Can We Learn from Previous Generations of Historians Negotiating Between Past and Present?

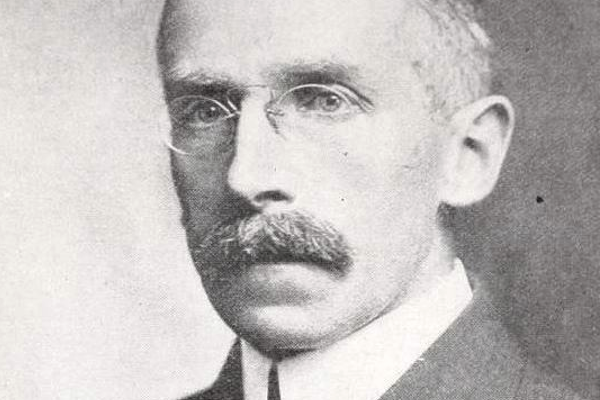

James Harvey Robinson contributed to the "New History" movement with a 1911 essay of the same name. Photo c. 1922.

Many causes and campaigns these days are looking to history to buttress their arguments. Some involve political positions, others relate to gender and racial issues, while still others pertain to broader themes of income inequality or social justice. Should historians join these causes as advocates? If not, should they write and present history in such a way that its relevance and applicability to current issues becomes clear?

We sometimes think of this as a new dilemma (or opportunity) for historians, but actually it has a history of its own. Looking into that history might help us get and keep our bearings at this time of heated public discussion. A useful place to look would be the so-called “new history” which emerged in the early 20th century. These historians espoused strategies that would draw on a wider array of historical evidence than historians had used in the past. It would place more emphasis on social and economic trends, provide more coverage of the lives of ordinary people in history, draw on allied social sciences such as economics and sociology, and dovetail with the emerging field of social studies. It would demonstrate the relevance of history for providing insights into contemporary affairs and problems. Nineteenth century history had been mostly a placid and slow-to-change field. The “new history” would liven things up.

That would be a tall order for historians. But, done well, it would permit historians from a lofty perspective to point out the historical origins of contemporary public issues and show parallels with past developments. Through teaching and writing good history, they could contribute to the public good without having to go further and also become advocates (unless they wanted to do that.)

Columbia University history professor James Harvey Robinson (1863-1936) led the way in his highly influential 1911 essay "The New History" in Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society.

Robinson made a number of points.

Historians need to be engaging, but it is hard to compete with fiction writers.

“History is not infrequently still defined as a record of past events and the public still expects from the historian a story of the past. But the conscientious historian has come to realize that he cannot aspire to be a good story teller for the simple reason that if he tells no more than he has good reasons for believing to be true his story is usually very fragmentary and uncertain. Fiction and drama are perfectly free to conceive and adjust detail so as to meet the demands of art, but the historian should always be conscious of the rigid limitations placed upon him. If he confines himself to an honest and critical statement of a series of events as described in his sources it is usually too deficient in vivid authentic detail to make a presentable story.”

What counts a good deal is the light that history casts on contemporary conditions.

“It is his [the historian’s] business to make those contributions to our general understanding of mankind in the past which his training in the investigation of the records of past human events especially fit him to make. He esteems the events he finds recorded not for their dramatic interest but for the light that they cast on the normal and prevalent conditions which gave rise to them. It makes no difference how dry a chronicle may be if the occurrences that it reports can be brought into some assignable relation with the more or less permanent habits of a particular people or person….”

Historians need to show how history can “explain our lives.”

“History is then not fixed but reducible to outlines and formulas but it is ever-changing, and it will, if we will permit it, illuminate and explain our lives as nothing else can do. For our lives are made up almost altogether of the past and each age should feel free to select from the annals of the past those matters which have a bearing on the matters it has specially at heart.”

Less relevant history might be accorded a lower priority.

“If we test our personal knowledge of history by its usefulness to us, in giving us a better grasp on the present and a clearer notion of our place in the development of mankind, we shall perceive forthwith that a great part of what we have learned from historical works has entirely escaped our memory, for the simple reason that we never had the least excuse for recollecting it. The career of Ethered the Unready, the battle of Poitiers, and the negotiations leading to the treaty of Nimwegen are for most of us forgotten formulae, no more helpful, except in a remote contingency, than the logarithm of the number 57.”

Robinson was joined by a cadre of other historians, most notably Charles A. Beard, his Columbia colleague, whose 1913 book An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States contended that the nation’s founders were motivated in part by personal financial considerations and that the Constitution was designed to protect vested interests. That dovetailed well with progressive reformers’ campaigns to reign in those interest through legislation and regulation.

Robinson in effect took his own advice. He was an advocate in the limited sense that he tried to exhort historian colleagues to become more relevant and proactive. But he mostly steered clear of the political controversies of the day himself while writing several well-received books, including some best-selling texts. But he and Beard chafed at restrictions on academic freedom at Columbia and, in 1919, left to join other progressives in founding The New School for Social Research which soon became a beacon of progressive thought in history and other fields.

The ideas that Robinson kicked off were also soon espoused by other historians. Historian Carl Becker, in his provocative 1931 American Historical Association presidential address, "Everyman His Own Historian," put a new twist on Robinson’s idea. “History is the memory of things said and done,” he said, “an imaginative reconstruction of vanished events,” which each of us…. fashions out of his individual experience.” That went well beyond what Robinson had in mind, but it extended his implicit point about taking history to the people. The Society of American Archivists, formed in 1936, took up the mantle of historical records preservation. Establishment of the American Association for State and Local History in 1940 helped with Robinson’s recommendation for more exploration of local history and sources.

In 1939, he gave something of a valedictory in his American Historical Association presidential address, "Newer Ways of Historians". He conceded that even historians like himself, using the methods of the “new history” to gain some predictive insight, did not foresee World War I, the communist revolution in Russia, the great depression, and some other recent developments. But he insisted he had been right on point back in 1911.

“[H]istory at its best needs not simply to be authentic. Its value, as a contribution to wisdom, depends on the selection we make from the recorded occurrences and institutions of the past, and our presentation of them…. Never before has the historical writer been in a position so favorable as now for bringing the past into such intimate relations with the present that they shall seem one, and shall flow and merge into our own personal history.”

Was Robinson right? He certainly ignored a great deal and rather astonishingly seems to have left women mostly out of consideration. He did not offer a definite way to measure the impact and influence of history. He later seemed to backtrack a bit or at least pursue a different course, particularly in his 1921 book The Mind in the Making, which proposed that educational institutions and historians approach social problems with a more progressive intent of creating a just social order. In The Human Comedy As Devised and Directed by Mankind Itself, a posthumous collection of essays published in 1937, Robinson seemed to blend pessimism and optimism – humans have made progress over the years but seemed to carry an ancient warring spirit. The “new history” gradually gave way to other interpretations, and the process of reinterpreting history continues today.

Some historians these days seem to go beyond a semblance of objectivity in the way they present history and assert that their interpretation must be the right one. Others are more measured, presenting fresh perspectives on the story of America in well-documented, objective works. Their work is refreshing and revealing. They are closer in spirit to Robinson, whose work is something of a model of moderate, measured, well-considered presentation that demonstrates the relevance of history in people’s lives.