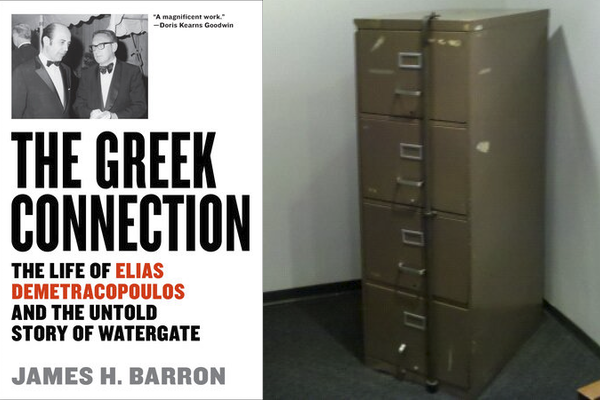

Gordon Liddy and the Greek Connection to Watergate

Did this Democratic National Committee filing cabinet contain damaging evidence of an illegal contribution to the 1968 Nixon campaign by the Greek military dictatorship, rooted out by journalist Elias Demetracopoulos?

Obituaries of G. Gordon Liddy, one year shy of the 50th anniversary of the bungled Watergate break-in that he masterminded, remind us how history morphs with new information and changing attitudes.

Just what was Liddy seeking in the offices of Democratic National Committee chairman Larry O’Brien? It remains a mystery. After he transformed himself from a tight-lipped, Hitler-admiring political operative to a self-promoting right-wing media entertainer, Liddy embraced some far-fetched conspiracy theories touted by Nixon admirer Roger Stone and others. These fanciful tales were designed to implicate others in the Watergate crimes and exonerate Nixon and himself.

But in his more contemporaneous 1980 autobiography, Liddy said the purpose of the June 17 break-in, as ordered by Nixon aide Jeb Start Magruder, was to “find out what O'Brien had of a derogatory nature about us, not for us to get something on him or the Democrats.”

According to then-White House counsel John Dean, it was a fishing expedition. Magruder told Liddy to “photograph whatever you can find,” and Howard Hunt, Liddy’s political sabotage co-conspirator, told the burglars to “look for financial documents—anything with numbers on them,” especially if it involved “foreign contributions.”

That search would likely have included evidence O’Brien possessed concerning a large illegal transfer of cash, nearly four million in today’s dollars, from the Greek dictatorship to the 1968 Nixon campaign. The bagman for that payoff was Greek-American tycoon and uber-GOP fundraiser Tom Pappas, later named on the Watergate tapes as “the Greek bearing gifts.”

Pappas had convinced the Greek military junta, which had recently overthrown its democratic government, that underwriting the Nixon-Agnew campaign would be a good investment. The whistleblower in 1968 was Elias Demetracopoulos, a controversial and scoop-hungry Greek journalist whose exposes had so angered American officials that the CIA and State Department had long tried disinformation campaigns to destroy his reputation. After the junta took over in 1967, Demetracopoulos escaped to the United States. Changing from journalist to activist, he wanted to generate American opposition to the junta, restoring Greek democracy from Washington. After Nixon’s running mate Spiro Agnew endorsed the junta in September 1968, breaking a promise of neutrality, Demetracopoulos investigated, uncovered the secret Greek money trail, and met with O’Brien twice in October at the Watergate trying unsuccessfully to get him to expose the plot.

At the time, support was soft for all three candidates: Nixon, Hubert Humphrey and George Wallace. This lack of enthusiasm meant a higher-than-usual possibility of last-minute switches spurred by a late campaign disclosure. The Greek money revelation would have exploded the so-called “new Nixon” image campaign. That alone could have changed the outcome of the second-closest presidential contest in the 20th century. The victory margin was less than one percent. A shift of fewer than 42,000 votes in only three states would have thrown the outcome into the Democrat-controlled House of Representatives.

The Nixon people knew fragments about Demetracopoulos’s 1968 disclosure to O’Brien. For years it caused them great anxiety. In 1969, Jack Caulfield, handling wiretaps and political surveillance for Nixon, sent John Ehrlichman a confidential memorandum titled, “Greek Inquiry.” In 1970 John Dean became aware of anti-Demetracopoulos smears. In July 1971, Elias testified before the House Foreign Affairs Committee, against the Greek dictatorship -- and against Pappas.

In that hearing, he hinted that he would disclose more about the 1968 money. So, Pappas and his allies tried different approaches to get both the Greek and American governments to attack Demetracopoulos. Nixon’s hatchet man Charles Colson took Elias to lunch in September 1971 to warn him not to criticize Pappas. Pappas menaced him directly. In early 1972, Attorney General John Mitchell publicly threatened Demetracopoulos. He tried to have him deported, which would surely have led to his torture and likely death.

The evidence Demetracopoulos gathered and presented in 1968 was still in O’Brien’s files in June 1972, and there is strong circumstantial evidence that it was part of what the burglars were looking for in the Watergate break-in. Liddy told me he was aware of Demetracopoulos and his co-conspirator Hunt knew him from his days with the CIA in Greece. Jeb Magruder admitted to historian Stanley Kutler that information on the Greek money would have been part of what the burglars were seeking. Years later Harry Dent, White House counsel and an architect of Nixon’s Southern Strategy, told Demetracopoulos that the Greek-money origins of Watergate “makes sense.” Congressional investigations to explore these connections were repeatedly blocked.

Before we are inundated with memorial reflections on the significance of the events of June 1972, we should consider that the roots of Watergate likely extend back to the 1968 Nixon campaign. Timely disclosure of the 1968 illegal money transfer could have meant a Hubert Humphrey victory, meaning no President Nixon, no Watergate break-in, and a different course of history.