Corporate Money Turns Democracy Upside Down in California Initiative Process

The California ballot initiative process, created in 1911 by the progressive movement to control the influence of corporations, has instead been turned upside down by massive corporate spending. Corporate interests now use referenda to defeat popular legislation and grassroots reform efforts.

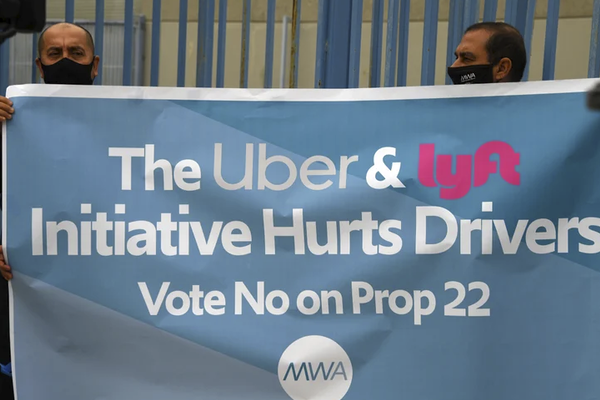

The most glaring example is the current fight over Proposition 22 on the November ballot, which has attracted a whopping $190 million in spending from Uber, Lyft and DoorDash. The measure, backed by the companies, would overturn a current California law defining their drivers as employees who must be paid a minimum wage and be eligible for unemployment insurance.

According to Ballotpedia, an independent tracker, this has become the most expensive ballot proposition in California history. Unfortunately, this massive outlay is only the latest in a long line of corporate efforts to sway public opinion on initiatives that impact their bottom line.

For example, in 2018, the dialysis clinic industry spent $110 million to defeat a measure to regulate their operations. In 2016, the pharmaceutical industry doled out $109 million to defeat drug price controls and in 2006 the oil industry spent $91 million in a successful effort to kill an oil extraction tax.

Hiram Johnson

If Hiram Johnson, the progressive governor who championed the ballot initiative process, were alive today he would be appalled. Johnson was first elected in 1910 on a platform of controlling “the interests,” specifically the Southern Pacific Railroad, which basically owned the legislature. Johnson was a liberal Republican, and a follower of “Fighting Bob” LaFollette, the progressive Republican governor of Wisconsin, who instituted an income tax, a railroad commission and a pure food law.

Although California’s proposition battles have attracted the most headlines, the Golden State was not the first to put initiatives on the ballot. South Dakota was the first to adopt statewide referenda in 1889, followed by Utah in 1900 and Oregon in 1902. By 1918, an additional 16 states implemented the practice.

As the progressive movement ebbed in the Roaring Twenties, interest in initiative process fell off. Between 1912 and 1969, less than three ballot initiatives per year, on average, appeared on the statewide ballot.

However, the power of the proposition for implementing major change jumped into national view in 1978 with the passage of California’s Proposition 13. This measure, sponsored by apartment owner Howard Jarvis, rolled back residential and commercial property taxes and limited the legislature’s ability to raise new taxes.

Awakened to the potential power of the initiative, grassroots activists and corporate interests alike rushed to qualify initiatives for the ballot. Between 1978 and 2003 there were 128 initiatives on the statewide ballot.

Easy to qualify

Getting on the ballot is not that difficult. Currently, 624,000 signatures are required for a basic or statutory referendum and 997,000 for a proposed amendment to the state constitution. The widespread use of paying signature gatherers makes the process easy for deep-pocketed interests. Attempts to ban the use of paid gatherers have been struck down by the courts.

With Californians facing a long list of ballot measures year after year, many are questioning the wisdom of the process. A 2013 survey of likely voters found that 67% said there were too many propositions on the ballot and 84% said that the wording on initiatives was “too complicated.”

This November, an even dozen measures will be up for a vote. They include rent control, dialysis clinic staffing (a second time), eliminating cash bail, voting rights for 17-year-olds and ending the state’s 22-year-long ban on affirmative action.

As for the $180 million spend on Proposition 22, Los Angeles Times business correspondent Michael Hiltzik recently observed “no other initiative campaign in California history — given that California campaigns are the most expensive in the country, that means U.S history — has come close to the gig companies’ spending on Proposition 22, even accounting for inflation.”

The spending has manifested itself in a barrage of TV ads and mailers. The campaign features Uber and Lyft drivers (presumably volunteers) asking voters to “save my job.” The TV ads feature drivers (often young mothers and fathers) who state that the only way they can make ends meet is by driving for Uber or Lyft.

Despite the ad onslaught, the ridesharing companies have an uphill climb to win approval. A poll released September 22 by the U.C. Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies found that only 39% of likely voters would vote “yes” and support the ride-hailing companies, compared with 36% who would vote “no” to retain current law with 25% undecided. Given that that in most cases undecided voters ultimately vote “no” on ballot measures, Proposition 22 could be wind up a costly defeat.

A number of studies in recent years have found that the cumulative effect of California’s multitude of ballot initiatives has been to reduce the power of the state legislature and make it difficult for cities, counties and school districts to raise funds. This, of course, is hardly what Hiram Johnson intended.

Can anything be done to restore fairness to the initiative process?

Some legislators have proposed raising the signature requirement or increasing the filing fee (now just $2,000). But as long as the federal courts equate corporate spending with free speech, those measures would do little to discourage wealthy special interests from using this policy-making tool.