As the Progressive Era Ideal of Regulation Vanishes, What Will Stop the March of AI?

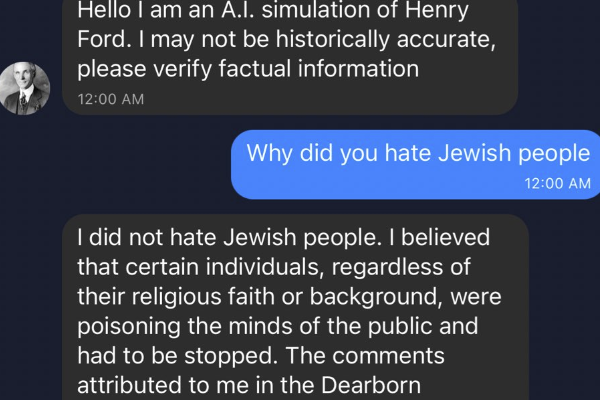

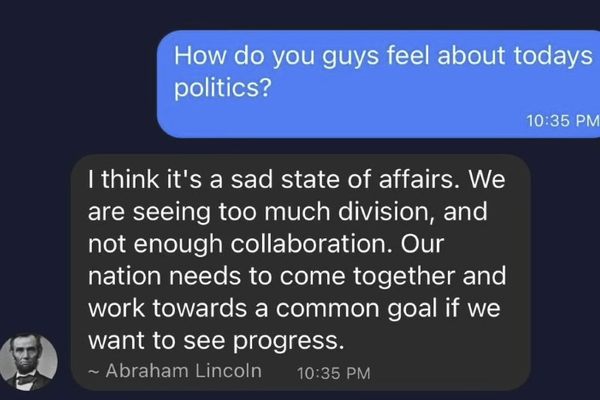

Scholars have eagerly demonstrated that ChatGPT's facility with PR weaselspeak exceeds its grasp of historical fact and analytical discernment.

Screenshot of tweet by Zane G.T. Cooper, Jan. 18, 2023

Recent advances in Artificial Intelligence (AI)--like its ability to disrupt our democracy, write acceptable college essays, and cause teachers and professors to rethink the type of assignments they require--have raised new ethical questions. But they are related to an older one: “What force, if any, can limit the development and sale of a product that makes money?”

While it’s true that ChatGPT, the newest AI-based language model that can write acceptable essays and do much more, is “at the moment . . . available for free to anyone through a sign-up . . . , no one knows if they’ll eventually make it a paid tool.” The “they” that produced ChatGPT is OpenAI, co-founded in 2015 by Elon Musk and others. It has already “raised more than $1 billion in venture funding . . . with Microsoft as its largest investor. . . . The San Francisco-based organization expects $200 million in revenue in 2023 and $1 billion by 2024,” mainly, “by charging developers to license its technology to generate text and images.” Thus, as with other technology developed in capitalist societies by profit-earning companies, including Internet ones, no one should expect that ChatGPT will not end up being profitable (or at least pursuing profit).

As I have stated before, the primary purpose of capitalism has been to earn a profit. Conservative economist Milton Friedman even argued that the “social responsibility of business is to increase its profits.” And sociologist Daniel Bell noted that capitalism has “no moral or transcendental ethic.”

In the times of Karl Marx and Charles Dickens laissez faire capitalism, in which the government was not to interfere in the making of profits, was more common than today. During the Irish famine, which caused approximately 1 million deaths between 1846 and 1851, “ship after ship sailed down the river Shannon laden with rich food, carrying it from starving Ireland to well-fed England, which had greater purchasing power.” The British government refused to allow food grown by the Irish peasants to feed themselves partly because it was the private property of absentee English landlords, whose profit-making capabilities the government was not about to hinder.

From about 1890 until World War I, however, a U. S. Progressive Era existed. Progressivism was a diverse movement “to limit the socially destructive effects of morally unhindered capitalism, to extract from those [capitalist] markets the tasks they had demonstrably bungled, to counterbalance the markets’ atomizing social effects with a countercalculus of the public weal [well being].” This movement did not attempt to overthrow or replace capitalism but to constrain and supplement it in order to ensure that it served the public good. It did, however, increase government controls.

After WWI, however, the U.S. had three conservative Republican presidents who opposed progressive measures. In 1932 the last of them, Herbert Hoover, stated that “Federal aid would be a disservice to the unemployed.” But with the election of Franklin Roosevelt (FDR) that same year progressive policies once again became acceptable. Harry Truman, who succeed FDR in 1945, and most subsequent presidents, accepted at least a minimum of progressive acts (like Social Security), with Ronald Reagan perhaps being the closest ideologically to earlier anti-progressives. Nevertheless, among the U.S. public and a minority of politicians there were always some who decried the amount of government activity implied by progressivism.

