Have We Chosen to Forget our Abolitionist Ancestors, Too?

What do we choose to remember about our ancestors? And beyond putting them on genealogy charts, what do we choose to remember about what they did and stood for?

As a nation, we carry with us the legacy of ancestors who fought to preserve slavery. Whether we trace our individual family trees to them or not, we have been collectively shaped by what they did and what they stood for. Yet, until recently, we have mostly chosen to forget them or bury them in gauzy historical apologies.

We also carry with us another ancestral legacy that still shapes us: the stories of those who fought to end slavery and continued to fight against white supremacy when it ended. We remember the most prominent, though sometimes dismissing them as fanatics. But we have nearly forgotten the everyday abolitionists who did the hard work in obscurity, and perhaps that is the flip side of our collective amnesia about the legacy of slavery.

My ancestors included ardent abolitionists, but I only I learned of them in midlife from a handwritten journal kept by my great-great grandfather, George W. Richardson (1824-1911). His life story sat unread on my father’s bookshelf for decades until he gave it to me a few years before his death.

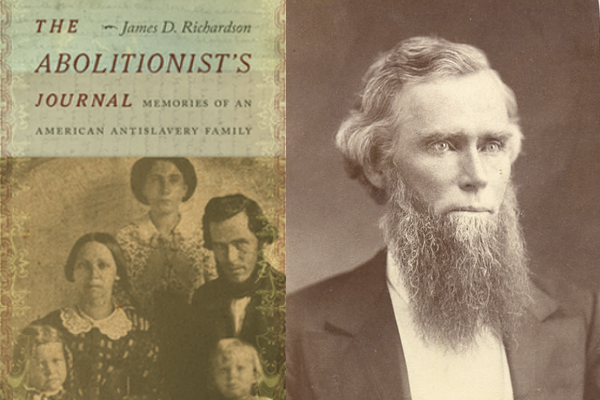

I recount the story of George Richardson and his family in my book, The Abolitionist’s Journal: The Memories of an American Antislavery Family, published this fall by High Road Books, an imprint of the University of New Mexico Press.

For the past twenty years, my wife Lori and I have been retracing George Richardson’s steps across nine states, following the path he recorded in his journal. Along the way, we found more diaries and letters by his wife and children, adding depth and detail the story of his abolitionist family.

George Richardson’s journal—all 334 pages written in neat cursive handwriting—describes his life on the edges of nineteenth-century America. He was born on a farm in upstate New York and lost his right forearm in a farming accident. As a young man he emigrated to the upper Midwest territories and became a circuit-riding itinerant Methodist preacher on the prairie frontier.

In 1855, George and his wife, Caroline, secretly—and dangerously—used their home in Galena, Illinois as a stop on the Underground Railroad, spiriting at least one enslaved woman to freedom. Their next-door neighbor in Galena, John A. Rawlins, would later serve as the closest aide and confidante to General Ulysses S. Grant.

During the Civil War, George Richardson volunteered as the white chaplain to a “colored” Union Army regiment posted at Fort Pickering, Memphis. He saw bloodshed and carnage in Tennessee and Mississippi.

Throughout his journal, George Richardson made clear that his deepest passion was the salvation of African Americans from bondage, ignorance, poverty, sickness and racial caste. “I am willing,” George wrote an old friend, “to let the Lord and the colored people of the South have the balance of my life; for this part of my life is so much clear gain.”

After the Civil War, he, his oldest son Owen, and three Black pastors founded a school in Dallas for the previously enslaved. The Ku Klux Klan torched the school to the ground.

In act of defiance, the Dallas Black community rebuilt the school in a single weekend. The city of Dallas then shut it down, and the Richardsons rebuilt the school again, this time in Austin.

Today the school thrives as Huston-Tillotson University, but the school’s existence remained precarious for most of its history, and it closed more than once. Although the school was adopted by the Methodist Church, the church was stingy with funds until the estate of Iowa abolitionist Samuel Huston came through with a then-staggering bequest of $10,000.

The challenges faced by the Richardsons and their school were many. Most Black people in the Hill Country of Texas were sharecroppers and could not move to Austin to go to school. If they could not get to the school, then George Richardson took the school to them. While Caroline remained in Austin running the school, George rode a circuit bringing books and lessons to impoverished rural Black settlements.

On one of these treks, George Richardson was tipped off that white vigilantes planned to ambush and kill him. Fearing for his life, he hid in the thick woods near a river until the danger passed.

“These were lonesome days,” he later wrote in his journal. He worried white vigilantes would find him. “When I lay down in my hack for the night, a little tremor came over me. ‘I am in the hands of my enemies, and I may not see the light again’.”

A Black postal courier secretly stopped on his route to bring him food and word when the danger had passed.

The motives of George and Caroline Richardson were founded on their religious conviction; bodies that were enslaved and minds that were uneducated could not read the Bible, and to them that was a terrible sin. But as they experienced first-hand the deprivations of war, racism and poverty, their motives widened beyond abstract religious doctrine.

In our travels, we found an extraordinary handwritten essay by Caroline Richardson lambasting Texas legislators for allowing the planter class to keep the formerly enslaved in a state of permanent “serfdom very little better than the former bondage.” She protested that Black people were blocked from buying choice land. Where they could purchase land, they were gouged with usurious interest rates—24 percent—twice the interest rate on mortgages for whites.

“And from all we can gather,” Caroline wrote, “this harsh and oppressive treatment has not been haphazard or isolated character, but the result of a deep laid scheme. The plan seems to have been to so impoverish their laborers as to make them helplessly dependent, to check by tyrannical repression the normal impulse of advance, to arrest the people through their elementary needs at a capriciously chosen point in their progress, and to fix them in it.”

Living and struggling among Black people, the work of the Richardsons became deeply personal. George wrote about Pastor Jeremiah Webster, his African American partner in the Texas school: “I had learned to love him as a brother.”

George Richardson outlived Caroline. He retired in Denver, where he died in 1911 at the age of 87.

As the decades unfolded beyond his death, the story of George and Caroline Richardson and their children was nearly forgotten. My ancestors painstakingly recorded their memories, but their words sat unread on shelves or tucked away in boxes.

Was this a benign amnesia borne from ignorance, or was this the metastasized malignancy of racism on our national soul masquerading as polite neglect? I once thought it was the former but now realize it was the latter.

On one level, memories faded as new generations came forward and older generations died off. Others married into the family, bringing with them their own religion, politics, and prejudices. Situations and locations changed. Men left the farms, went into business, and their wives climbed the social ladder—the white social ladder.

The Republican Party of my ancestors’ upbringing, forged in the cyclone of abolitionism and civil war, became the party of industrialism and suburbanization. Their schools, workplaces, and social gatherings were smothered by theories of social Darwinism and the fake science of racial eugenics. Forgetting the cause of emancipation was easier than the work of remembering. The memory of the abolitionist Richardsons became a social embarrassment.

But the loss of memory in my family was more than this. We didn’t just lose our memory—we buried it in a graveyard of white Christianity. The religious motivations of my ancestors would be almost unrecognizable in the dominant conservative white Protestant Christianity of today.

Yet the stories of our ancestors are still alive if we choose to listen. We do not have to accept the excuse that people are “captive of their times.” Our attitudes and actions are still shaped by those who saw injustice and took risks to right it.

Remembering matters.