"Hands Off Until He Was Safe Over": David Reynolds Urges Biden to Look to Lincoln

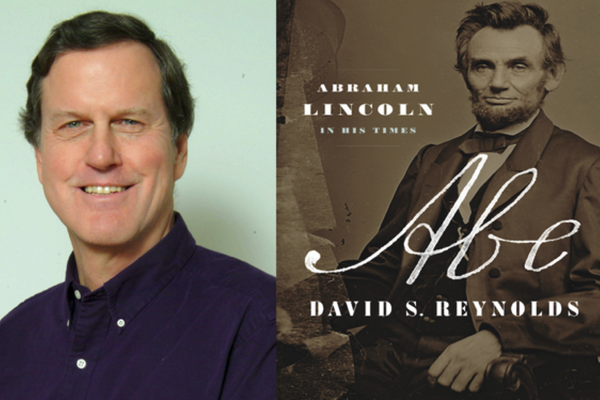

Historian David S. Reynolds recently published Abe: Abraham Lincoln and his Times, a cultural biography that shows how the 16th president was shaped by the many social currents swirling in the young United States.

Reynolds is a Distinguished Professor at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. He is the author of five other books including Walt Whitman’s America: A Cultural Biography (winner of the Bancroft Prize); Beneath the American Renaissance; John Brown, Abolitionist; and America in the Age of Jackson.

Reynolds spoke with the History News Network about Joe Biden’s election and how the President-elect might take lessons from Lincoln on unifying the country after a divisive election.

Q. The November election and its aftermath have left our country divided, but the hostility is not nearly as severe as in March 1861, when Lincoln took office. Describe the scene at that inauguration.

Abraham Lincoln delivered his first inaugural address during the worst crisis in American history. Between November 6, 1860, when Lincoln won the presidency in a four-man race, and March 4, 1861, when he gave the inaugural address, seven Southern states seceded from the Union institution and formed what they called a separate nation, the Confederate States of America, with its own constitution, president, and legislature. Soon thereafter, four more Southern states would secede, while four border states would hang in the balance.

By the time of his inauguration, Lincoln had received several threats of assassination. A report came that an attempt on his life would be made during the inaugural parade. At noon Lincoln rode in an open carriage with the outgoing president James Buchanan and two senators in a procession that led to the Capitol. The carriage was surrounded so densely by cavalry and marshals that it could not be seen by the spectators that lined Pennsylvania Avenue. From rooftops, sharpshooters watched the street, sidewalks, and windows. When Lincoln’s carriage reached the Capitol, the president entered the building through a boarded tunnel built for the occasion.

By the time Lincoln emerged on the portico of the Capitol, a bright sun was shining. Standing on the portico steps in front of tens of thousands of people, with the unfinished Capitol dome bristling with cranes behind him, Lincoln delivered a speech that was a bold rhetorical effort to repair the Union.

He used every strategy in his oratorical toolbox. He reasoned against secession, calling it unconstitutional and conducive to anarchy. America lived by majority rule, he declared, and the people had spoken definitively in the presidential election. His administration would respect the Constitution by leaving slavery untouched where it already existed and by returning fugitives from bondage, as long as they were granted due process. In his stirring peroration, he insisted that the North and South must be friends, not enemies.

Along with offering reason and conciliation, Lincoln stated his administration’s policy “to hold, occupy, and possess the property, and places belonging to the government, and to collect the duties and imposts.” Southerners took this to be a coercive threat of force by a “Black Republican” president.

Within eight weeks of giving the speech, Lincoln was presiding over a war that would last for four years and would cost some 750,000 American lives.

His masterly language could not stave off bloody civil war.

Q. President-elect Biden has promised to be a leader for “all Americans.” Are there any lessons of Lincoln’s presidency that President Biden might heed as he seeks to heal a divided nation?

To achieve his stated goal of being a leader for all Americans, Biden should continue to do what he did in the 2020 campaign and what Lincoln did before him: that is, position himself near the center and stay there.

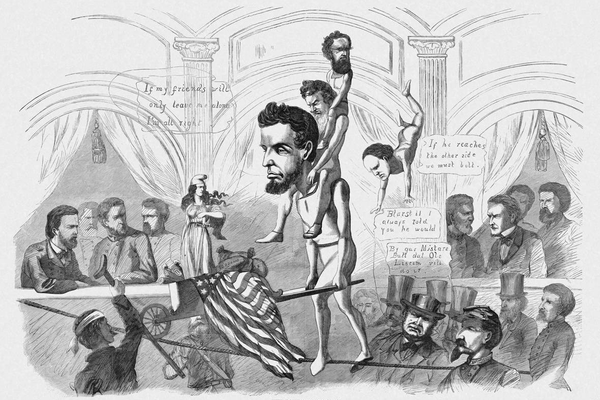

In the campaign, Biden channeled Lincoln, duplicating a strategy that led to comparisons between Lincoln and his era’s most famous tightrope walker, the French acrobat Charles Blondin, who dazzled Americans with his tightrope walks, the most famous of which were his repeated crossings of Niagara Falls. Advancing across the rope, Blondin performed amazing tricks: somersaults, flips, headstands, pushing a wheelbarrow and even walking across with a man on his shoulders.

