Daniel Pipes: Nike and 9-11

Five years after the attacks of September 11, 2001, it is clear how terrorism has set back the cause of radical Islam.

The horrors of 9/11 alarmed Americans and fouled the quiet but deadly efforts of lawful Islamists working to subvert the country from within. They no longer can replicate their pre-9/11 successes. This fits an ironic pattern whereby terrorism usually (but not always) obstructs the advance of radical Islam. For an illustration of this change, consider an example from radical Islam's halcyon days in the late 1990s – how a prominent Islamist organization, the Council on American-Islamic Relations, easily humiliated the giant manufacturer of athletic gear, Nike, Inc.

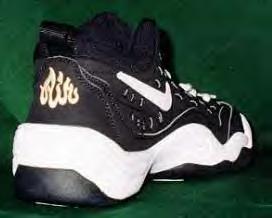

Nike had introduced its "Air" line of basketball shoes in 1996 with a stylized, flame-like logo of the word Air on the shoe's backside and sole. When the elders at CAIR nonsensically declared that this logo could "be in terpreted" as the Arabic-script spelling of Allah, Nike initially protested its innocence. But by June 1997, it had accepted multiple measures to ingratiate itself with the council. It:

- "apologized to the Islamic community for any unintentional offense to their sensibilities";

- "implemented a global recall" of certain samples;

- "diverted shipments of the commercial products in question from ‘sensitive' markets";

- "discontinued all models with the offending logo";

- "implemented organizational changes to their design department to tighten scrutiny of logo design";

- promised to work with CAIR "to identify Muslim design resources for future reference";

- took "measures to raise their internal understanding of Islamic issues";

- donated $50,000 for a playground at an Islamic school;

- recalled about 38,000 shoes and had the offending logo sanded off.

The offending Nike shoe logo, where "Air" supposedly looks like "Allah" in Arabic script.

Giving up all pretense of dignity, the company reported that "CAIR is satisfied that no deliberate offense to the Islamic community was intended" by the logo.

The executive director of CAIR, Nihad Awad, arrogantly responded that, had a settlement not been reached, his organization would have called for a global boycott of Nike products. A spokesman for the group, Ibrahim Hooper, crowed about the settlement: "We see it as a victory. It shows that the Muslim community is growing and becoming stronger in the United States. It shows that our voices are being heard."

Emboldened by this success, Mr. Awad traveled to the headquarters of the World Assembly of Muslim Youth, a Wahhabi organization in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, one year later to announce that Nike had not lived up to its commitment. He flayed the firm for not recalling the full run of more than 800,000 pairs of shoes and for covering the Air logo with only a thin patch and red paint, rather than removing it completely. "The patch can easily be worn out with regular use of the shoe," he complained. Turning up the pressure, Mr. Awad proclaimed a campaign "against Nike products worldwide."

Nike again capitulated, announcing an agreement in November 1998 on "the method used to remove the design and the continued appearance of shoes in stores worldwide." It coughed up more funding for sports facilities at five Islamic schools and for sponsorship of Muslim community events, and donated Nike products to Islamic charitable groups. The trade press also suggested a financial contribution to CAIR.

Today, all this is distant history. CAIR still can bully major corporations, as it did in 2005 with the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, but it can no longer shake them down for cash, nor can it ride a bogus issue like Air = Allah. The public is somewhat more skeptical (though not always enough so).

Successes like the Nike capitulation inspired an Islamist triumphalism pre-9/11. One apologist, Richard H. Curtiss, captured its flavor in September 1999, when he called a decision by Burger King to shut a franchised restaurant in a Jewish town on the West Bank, Ma'aleh Adumim, "the battle of Burger King." He hyperbolically compared it "to the battle of Badr in 624 A.D., which was the first victory of the vastly outnumbered Islamic community."

Portraying a trivial lobbying success as similar to a world-shaking battlefield victory provides an insight into Islamist confidence pre-9/11. No less suggestively, Mr. Curtiss wrongly predicted that American Muslims would, "within the next 5 or 10 years," go on to win more such battles. Instead, terrorists seized the initiative, relegating lawful Islamists mostly to fighting defensive skirmishes. Thus did mass violence, paradoxically, seriously impede the Islamist agenda in America.