Will Eugene Goodman Share the Fate of Frank Wills?

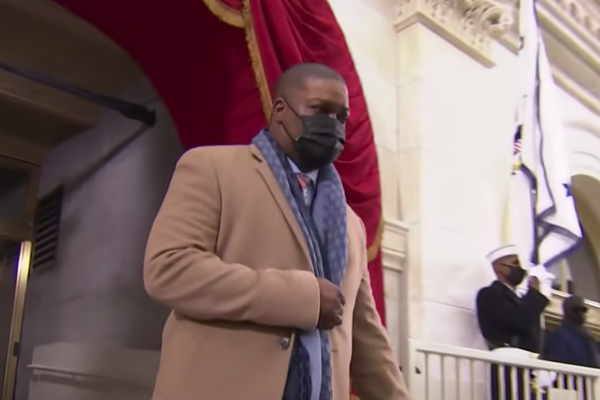

Capitol Police officer Eugene Goodman is honored at the inauguration of Joseph Biden, January 20.

January 6, 2021, will regrettably resonate in American history—a day comparable to June 17, 1972, when our nation’s democracy was also upended by its own president. Today it’s Trump. Half a century ago the culprit was Nixon, who had authorized members of his administration to infiltrate and burglarize the offices and homes of his political opponents. In an ironic twist of fate, two men, Eugene Goodman and Frank Wills, both African American, unexpectedly put their lives in danger to save their country from its leader.

On June 17, 1972, Wills, a security guard, patrolled the Watergate Office Building in Washington, D.C. when he shrewdly detected burglars inside the facility and reported it to the Metropolitan Police Department. His actions that morning led to a national scandal and ultimately ended in the resignation of President Richard Nixon. Despite his brush with fame, Wills was never able to enjoy its benefits and died at the age of 52, alone and in poverty. Not surprisingly, there is already a sense of resignation that Goodman will be forgotten too. Will United States Capitol Police (USCP) officer Goodman, who cleverly lured rioters away from the Senate chamber during the mob attack on the Capitol, suffer the same fate as Frank Wills?

It’s a fair question given how the United States has historically mistreated African Americans, but the short answer is probably not.

Knowing few details about Officer Goodman at this point (he’s a ten-year veteran of the USCP department and an Iraq war veteran), but in view of his current position as a full-time, federal government employee with a pension and job security—something Wills always had wanted, but was unable to obtain—in and of itself distinguishes these two men. Frank Wills was an hourly worker, making slightly above minimum wage. He had no job protection, no pension. He had minimal security training and was a high school dropout. Once the spotlight shined on Wills, he had little to offer the world.

It is also a different era. Although we’ve recently been reminded how little has changed in our nation’s progress when it comes to racial equality, there are many more opportunities for people of color today than there were fifty years ago.

Should Goodman hire an agent like his counterpart and try to reap his fifteen minutes of fame?

It didn't work for Wills.

When Nixon finally resigned, twenty-six months after the botched burglary at the Watergate, Wills’ fame peaked and he took full advantage of it. From selling photographs of himself for a buck a piece to charging reporters for interviews, it was so blatant what he was trying to do that the New York Times and other newspapers called him out for it. Perhaps, his shortcomings also had to do with whom Wills hired (the agent/attorney would later be disbarred for “unprofessional conduct”) than whether or not there truly were opportunities to monetize his newfound celebrated status.

Again, different times, more opportunities, and, to be fair, Goodman—and I say this with all due respect to Frank Wills, who is the subject of my forthcoming biography—was in a situation that was far more dangerous and his actions proved far braver than Wills’. As anyone can attest from the video footage, Officer Goodman’s professionalism and courage merited formal recognition. He’s recently been nominated by members of Congress for the Congressional Gold Medal, and was an honored guest of Congress at Wednesday's inauguration. The officer’s actions might be the only silver lining we can discern from this violent, unprecedented episode that is now a part of our nation’s history.

Frank Wills never got his dues, but I sure hope Eugene Goodman gets his.