For journalists and political cartoonists, Lincoln was Blondin — a politician who kept to the center, carefully avoiding extremes in his party. He won the Republican nomination in 1860 because he was known as a moderate who showed the capacity for stabilizing the nation at a time when it was deeply riven over slavery. The worst thing he could do, he knew, was to inflame extremists on either side of the issue.

Thomas Nast depicts Lincoln as tightrope walker Charles Blondin

Lincoln’s moderation, of course, was not enough to prevent Southern secession or the descent into Civil War. Yet, during the war, it was Lincoln himself who observed the similarities of his task with Blondin’s. Several times, leftists in his party— in a day when Republicans were the liberals and Democrats were the conservatives — attacked him for not making the Civil War an explicitly antislavery war instead of one fought to restore the Union. When antislavery radicals complained of his slowness on slavery, he asked them to suppose Blondin was crossing Niagara while pushing a wheelbarrow loaded with everything valuable in America. Would they shake the cable or distract him by shouting, “‘Blondin, a step to the right!’ ‘Blondin, a step to the left! Blondin, stoop a little more—go a little faster—lean a little more to the north—lean a little more to the south.’?” “No,” he added, “you would hold your breath as well as your tongue, and keep your hands off until he was safe over.”

Lincoln’s point was that he, too, was undertaking a delicate strategic balancing act. If he came out too strongly against slavery in the early going, he could lose the loyalty of the slaveholding border states, in which case, he thought, the North might as well surrender at once to the South. “I think to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to lose the whole game,” he wrote.

When the very future of the United States was at stake, then, Lincoln saved the nation by remaining centered while pushing incrementally to the left, toward social justice — like Blondin walking across his rope, adjusting his balance as the conditions demanded.

By staying balanced on the political tightrope, Biden won the support of both wings of the Republican Party and, more importantly, the majority of American electorate. His success shows the wisdom of recent plea by centrist Democrats for the party to abandon self-destructive references to socialism and defunding the police.

Biden’s vow to work as hard for those who didn’t vote for him as for those who did is, potentially, today’s version of Lincoln’s pledge to act “with malice toward none; with charity for all.” By centering himself between far-left radicalism and right-wing extremism and adjusting his balance as the moment demands — he can advance a forward-looking agenda without alienating average Americans or losing support within his own party.

Q. Lincoln’s second inaugural address in 1865 has been acclaimed as his finest speech. What qualities make it so memorable?

Minimizing the personal, Lincoln’s second inaugural address was directed at the entire nation. Focused, elegantly balanced, suggestive in every phrase, it offered healing to a nation ravaged by four years of bloody war. It did so by assigning meaning to the war without sounding partial or smug.

Lincoln avoided one-upmanship in his rhetoric. He did not speak for one side. He made no mention of South or North, Democrat or Republican. He talked about “all” and about the “parties” involved. Four years ago, “all thoughts” were turned toward war; “All dreaded it— all sought to avert it.” “Both parties deprecated war; but one of them would make war rather than let the nation survive; and the other would accept war rather than let it perish. And the war came” [underlining added].

The collective pronouns helped to detach the war from a particular section or party. All Americans, he was saying, dreaded war; but “the war came,” like an inexorable force. Even in describing the war itself, Lincoln used the rhetoric of unity: both sides expected a short war, both sides prayed to the same God, and the prayers of neither were fully answered.

He directed this language of unity toward a clever debunking of those who evaded the fact that slavery was the actual cause of the war. Many Southerners liked to attribute the war to other factors— the incompatibility of Southern Cavaliers and Northern Puritans, the sovereignty of the states, and so on. A Louisville newspaper typically insisted that “the slavery question is merely a pretext not the cause of this war,” which in fact resulted from “the hereditary hostility, the sacred animosity and eternal antagonism between the two races engaged.” Lincoln, by saying that “all knew” the war was about slavery, was discarding such evasions and returning to the real cause of the war.

“With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right”— the flowing phrases, made resonant by Lincoln’s use of parallelism, are so fixed in the national memory that it is difficult to hear how they must have sounded in March 1865. If “malice toward none” and “charity for all” may have meant that Lincoln was willing to be fair to Southerners during Reconstruction, “firmness in the right” suggested that, whatever happened, he would not bend in his devotion to civil rights.

In the last sentence of the speech, Lincoln invited Americans “to bind up the nation’s wounds,” to care for soldiers, widows, and orphans, and “to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves, and with all nations.” Here, all- embracing compassion merged with a demand for human rights; the peace Lincoln envisaged was not only “lasting” but also “just.”