9/11's Memorials and the Politics of Historical Memory

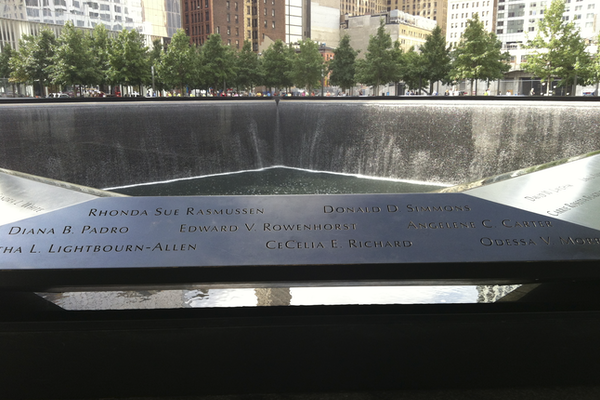

National 9/11 Memorial, Manhattan. Photo by author.

The post-9/11 era, which effectively began shortly after the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, has decidedly come to an end. Shaped not only by the loss of life on 9/11 but also by all that ensued in its wake, including the long wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, it was defined by fears of foreign terrorism, security culture, and a xenophobic and jingoistic form of patriotism. But the post-9/11 era was also significantly shaped by an under-appreciated force: the culture of memory.

As the 20th anniversary of 9/11 looms, it makes sense to reflect on this preoccupation, if not obsession, with memory. The urge to memorialize two decades ago was swift and strong, rising out of a deep sense of grief and loss. Over one thousand 9/11 memorials were built around the country and around the world. Many of these memorials were prompted by the decision of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey to hand out pieces of steel recovered from the site for memorials from 2010 until 2016. In New York, the 9/11 memorial and museum garnered extraordinary attention when they opened in 2010 and 2014. They also cost, together, almost $1 billion, a significant percentage coming from public funds.

Memorialization has been a nationally affirming enterprise, providing comforting narratives of national unity whose coherence nonetheless required the exclusion of many aspects of the event. With memorials being built well into the 2010s, it seemed increasingly that the surfeit of 9/11 memory was not about 9/11, or even those who died that day. Rather it reflected a desire to return to that post-9/11 moment of national unity, in which, however falsely, the nation seemed to speak with one voice: we are Americans.

What does it mean to remember 9/11 20 years later, when an entire generation has been born since? The memory-focused rebuilding of Ground Zero in lower Manhattan most painfully raises this question. Does anyone still care that One World Trade Center, formerly known as the Freedom Tower, is 1,776 feet tall in a gesture of patriotism? Or, that the $4 billion publicly-funded Oculus shopping mall (excuse me, transportation hub) has a skylight that opens on the anniversary of 9/11? The 9/11 museum, which tells a nationalistic story of 9/11 as an exceptional historical event and sells 9/11 hoodies and souvenirs in its gift shop, looks increasingly dated. Both the museum and the memorial are hugely expensive to run, the memorial because of its water features and security costs. The museum’s business model of selling entry tickets to tourists for $26 has been challenged by the pandemic, forcing it to furlough or lay off more than half its staff and cancel its plans for 20th anniversary special exhibitions. It has become the subject of debate about its relevance a mere seven years after its opening.

Despite the proliferation of 9/11 memory, a notable shift in national memorialization was signaled when in 2018 the National Memorial for Peace and Justice and Legacy Museum opened in Montgomery, Alabama. A memorial to over 4,000 victims of lynchings, it demands recognition that terrorism is not a new or foreign aspect of American history, but has long been a part of the US national story as racial terrorism. The Legacy Museum re-narrates the US myth of racial progress to argue that the contemporary mass incarceration of Black Americans is evidence that slavery never completely ended.

National Memorial for Peace and Justice and Legacy Museum, Montgomery, Ala. Photo by author.

Here, memory is being deployed not to uphold a myth of national unity, as 9/11 memory did, but to demand that the national script be revised. It is notable that Bryan Stevenson, who founded the memorial and museum through the Equal Justice Initiative, felt that memorialization was the best strategy to raise public awareness about the legacies of slavery. At the same time, long fought-over Confederate monuments have been toppled and removed, a reckoning with the past that once seemed impossible and now seems inevitable.

We don’t know what the new era we have entered will bring. But the demand that the nation confront its own history of terrorism has been activated. This means remembering terrorism not as a force that comes from outside but as a fundamental aspect of the American project of settler colonialism and slavery that lives on today. The memory of this past must be confronted in the present. To recognize the history of US terrorism is not to demand shame but to open up the opportunity for the nation to move forward from its difficult histories.