No Golden Anniversary for the Paris Peace Accords

The last days of January will mark the passage of 50 years since the United States and North Vietnam concluded the Paris peace agreement that was supposed to, but did not, end the bloodshed in Vietnam.

The exact date to be commemorated, though, depends on where you are (or were). On the clocks in Washington, D.C., the agreement officially went into effect on the evening of January 27, 1973. That was also the date in Paris when the document was ceremonially signed, as noted in the final paragraph of text above the signatures. But it was already the next day in Vietnam, where I observed the first hours and many more months of continued fighting as both Vietnamese sides ignored the agreement’s ceasefire clause. So the date that remains etched in my memory 50 years later is the 28th of January, not the 27th.

Writing this, it strikes me that the difference in those dates is not just numerical but symbolic, a telling metaphor for the wide gap between Washington’s vision of reality and the true situation in Vietnam.

Here (with some abridgements) is a passage from my book Without Honor: Defeat in Vietnam and Cambodia recounting what I saw and heard in the minutes before and after 8 o’clock that morning, Saigon time, the hour fixed in the agreement for "the complete cessation of hostilities" throughout South Vietnam:

Fifteen minutes before the ceasefire, the rhythmic chug of a machinegun sounded from just beyond the palm-shaded houses and open-fronted shops of a hamlet called Chanh Hiep, which sat on the shoulder of the highway eighteen miles north of Saigon. Over the sound of machinegun fire came the higher-pitched, more rapid bursts of the government militia's American-supplied M-16 rifles and the answering slap of Communist AK-47s from farther out across the village rice fields. From the sound of the firing, the attacking force was small—no more than a squad, perhaps. The Communist command, as it had also done when a ceasefire was anticipated the previous October, had split its army into small bands and ordered them to penetrate all the villages they could reach, in the hope they could remain until their presence was legalized by international truce-observer teams.

The battle of Chanh Hiep had begun at three o'clock that morning, when a Communist loudspeaker called out of the darkness advising the hamlet's defenders to put down their weapons rather than risk dying in the war's last hours. Instead, the militiamen opened fire and traded shots for the rest of the night with the attackers. Now, the villagers stood or crouched in their doorways. They were afraid, with the fighting so near. But to leave would risk having their homes looted by government soldiers: they would not do so unless the hamlet itself came under fire. As eight o'clock approached, those who wore watches kept glancing at their wrists. Not much showed in their faces. It was as if they were wondering, but not really able to believe the firing would actually stop.

… Groups of soldiers stood in the village street: not infantry, but cadets from the South Vietnamese army's engineering school. Like many thousands of others plucked from noncombat duties that weekend, they had been handed rifles instead of textbooks and sent to the field, where the Saigon command wanted every available soldier to meet the expected pre-ceasefire attacks. You could tell, looking at them, that the cadets were inexperienced and frightened. They kept looking anxiously toward the firing, where combat soldiers would have hardly turned their heads. One of them had a cheap portable radio and as the ceasefire hour neared, the others clustered around him, waiting for the time signal.

When it came, there was no pause in the rifle and machinegun fire nearby. The farther-away thump of artillery did not stop either.

Precisely at the stroke of eight o'clock the radio began broadcasting a speech by Nguyen Van Thieu, South Vietnam's wartime president, to whom the Paris agreement meant not peace for Vietnam but only abandonment by the United States. For three months he had resisted signing, until his American ally threatened to sign without him and to shut off the aid that kept his army in the field. But though he had finally consented to the agreement, none of Thieu's misgivings had truly been allayed. Just because "peace" is mentioned in the agreement, he was saying now on the radio, it does not mean that Vietnam will really have peace.

We stood in the dusty street and listened to Thieu's voice and to the undiminished gunfire and watched the hands of our watches crawl past one minute after another…. More minutes went by. A sergeant, not one of the cadets but an infantryman who paused on his way to rejoin his own unit farther on up the road, turned abruptly away from the radio and looked across the street, where the villagers now stood unsmiling and tense. No one was looking at watches any more. "The president can say anything," the sergeant said bitterly, "but this war will never end."