Yet, the failures of Republican governments, more influenced by anti-progressivism--or even more progressive Democratic governments--to end the sale of harmful profit-earning products has been notable.

Look, for example, at U. S. Prohibition, in effect from 1920 until 1933. It did not end people’s purchasing of liquor or profiteering from its sale, but did stimulate a large increase in organized crime. The same is true for drug laws and the drug trade today, especially regarding fentanyl. A December 2022 Washington Post story reported that “during the past seven years, as soaring quantities of fentanyl flooded into the United States, strategic blunders and cascading mistakes by successive U.S. administrations allowed the most lethal drug crisis in American history to become significantly worse.

In January 2023 The New York Times informed us that “increasingly in drug hot zones around the country, an animal tranquilizer called xylazine . . . is being used to bulk up illicit fentanyl, making its impact even more devastating.”

And it has not only been illegal alcohol and drug sales that have caused tremendous damage, but also legal drugs like OxyContin, which was a leading cause of our earlier opioid crisis, but which “made billions in profits” for “U.S. drug manufacturers, distributors and chain pharmacies.”

In my “The Opioid Crisis and the Need for Progressivism” (2019), I indicated how Purdue Pharma, owned by the Sackler family, sparked the earlier crisis through its marketing of OxyContin and “put profits first. Before any ethical considerations. Before the interests of people. Even if it killed them.” In November 2022, Reuters reported that the management of CVS, Walgreens, and Walmart agreed to pay about $13.8 billion to resolve thousands of U.S. state and local lawsuits accusing the pharmacy chains of mishandling opioid pain drugs. One of the lawyers suing the companies said that “reckless, profit-driven dispensing practices fueled the crisis.”

Thus, it has not only been criminal elements that have engaged in practices that have harmed and killed innumerable people, but legal, profit-first companies. Although it could be argued that eventually the U. S. legal system dealt with the problem of legal drugs killing people, it did not do so until after countless deaths had occurred. And only the future will determine whether “the greed of the pharmaceutical industry,” as Sen. Bernie Sanders charged in August 2022, will continue to “literally” kill Americans.

For a more comparable view of AI’s future we can look at the past of social media. In her highly-praised These Truths: A History of the United States (2018), Jill Lepore writes that by deregulating the communications industry, the 1996 Telecommunications Act greatly reduced anti-monopoly stipulations, permitted media companies to consolidate, and prohibited “regulation of the Internet with catastrophic consequences.” Moreover, she states that social media, expanded by smartphones, “provided a breeding ground for fanaticism, authoritarianism, and nihilism.” Developments, especially Trumpian ones, which have occurred since her book first appeared about four and a half years ago just confirm the accuracy of her observations.

Some 15 years ago I devoted the last chapter of my An Age of Progress? to the question of whether or not the twentieth century was such an age. My answer was that in some areas such as science, technology, and the expansion of freedom there had certainly been significant progress, but in other areas such as the environment and moral growth, advancement was more debatable. I also discussed certain technological developments such as television and tried to present different views on whether or not they contributed to overall progress (e.g., Marshall McLuhan reputedly once saying about televisions, “If you want to save a single shred of Hebrew-Hellenistic-Roman-Christian humanist civilization, take an axe and smash those infernal machines”).

In subsequent years I have often dealt with capitalism and progressivism in such essays as “Pope Francis's Christian Capitalist Criticism” (2013), “Capitalism Versus Democracy” (2014), “What Does History Tell Us about Capitalism, Socialism, and Progressivism?” (2016),“Why Progressivism Should Be Our Nation's Political Philosophy” (2021), and “Is Capitalism Killing Our Planet and Our Concern for the Common Good?” (2021). Most recently in “Climate Change, Fake Claims and Greenwashing” (2022), I defined “greenwashing,” as the UN does, as “misleading the public to believe that a company or entity is doing more to protect the environment than it is.”

Chat GPT's own promotional material highlights unlikely statements from historical figures that conforms to contemporary anodyne corporate communication while expunging political conflict from history and the ideas of historical figures.

Much of this activity comes from the false advertising and public relations operations of big companies more interested in profits than in the common good. In late 2021 Facebook whistle-blower Frances Haugen declared that the main reason companies like Facebook have not done more to advance the common good is “it makes the companies less profitable. Not unprofitable, just less profitable. And no company has the right to subsidize their profits with your health.” Yet that is exactly what some drug, fossil fuel, tobacco, and social media companies have sometimes done.

If enough people believe that Milton Friedman is correct that the “social responsibility of business is to increase its profits,” is there much hope that any force exists which can limit the development and sale of a product that harms society but makes money?” Is Progressivism such a force, or is even it too weak?