Washington will live when the sculptured marble and the statue of bronze shall be crumbled into dust — for it is the decree of the eternal God that ‘the righteous shall be had in everlasting remembrance.’

Revisionist History, Revised

Thompson shares Richard Allen’s admiration for Washington’s actions against slavery and ultimately to free his own enslaved people. Yet, her sober prose style and abundant historical evidence makes a credible case that, along with everything else we’ve been taught about George Washington, the first president may turn out to be an unsung hero of abolition and even civil rights.

John Oliver says that Americans need a more accurate understanding of our history. If he really means that, then Oliver should get one of his staffers to read Thompson’s book and write him up a summary. Then, Oliver should go back on TV and apologize to Joy Behar and the rest of us for lecturing us to go back to history class when it turns out that Oliver was really the slacker who hadn’t done his homework.

The rest of us don’t need to wait for John Oliver to rework his sloppy oral presentation and try for a better grade. As students of American history, we should all do our own homework and listen to historians rather than social media. Then we’ll see that there’s no comparison between statues of historical figures that really should come down, like Confederate generals, and statues of George Washington and other founding fathers that should stay up.

Southern rebels like Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson and Jefferson Davis started a war to destroy the United States and to guarantee white supremacy for all time. Washington did the exact opposite. He fought to start and preserve the United States, the world’s first country dedicated to the idea that “all men are created equal.” Then, as his political ideas matured, Washington started working to apply revolutionary ideals of human freedom and dignity to Americans regardless of race.

As we reassess all dead white guys on horses from the American past, we may just find that George Washington’s reputation will rise, giving his story a new relevance for the problems of the 21st century. The founding father who seemed stiff and cold for so many years may turn out to have had a surprisingly warm heart and a soul with a thirst for justice.