Flying the Confederate Battle Flag in the North is a Special Sort of Disgrace

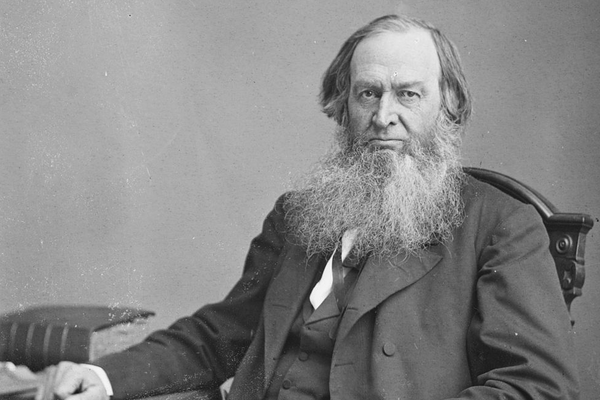

Abolitionist Gerrit Smith of upstate New York, photograph by Matthew Brady, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

New York is not a place where confederate battle flags should be flying. And yet there are more here now than ever before. I saw dozens of them while driving on country roads through upstate counties this year. They fly from private homes, mainly in rural areas, and I even saw one hanging from a run-down house in the middle of my hometown of Oneida, just around the corner from the Post Office.

Upstate New York State was once the most pro-Lincoln and anti-slavery part of the Union. Rebel flags fly on the same streets and rural roads from which men left their families to fight and die in the Civil War. The flag is not only an indecent symbol. In New York, it’s an assault on history and a sign of disrespect to our forefathers. Those who fly it are seeking attention. But ignoring it is also a dishonor.

Why might people think that flying the confederate battle flag is acceptable? Some may be fully aware of its racist associations and agree with that. I suspect more of those who began flying it recently see it as a symbol of rebellion against a tyrannical government, something like the ‘Don’t Tread on Me’ flags borrowed from the American Revolution (which are also more prominent now than ever). The use of the flag in the Dukes of Hazzard and by Lynyrd Skynyrd in the 70s and 80s might have made flying the flag seem mildly unruly but in a way that dissociated it from being a hate symbol. Then, it came across as an almost tongue-in-cheek symbol of hillbilly fun rather than anything inherently evil. But those days are gone and now no one can or should see it in that way.

The idea that flying the rebel flag was ever anything other than a symbol of anger and hate lost any credibility it ever had with the Charleston church massacre of 2015. Since then, the battle flag has been removed from the Mississippi state flag and there has been a reckoning in the South with the flag and its meanings. But it has morphed in the Trump years into one of the many symbols of anger and hostility against non-Trump supporters of all sorts, including black and white “F*** Biden” flags that are also not difficult to find flying, sometimes from the same flagpoles.

The city of Oneida is an interesting example of the how the present jars against the past. In the 1850s, the town’s main newspaper, The Oneida Sachem, was stridently anti-slavery. Nearby in the village of Peterboro was the home of Gerrit Smith, one of the most prominent abolitionist voices in the North. He was a founding member (and one-time presidential candidate) of the Liberty Party, the first and only one at that time that was committed to ending slavery. In the presidential elections of 1860 and 1864, Lincoln’s Republican Party received overwhelming support in central New York. It was the backbone of the party and of the war effort while most other parts of the North were more strongly split, with some backing Lincoln and others supporting the anti-war and sometimes pro-slavery Democrats.

When the Civil War broke out, the Presbyterian Church in Oneida, just around the corner from where I saw the confederate battle flag flying this year, made their own United States flag. It was impossible to buy one. They kept it flying from their steeple throughout the war until (as the church’s 1894 semicentennial history says) it was “whipped into shreds.” The church supported the war effort by sending food and supplies, and prayed for the young men from Oneida who served. “Two brave boys from the Sunday School,” it says, “did not return.” It would be an exaggeration to say that there was no dissent or disagreement with Lincoln or with the abolition of slavery in central New York, but there was certainly less there than in most other parts of the country.

The people flying these flags in New York are a small but noticeable minority who are forcing their views on many people who are disgusted by them. Whether we should ban the flying of the flag or not is an interesting question. If we do, some argue, it will further substantiate the claims of those why currently fly them – that they are living under an increasingly tyrannical, controlling government. It would be far better if they became more aware of why it is objectionable and chose to pack them away themselves. It is deeply disrespectful to people whose ancestors lived in the system of slavery and white supremacy for which that flag stands. But it is also a sign of disrespect for the people who sacrificed their lives in the Civil War.