"Class War" is Back in the Headlines. But What is it, Really?

Communards at a Barricade, Paris 1871

Ours will go down as the age of class war. We talk about it all the time, and with mounting urgency amidst the realities of economic crisis, ecological catastrophe, and social declension. Rising inequality and the ever-increasing stakes of our brutal economic divide are constant reminders of this conflict, as is the ongoing wave of strikes, with workers of all kinds demanding higher wages and better conditions.

Barely a day goes by now without class war featuring in one headline or another. For British economist Ann Pettifor, the finance sector’s response to spiraling inflation – raising rents, crushing demand, and disciplining workers – is clear evidence of “their effective preference is for class war over financial stability.” Pettifor’s formulation, which has been republished all throughout the bourgeois press, is just one of many similar usages of this phrase in 2023 alone.

And yet, despite a collective willingness to acknowledge the existence of class war, to use this phrase as a popular trope and a technical term, we don’t really know what it is. As one of history’s most prominent narrative categories, class war wants for critical explanation. So: what is class war?

Within critical thought, class war is used less as a technical term and more as an affective catalyst, reframing actions and rhetoric through military concepts and language, without offering so much as a program or practical strategy. That is what we encounter most famously with Marx and Engels, when in 1848 they summarized the development of the proletariat and the bourgeoisie: the “fight” between the classes has become so absolute that class struggle (Klassenkampf) modulates into civil war (Bürgerkrieg) and then open revolution. From this perspective, the work of politics is to undertake the transition from one phase to the other, from the grinding brutality of class struggle to the presumably intentional, organized, and openly violent confrontation with the bourgeois and their institutions.

In other words, revolution means to see the exploited class waging war against the economic regime and interstate system that maintains its exploitation, namely capitalism, whose beneficiaries will militarily defend their benefits with everything they have. To speak of class war might therefore be to conjure militancy and solidarity against the present state of things. And in this sense, class war is not just the stuff of political discourse; it emanates from the lived experience of social conditions.

The first ever recorded utterance of the phrase “class warfare” is from January 25, 1840, when it appeared in the Chartist newspaper the Northern Star. Chartism was a movement of redress that openly sought political enfranchisement. By the same token, however, the movement also comprised a militant faction for which actual warfare was seen to underwrite more peaceable demands. The invocation of class war came at the end of an article setting out the movement’s positions and demands, which pronounces ritual bloodletting as the outcome of underrepresentation coupled with immiseration. “Good must come to the nation out of this class warfare for pre-eminence,” it reads, “as from a compound of the most deadly poisons a wholesale medicine may be extracted.” No longer a threat, something to be worried about in the future, but alive and deadly, here and now: the class struggle had already erupted into civil war.

This usage of class war is carried on all throughout the history of social movements, into the twentieth century and beyond. It is what Rosa Luxemburg once described, against the beating drums of national chauvinism and the opening up of an imperial war of extermination, as “the crux of the matter, the Gordian knot of proletarian politics and its long term future,” namely the need to escalate the ongoing class struggle into actual civil war. “The proletariat does not lack for postulates, prognoses, slogans,” she says. “It lacks deeds, the capacity for effective resistance to imperialism at the decisive moment, to intervene against it during the war and to convert the old slogan ‘war against war’ into practice.”

Other well-known revolutionaries would hold to a similar line. For Lenin, thinking about the Paris Commune of 1871, the proletariat “must never forget that in certain conditions the class struggle assumes the form of armed conflict and civil war; there are times when the interests of the proletariat call for ruthless extermination of its enemies in open armed clashes.” Or for Mao, civil war marks the passage from contradiction into antagonism, or mobilization of masses. In his view, “the contradiction between the exploiting and the exploited classes” has persisted through slave society, feudal society, and into modern capitalism as a “struggle” between the two; “but it is not until the contradiction between the two classes develops to a certain stage that it assumes the form of open antagonism and develops into revolution. The same holds,” he adds, “for the transformation of peace into war in class society.”

When revolutionaries talk about class war they tend to do so in a hybrid future-present tense: class war is coming, but it’s also already upon us. Battlefronts are opening up, but something else is looming on the horizon. Specifically: the revolutionary invocation of class war raises consciousness of the former struggle as a point of departure into the latter conflict. It seeks to recruit and to motivate comrades from a state of contradiction into acts of antagonism. The proclamation of class war is what linguists might describe as a speech act: a performative utterance that, when said, is also a kind of action – like, for instance, a formal declaration of war, which not only announces but also commences.

This is just one shared feature that links the writing of Ann Pettifor and any number of other mainstream headlines to the formulations of Marx, Engels, Luxemburg, Lenin, Mao, and the social movements they all represent.

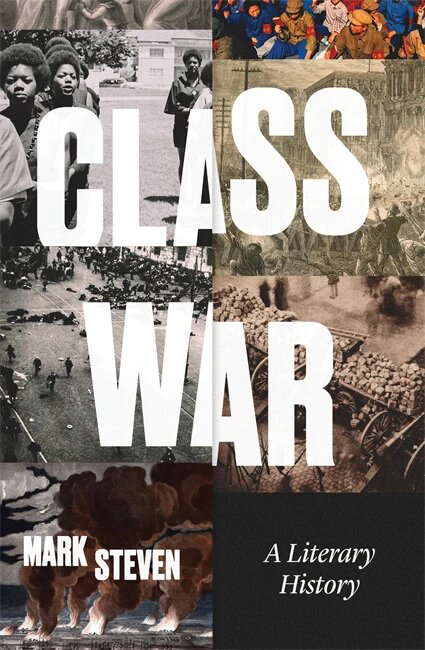

Class war is a red thread that conjoins our present moment with a submerged history of revolution. My new book, Class War: A Literary History, traces that thread, and in doing so tells a narrative that spans the globe and more than two centuries of history, from the Haitian Revolution to the Russo-Ukrainian War.