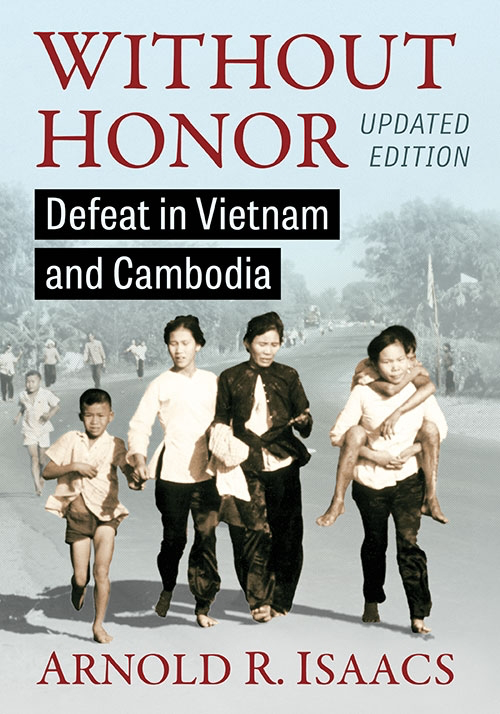

An hour later, I stood with my good friend and fellow correspondent Larry Green, then with the Chicago Daily News, on the outskirts of another roadside hamlet named Tuong Hoa, a few miles from Chanh Hiep. Rifle fire and grenades sounded among the houses just ahead of us, while South Vietnamese artillery rounds swooshed overhead every ten seconds before falling into the village. During a brief lull in the gunfire, a woman appeared on the road, jogging clumsily toward us. Clinging to her back was a wailing child bleeding from shrapnel wounds in both buttocks. Behind them came more villagers, running at first, then slowing to a plod, carrying cooking pots or cloth parcels of possessions in their arms or on their heads. As they approached the spot where we were standing, Larry lifted his camera and took the photograph that appears on the cover of the new edition of my book. Larry is still a friend, and that scene on the road from Tuong Hoa is still vivid in my memory, so that cover has very special meaning for me.

Shortly after the women came past us, two government soldiers came running from among the houses, carrying a dead or badly wounded comrade. They were followed by an entire company, “running half-crouched,” I wrote in my book, “each man stamped into the same classic image of fear and flight, rifle gripped in one hand, helmet clamped on with the other.” As they neared, a flurry of shots from Communist troops crackled over our heads, and Larry and I jogged back down the road.

Battles just like the ones we saw in those two hamlets were occurring at the same time in hundreds of other places where small Communist units penetrated villages or blocked roads in the last hours before a “ceasefire in place” would supposedly leave them in control.

“Place” was a murky concept in a war where a lot of territory was not clearly held by either army. But in and around populated areas and along major transportation routes, most areas were predominantly controlled by one side or the other, even if opposing troops might penetrate a particular spot for a for a few hours or days. Before the peace agreement was signed, Gen. Fred Weyand, the last commander of U.S. forces in Vietnam, urged Henry Kissinger and his negotiating team to push for the two Vietnamese sides to exchange list of military units and their strength and locations, so there would be some kind of record of where each side’s forces claimed to be before a ceasefire happened. I don’t know what kind of attention Weyand’s suggestion got or didn’t get in Washington, but am not aware of any evidence that such a plan was ever seriously offered in Paris. It’s extremely unlikely that either Vietnamese side would have accepted that procedure anyway. So in the end, the word “place” was completely undefined when the “ceasefire in place” was supposed to take effect.

If the lines had really frozen at 8 o’clock that morning, Communist troops would have blocked all the major highways radiating out from Saigon and would have occupied large parts of various provincial and district capitals and other areas in normally government-held territory. Those penetrations came before the ceasefire hour so technically did not violate the letter of the peace agreement. But they unquestionably violated its spirit, the principle that the fighting would end with both sides at least roughly remaining on the ground they normally controlled. In contrast, the South Vietnamese counteroffensive to retake population centers and reopen major roads continued for weeks after January 28, so were unequivocally violations of the ceasefire. But observing the letter of the agreement would have accepted a situation grotesquely different from the true military balance. That would have been blatantly against the agreement’s basic premise. So realistically, if not technically, the Communist attacks before the ceasefire, not South Vietnam’s counterattacks after it, were the crucial violation in that initial phase.

Subsequently, though, that moral argument was reversed. After a month or two of heavy fighting, battle lines around the country were more or less back where they had been before the Paris agreement was concluded. If Thieu had stopped or cut back offensive operations at that point, we can’t be sure, but the Communists might have dialed down the fighting too; they had taken heavy casualties and might have welcomed an opportunity for their troops to rest and recuperate. But that option did not appear. Instead of giving peace a chance, the South Vietnamese took the opposite course, keeping their forces on an all-out offensive and continuing to wage full-scale war for many more months while the agreement faded into a meaningless memory. The Saigon government’s decisions and actions in the spring of 1973 turned the blame argument around. If the Communist side was primarily responsible for breaking the ceasefire in its first hours and days, by the same letter-vs-spirit test Saigon was far more at fault for the continued fighting later on.

Lastly, I am not aware of any evidence that the United States ever made any meaningful effort to get South Vietnam to rein in its post-Paris offensive and perhaps retrieve some semblance of a truce. Instead, once U.S. war prisoners were safely back home, the Americans consistently backed Thieu’s policies and provided essential support for his continuing war. So the U.S., too shares significant blame for turning the promise of peace in the Paris agreement into empty words.

The underlying reason for the agreement’s failure was that the two Vietnamese sides had completely unreconcilable visions of their country and its future. Both held a fundamental belief that the other side had no right to exist, much less to any role in a postwar regime. Neither side ever abandoned the goal of total military victory, and the U.S. never used its leverage to moderate its ally’s policies. The inescapable conclusion is that all three were to blame for the Paris agreement’s lack of any result beyond the single accomplishment of ending the American war, which would almost certainly have ended anyway. The agreement did not end or reduce the violence or bring any relief to the Vietnamese or Lao or Cambodians who would suffer for another two-plus years until the Communist victories in 1975. That outcome, achieved exclusively by force of arms and not through any peace process or any form of national reconciliation, rendered the final verdict that stands just as clearly 50 years later: the Paris agreement was an utter and tragic failure, for which all the signers were to blame.