Kyle Rittenhouse's Trial Will End in a Verdict. The Nation's Trial By Ordeal Won't

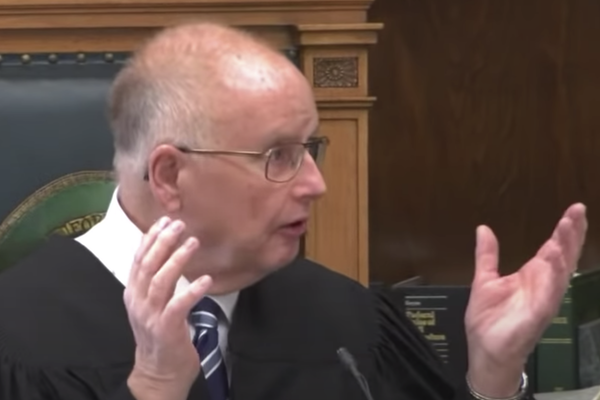

The judge is never meant to be the center of news stories in a trial—and certainly not in a trial that has become a microcosm for American politics. The trial of Kyle Rittenhouse is winding down. Closing arguments will begin on Monday. And all around the nation, people are watching to see what the verdict will be. And the judge in charge of the trial, Bruce Schroeder, has managed to become a central figure in the reporting.

When he led the jury selection on November 1, Schroeder opened his comments with a brief discourse on the history of the law. And while preparing to discuss the importance of the jury system in America, he decided to give the long history, starting back, “A thousand years ago, a case like this would have been tried. Well, let’s go back even further. Let’s go back to the—I’m sure you remember it. The fall of Rome in 476 and when Rome fell the world changed dramatically.” He says that the fall of Rome led to the end of the jury system, replaced by two things—trial by combat, subject of the recent movie The Last Duel (which he referenced)—and, more interestingly, trial by ordeal.

See transcript of Judge Schroeder's remarks below.

Trial by ordeal is exactly the kind of thing that makes calling something “medieval” a casual pejorative. Schroeder certainly presented it as such, saying, “the concept was that a person would be made to walk across for example a bed of coals, burning coals, or stick her hand or his hand into a boiling water, and depending on the healing period, if the person recovered sufficiently and this was blessed you know as so it would be a message from God, that was determined if he didn’t come out too badly he was innocent. If he did his punishments had just begun.” The idea, of course, is that people in the Middle Ages were superstitious, illogical, and ignorant. The trial by ordeal, the idea that walking across coals or putting a hand in boiling water was a message from God about innocence, seems absurd.

And it is. Because much like those notions of the Middle Ages, that idea of the trial by ordeal is fundamentally untrue. A trial by ordeal was about the court of public opinion, about the community and their decisions about innocence and guilt. And whatever happens next week, the Rittenhouse trial has indeed become a trial by ordeal—one where the public is making decisions, regardless of what is happening in the court room, and not in a way that is bringing consensus and closure. And it is one in a long train of American legal battles wherein competing interpretations of guilt reveal more about the society than the case itself.

The social nature of trial by ordeal can be illustrated with an example from that most violent of episodes, the First Crusade. A preacher who had been leading the march from Antioch to Jerusalem in 1098 was accused, essentially, of fabricating celestial visions. He was put on trial; witnesses came forth to support his cause, and he won. But in the aftermath, so much ill will was generated that he volunteered for a trial by ordeal. He would walk between two great piles of fire, promising to come out unhurt. And here is where it all gets tricky—we do not know what happened next. Much like in the aftermath of any political trial, the outcome of the trial and the outcome of how we feel about it diverge dramatically. The most sympathetic account, which also has the most complete description of the trial, says that he passed between the fires unharmed—that the community had sided with him, and therefore placed the fires far enough apart that he could make it in safety. This, after all, is the secret of the ordeal: the fire, the water, the placement, the decisions on healing, all depend on how the community feels, and on sufficient communal faith in the shared experience of suffering. But in that account, the crowd in the aftermath seized him, pulled him along the ground, and injured him severely enough that he died a week later. This was from the most sympathetic account, and an eye witness one at that. One of the later accounts, the most hostile, changed the story, saying he had been burned passing through and died the next day, clearly guilty.

A trial by ordeal was not about miracles or superstition. It was, in effect, about the community making a decision on the innocence or guilt of the party, and then bringing it about. This is an irrepressibly recurring element of the rudest conception of justice across societies and time, from Socrates to John Brown. And certainly we prefer our legal system to try and be above it, as much as any system made up of human beings with all their biases, presided over by a judge with all of theirs, can be. But the Rittenhouse trial will not end next week with a verdict. It will not end when it exits the courtroom. It is a trial that was already part not only of public discourse but political discourse, something that is only ramping up. This time the mounds of fire will not signify our common understanding and consensus.

Judge Schroeder's remarks transcribed:

This is about our constitution. A thousand years ago, a case like this would have been tried. Well, let’s go back even further. Let’s go back to the—I’m sure you remember it. The fall of Rome in 476 and when Rome fell the world changed dramatically. And the ancient law which had developed from Greece and Rome which involved jury trials—not the kind of juries we have today but they were the resolution of legal disputes by the use of reason—that fell with Rome. And some very primitive methods came into use to decide legal disputes including criminal cases. Sometimes I—I saw somebody at one of my grandkids games a month or so ago and he was wearing a shirt that said demand trial by ordeal. No, demand trial by combat. And I thought what an unusual shirt. But because I talk about this once in a while I thought it was kind of interesting. I guess it turns out that there’s a program on television that deals with that does anybody familiar with that? Well there’s some program on TV that has dealt with the concept of trial by combat and I think there may be a movie coming out about that. Actually it was true a thousand years ago, that people who were having with a legal dispute including in criminal cases could either themselves or hire someone to fight for them and they’d fight with the other side physically and there’d be an ecclesiastical blessing, a priest would bless it and it was decided that God would guide the hand of the innocent and that the innocent person would win that fight and that would be the outcome of the case. They also had something called trial by ordeal. And the concept was that a person would be made to walk across for example a bed of coals, burning coals, or stick her hand or his hand into a boiling water, and depending on the healing period, if the person recovered sufficiently and this was blessed you know as so it would be a message from God, that was determined if he didn’t come out too badly he was innocent. If he did his punishments had just begun. So that’s how they actually decided cases. And then in 1215 Pope Innocent III prohibited priests from participating in these ceremonies. So um they had to turn to some other way to determine these issues and they moved back to the jury system and the initial juries were actually made up of people who knew the people involved. People who had either been witnesses who saw what happened or people who were acquainted with the people and knew whether they were honorable people whether they were violent people, whatever the case may be. They had some knowledge of the people and they’d get together and they’d talk it over and they’d come up with a verdict. Well what‘s the number one problem that you would see with a system like that? Bias.