Is This the Most Important Election?

The conventions are now behind us, and the post Labor Day period is often considered the launch of the full presidential campaign season. As in most election seasons, this one is being cast in apocalyptic terms by the two parties. “Do not let them take away your democracy,” former President Obama urged during his convention speech. “This is the most important election in our history,” President Trump countered.

Is Trump right? Is this the most important election in our history? Is democracy on the ballot, as Obama claimed? Or is that just a conceit, something we say every four years? Perhaps a look at some other crucial elections in our history will help to enlighten us.

The election of 1800 established the first peaceful transfer of power in the United States, one that almost didn’t happen. Without this, it is hard to see how America would have become a democracy. The election featured two men who were old friends and now political rivals: John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. They had faced each other in 1796, with Adams prevailing. Jefferson, who came in second, become vice president based on the original wording of the Constitution, under which electors voted for two people. The one with the most votes became president, while the runner up became vice president.

The two had a brief flirtation with bipartisanship at the beginning of Adams’ term, but things soon fell apart over lingering differences in the direction the new nation should take including over foreign policy. Relations with revolutionary France had fallen apart over the Jay Treaty, which was seen as pro-British. Adams ended up in a quasi war with France and his Federalist Party passed a series of bills known as the Alien and Sedition Acts. The Sedition Act was clearly pointed at Jefferson and the Republicans, making it illegal to publish “false, scandalous, and malicious writings against the United States.” Partisanship had spun out of control by the late 1790s, and actual violence between the two sides, both in Congress and in the streets, broke out.

This was the setting as the election of 1800 unfolded. Surprisingly, Jefferson and his vice-presidential candidate, Aaron Burr, tied with 73 electoral votes, while Adams received 65 electoral votes. The election was thrown to the House, but the Federalists began to consider extraconstitutional means to deprive Jefferson of the presidency. Jefferson then warned Adams that this “would probably produce resistance by force and incalculable consequences.” Ultimately Jefferson emerged as the winner after thirty-six ballots. While Adams peacefully gave up power, he refused to attend Jefferson’s inauguration. As David McCullough has written, the “peaceful transfer of power seemed little short of a miracle…and it is regrettable that Adams was not present.”

The election of 1860 took place when the future of the nation was literally at stake. Abraham Lincoln, a man who had risen from humble circumstances, had become one of the leaders of the new Republican Party in the 1850s. Lincoln wanted to stop the spread of slavery into the new territories that had been obtained during the Mexican-American War. His main rival for power, Stephen Douglas, believed that each territory should vote on whether to allow slavery, that popular sovereignty was the answer. Lincoln’s response is instructive. “The doctrine of self government is right---absolutely and eternally right—but it has no just application” to the issue of slavery, which Lincoln believed was morally wrong.

Lincoln, the dark horse candidate for the Republicans, emerged on the third ballot at the convention in Chicago. Douglas won the Democratic Party nomination, but it was a pyrrhic victory. The Democrats from the South had walked out of the convention and nominated Vice-President John C. Breckenridge as their candidate. To make matters worse, a fourth candidate joined the fray as John Bell of Tennessee ran for the Constitutional Union Party. Ultimately Lincoln prevailed in the election, winning solidly in the North and west, but barely gaining any votes in the South. By mid December, South Carolina seceded from the Union and the Civil War began in April when southerners fired on Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor.

The question at the start of the war was would the Union survive, but ultimately the next four years of Civil War would lead to the elimination of slavery in the United States and “a new birth of freedom” for the nation, as Lincoln framed it at Gettysburg. The question of who can be an American, of who is part of the fabric of our nation, continued to evolve. During a brief period known as Reconstruction, America began to live up to its founding creed, that all are equal. Amendments were added to the Constitution which formally ended slavery, provided for birthright citizenship and equal protection under the law, and allowed black men to vote. But the era was just a blip in our history, and the era of segregation and Jim Crow laws soon emerged and would not be removed until the Civil Rights protests of the 1960s.

The 1932 election occurred against the backdrop of the Great Depression. Herbert Hoover had been elected in 1928 as the “Great Engineer.” He had made a fortune as a geologist in mining and then had become involved in public affairs. “The modern technical mind was at the head of government,” one admirer wrote of the president. Hoover has often been cast as being a disciple of laissez faire when it came to the economy, but he in fact believed in “government stimulated voluntary cooperation” as historian David Kennedy has written. He took many actions early in the crisis, like getting businesses to agree to maintain wages and urging states and local government to expand their spending on public works. But Hoover was limited by his own view of voluntary action and could never bring himself to use the federal government to take direct action to fight the depression.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt had no such qualms. A rising politician in the early part of the 20th century, FDR had been struck down by polio in 1921. It made him a more focused and compassionate man who identified with the poor and underprivileged, as Doris Kearns Goodwin argues. Roosevelt began with some bold pronouncements, talking about “the forgotten man at the bottom of the economic pyramid” and of the need for a “new deal for the American people.” Those two words, which James McGregor Burns has written “meant little to Roosevelt and the other speech writers at the time,” soon came to define Roosevelt’s approach to the depression. FDR swept to victory, winning almost 60 percent of the popular vote and 42 of the then 48 states. The election established that the government had a responsibility for the well being of the people of the nation. FDR would eventually adopt the Four Freedoms as part of his approach, which included the traditional support for freedom of speech and worship, but also freedom from want and fear.

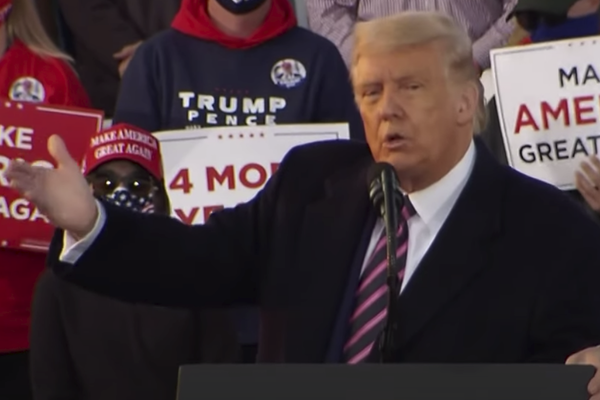

The 2020 election features each of the elements that made these prior elections so important. Democracy and the peaceful transfer of power are clearly on the line. Donald Trump has already called into question the fairness of the election, especially over mail in voting, and has begun once again to claim that he will lose the election only if it is rigged. One can imagine Trump refusing to leave office if he loses a close election to Joe Biden.

The unity of our nation is also as stake. Trump “is polarization personified” who has “repeatedly stoked racial antagonism and nativism,” political scientist Suzanne Mettler and Robert C. Lieberman write. Trump has even been encouraging violence on the part of his supporters over Black Lives Matter protests. “The big backlash going on in Portland cannot be unexpected,” Trump tweeted regarding the violence perpetrated by his supporters.

Prior to COVID-19, Trump’s economic and tax policies favored the already wealthy and contributed to an ever-worsening growth in income inequality. To their credit, the president and his party supported an aggressive initial stimulus package to assist businesses and individuals. The extent to which the Republican Party will continue to support aggressive government action in response to the economic damage caused by the coronavirus, in order to aid the middle and working classes rather than the wealthy, is an open question.

President Donald Trump may indeed be right, this is the most important election in our history. Just not for the reasons he believes.