The View from the New York City Hiroshima Peace Vigil

We hid under a table from a real though unseen threat There we stared into each other's eyes and waited as our fourth grade teacher taught us. Bobby Allan and I learned then to ridicule the “duck and cover” drills that the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962 inserted in school days. Too young to read John Hersey's Hiroshima, we were old enough to think for ourselves.

With Mom shopping and Dad at his office we were in charge. Aware with childhood clarity as sirens wailed that a nuclear bomb would vaporize us and table, apartment and building, we crawled out to resume “Challenge the Yankees,” a baseball board game that enthralled us for hours. We were nine years old.

McGeorge Bundy, Air Force General Curtis Lemay and other seasoned White House advisers, meanwhile, pressed President John F. Kennedy to authorize “a surgical strike” to destroy Soviet missiles installed in Cuba. Poised under pressure and having learned from the Bay of Pigs fiasco to mistrust the warlike palate of public men, the Chief Executive shrewdly declined.

His tactics of a naval quarantine to halt Soviet ships moving to and from the island, responding to Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev's conciliatory private letter while ignoring his hostile public remarks, and permitting him to save face with a US pledge to, six months later, remove obsolete Jupiter missiles from Turkey, preserved peace. A nuclear test ban treaty was their milestone later achievement.

With Kennedy dead the next year and Khruschev thereafter deposed, nuclear arsenals have massively grown; nine nations had 9,500 combine nuclear warheads in active service in August 2020, the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute reports. Russia and the United States held 90 percent of those weapons. India and Pakistan – often in conflict over Kashmir – had portions. So did China, the United Kingdom and France, plus Israel and North Korea.

The claim that “mutually assured destruction” preserves peace through nuclear deterrence, a frequent refrain since the Sixties, pales as misguided notions of national prestige place nuclear arms in politically unstable lands.

The “power of the people” manifested in one million of them marching on June 12, 1982, past the United Nations' New York headquarters during its Second General Assembly Session on Disarmament. The march made nuclear abolition seem likely. “I've been on marches against violence, against nuclear war, since I was fourteen,” folksong legend Joan Baez said from the Central Park rally stage, “and this is really the first time in my lifetime that I've seen the consciousness of the people of this country waking up.” Since then, it's slept.

Catholic activists have often enacted the Biblical injunction to “turn swords into plowshares,” in civil disobedience actions against nuclear weapons sites that are underreported but harshly punished. The Kings Bay 7 Plowshares, for example, presently serve prison terms for “trespassing and property damage” at a Georgia naval submarine base where they hammered on a Tomahawk missile, unfurled a banner (“The Ultimate Logic of Nuclear Weapons: Omnicide”), and read from Pope Francis’ statement against nuclear weapons.

Possession of nuclear weapons is immoral, the Pontiff declared because it destroys whole cities and wastes resources that could improve people’s lives and protect the environment.

“200 Plowshares Actions involving 101 men and women have happened since 1980,” the Catholic Worker’s Art Laffin has said. All, as the late Jesuit priest and poet Dan Berrigan wrote in Testimony, “labor to break the demonic clutch on our souls of the ethic of Mars, of wars and rumors of wars, inevitable wars, just wars, necessary wars, victorious wars, and say our 'NO' in acts of hope.”

Irony lies in US efforts against Iran's acquisition of nuclear arms, as our 1945 atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan begat the hydrogen bomb, the Cold War arms race and our collective current peril.

The Nuclear Threat Initiative, a nonpartisan nonprofit Washington organization that former Senator Sam Nunn and CNN founder Ted Turner launched in 2000, has produced documentary films warning of nuclear weapons and lobbied against using uranium and plutonium isotopes for fission reactions. NTI on the August 6th anniversary of Hiroshima's atomic destruction launched a symbolic “#Cranes for Our Future worldwide effort to spread a message of hope” by social media posts of folded origami designs. “Catastrophe outweighs our capacity,” NTI's website warns in seeking donations.

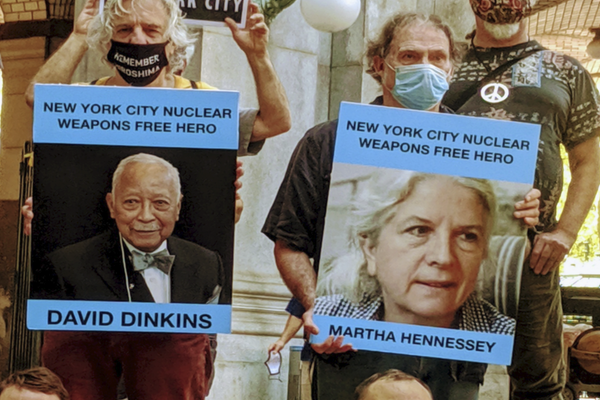

The New York Campaign Against Nuclear Weapons convened a Hiroshima Peace Vigil near Manhattan’s forty-floor Municipal Building. Holding aloft portraits of the Fellowship of Reconciliation's Bayard Rustin, the War Resisters League's David McReynolds, June 12th Lead Organizer Leslie Cagan, former New York City Mayor David N. Dinkins, and other “Nuclear Free Heroes.” Members heard remarks by Mitchie Takeuchi, Director of the “Vow From Hiroshima” documentary and the granddaughter of Hiroshima survivors, called Hibakusha. Seth Shelden, United Nations Liaison to the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons and Bud Courtney of the New York Catholic Worker also spoke.

Brendan Fay, Irish gay activist and NYCAN organizer, highlighted the legacy of LGBTQ New Yorkers in the global movement for nuclear disarmament: “Eyes opened, hearts broken at injustice and death, ours is a cry and call to rise for another world, another way of being human together,” Fay said. “The power and impact of civil society campaigns around the world – I believe that's where hope lies.” Participants shared images and messages with other groups around the world, he added.

“A good event,” I reflected, scribbling notes. Brooklyn bound on the A and F trains, I held my head high, heart full from the group's determined yet loving intent. Yet my mind placed the proceedings in context. Midday traffic drowned out mic-less speakers. The shady courtyard location hid us from passersby to persuade. The forty-five minute program, done before noon, lost touch with any government staffers not working from home.

A petition urged Council Speaker Corey Johnson to allow floor votes on Council Member Daniel Dromm's proposal to divest $475 million in public pension funds from Honeywell International, Lockheed Martin and other corporate “defense” contractors that derive wealth from nuclear weapons. The bill has languished in committee since a packed public hearing last year. The city's five accounts comprise half a billion dollars; the Dromm measure would enhance a 1983 law “to prohibit the production, transport, storage or deployment of nuclear weapons within New York City.”

A political culture beset by COVID-19, corruption and crime portrays the nuclear threat as a fringe issue, but we ignore it at our peril. Will the public awaken to redeem the faith of the prophets who pay dearly for peace? Can we both here and abroad – as Rodney King once implored in Los Angeles – learn to just get along, before the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists cries out that its Doomsday Clock strikes twelve?