Arena Rockin' The Vote?

Tune in to any Classic Rock radio station, or click on a Spotify playlist of rock 'n' roll anthems, and whose songs will you hear? A lot of straight, white, and often angry males: AC/DC. Lynyrd Skynyrd. Bruce Springsteen. Creedence Clearwater Revival. Black Sabbath. ZZ Top. Guns n' Roses. Bob Seger. Grand Funk Railroad. George Thorogood. Metallica. Aerosmith. Who are they mostly singing to, both on their original records and as latter-day legends? A lot of straight, white, and often angry males, most of us once party-hearty teenagers who've since become middle-aged working stiffs. Why should this particular set of artists and audiences matter today? Because this is the demographic now held to be a key voting bloc in many places, credited with or blamed for Donald Trump, Brexit, trucker blockades, and anti-vaccine rallies. From Sweet Home Alabama to the Highway to Hell, popular music and populism have significantly overlapped.

The connection seldom gets noticed. While the country sound of Nashville has long been associated with red-state politics in the US, the more varied - and commercially far more lucrative - genre of rock has had its own influence on a working- or middle-class base in many countries. It isn't so much that performers have actively backed populist causes, although Bernie Sanders used Springsteen's "We Take Care of Our Own" as a campaign theme and Skynyrd played private gigs for Republican conventioneers in 2016. Rather, it's that several generations of listeners have conflated the loud 'n' proud rebellion of electric guitar riffs with their private ideals of integrity, resilience, and rugged individualism. Call it arena rock, call it Rust Belt rock, call it blue-collar boogie, call it Golden Oldies for the Boomer and Gen X cohorts, but don't underestimate its impact. While we usually think of rock 'n' roll as the soundtrack of juvenile delinquency in the 1950s, student protest in the 1960s, and punkish irreverence in later decades, some of the medium's most vital expressions may have really been the Silent Majority's way of making some noise.

Consider acts like CCR, the meat-and-potatoes quartet whose visual and sonic style, and class-conscious hits like "Fortunate Son" and "Proud Mary," were defiant rejoinders to the self-indulgent utopianism of their psychedelic competitors; Lynyrd Skynyrd, the unrepentant American Southerners who regularly played their immortal hymns to rural independence, "Freebird" and "Simple Man," before a huge Confederate flag; Australia's AC/DC, blaring brazenly toxic masculinity avant la lettre, in "Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap," "Have a Drink On Me," "You Shook Me All Night Long," and a barroom jukebox of other outrages; heavy metal heroes Judas Priest and Iron Maiden, offering cathartic fantasies of power and freedom to underemployed youth around the world, with "Breaking the Law" and "Run to the Hills"; and superstars John Mellencamp, Bob Seger, and Bruce Springsteen, articulating the hopes and fears of a transforming global economy's newly vulnerable farmers and factory workers, via the multimillion-selling albums Scarecrow, Against the Wind, and Born In the USA. It was all mass-marketed entertainment, of course, but the continued fame of the musicians, and the enduring appeal of the music, tells us something about what really mattered - and still matters - to their constituencies. People who first encountered the songs in 1969 or 1975 or 1986 have grown up and grown old absorbing messages of group solidarity and personal honor, socially tolerant but sternly ethical, apolitical but anti-elitist, delivered by icons of nonconformity, charisma, and cool. The philosophy of rock 'n' roll may have drifted rightward over its seventy years, but the right has just as surely been rocked.

As celebrities, rock stars also anticipated the distrust of authority and expertise which we hear in right-wing reaction internationally. Often disparaged by music journalists in their day, some artists defended themselves and their followers in language that seems oddly prescient now. "The rock press was always attracted to the Talking Heads, Television, the Ramones, the New York Dolls, the Sex Pistols – bands who couldn’t sell out a stadium or even an arena," griped Gene Simmons of the greasepainted foursome Kiss. "There is a side to that media completely devoid of connection to the people who make up most of the rock audience.” Likewise, AC/DC guitarist Angus Young recalled the band's first tour of the US in 1977, "What was real strange was that although the media was pushing this really soft music, you'd get amazing numbers of people turning out to hear the harder stuff." Judas Priest singer Rob Halford had his own complaint: "You get narrow-minded critics reviewing the shows, and all they think about heavy metal is that it is just total ear-splitting, blood-curdling noise without any definition or point. This is a very, very professional style of music. It means a great deal to many millions of people. We treat heavy metal with respect."

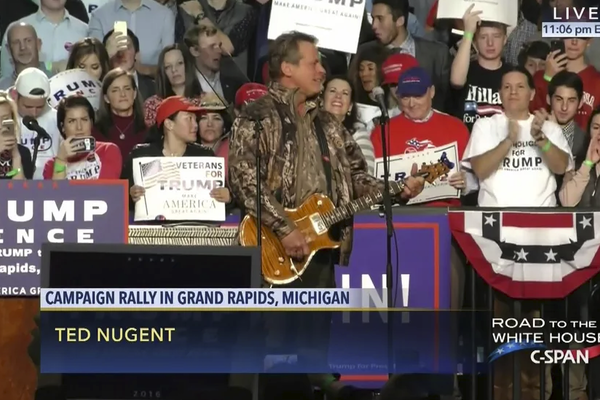

In 1970 rock promoter Frank Barsalona noted that critical approval wasn't important to the crowds flocking to see Grand Funk Railroad. "They have been put down repeatedly by the underground press but the younger kids are not letting the press tell them what to like," he said. And Ted Nugent, the Motor City Madman - nowadays a conservative provocateur best known for his leering 1970s successes like "Cat Scratch Fever" and the libertarian "Stormtroopin'" - summed up his views on the Detroit-based rock magazine Creem, declaring, "Most of its so-called writers provided me with constant fortification to my concrete understanding of how transparent, criminal, and chimplike the hippie lifestyle truly is." This disconnect between sanctioned opinion and popular sentiment, which didn't seem to matter much when it was confined to the record shops, has lately migrated to the ballot box, where it's made an historic difference.

Granted, it's difficult to trace a connection from any subcategory of pop culture directly to political insurrection, from "We're An American Band" to "Make America Great Again." But the vast populations who've matured from alienated adolescents to disaffected citizens, all the time raising fists and banging heads to heavily amplified songs about macho bluster, grassroots defiance, and stubborn allegiance to community and class, comprise much of today's populist movement, and they first gained their sense of themselves as freedom-loving challengers of an arrogant and out-of-touch establishment through a catalogue of hard-rockin' Greatest Hits.

Newer formats of hip-hop or K-pop could themselves be heralds of nascent social uprisings somewhere else on the spectrum; the confirmed sales and committed partisans of denim-clad, blues-based, guitar-playing ensembles and soloists, however, make their import obvious. Even at its economic peak, the music industry was never a monolith, yet in terms of tickets sold and units shipped, Back In Black, Born to Run, and the massed ranks of the Kiss Army enjoy a collective resonance that drowns out comparable claims for Lizzo, Harry Styles, and BTS. Whatever you think of the music, that so many have identified so deeply with it for so long bears reflection. If the Battle of Waterloo was won on the playing fields of Eton, the electoral surges of the last ten years - and perhaps of the next ten as well - may have been generated in the concert halls of Cleveland.