Thomas S. Mullaney: The Chinese Typewriter

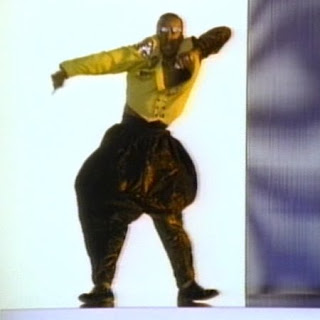

Propelled to international stardom by his multi-platinum single “U Can’t Touch This,” MC Hammer is perhaps not the first person one thinks of when studying Western stereotypes about China. Remarkably, however, the music video accompanying his 1990 hit featured one bit of fancy footwork that has helped perpetuate a distorted view of China dating back more than one hundred years. Known as the “Chinese typewriter,” the dance features MC Hammer side-stepping in rapid, frenetic movements, choreography that would gain immense popularity to become one of the defining dances of the early nineties.

Why the Chinese Typewriter? Hammer’s dance, the idea went, was supposed to mimic the alien virtuosity of a Chinese typist as he navigates what Hammer assu med must be an absurdly massive keyboard crowded with tens of thousands of characters.

med must be an absurdly massive keyboard crowded with tens of thousands of characters.

Whereas the Oakland-born artist may be credited with bringing parachute pants into mainstream culture, the same cannot be said of his ideas regarding our Pacific neighbor. The Chinese typewriter has been an object of ridicule in the West since its inception at the turn of the century.

For over a hundred years, writers in the United States and Europe have derived a unique sense of cultural and technological superiority by portraying the apparatus as absurdly large, painfully slow, and prohibitively complex.

Others have simply assumed that the machine never existed—that it is a mechanical impossibility, and thus, that China is incapable of reaching a level of modernity equal to the West for the simple reason that Chinese characters are inherently incompatible with modern technology.

Contrary to media representations, however, the past century has witnessed the development of nearly five dozen different models of Chinese typewriter, each one representing an ever more sophisticated attempt at solving a puzzle that makes the more familiar QWERTY typewriter look like child’s play: the puzzle of how to fit a non-alphabetic language containing tens of thousands of characters on an apparatus of a manageable size and a user-friendly design. Despite the complexity of this challenge and the brilliance of the solutions devised, it seems that the West has remained incapable of taking the Chinese typewriter seriously.

Two of the earliest known Chinese typewriters were designed around the turn of the century, one by a Chinese man living in the United States and the other by an American man living in China.

The first of these was operated in San Francisco Chinatown, and was based on a variation of the longstanding practice of Chinese typesetting. Encompassing roughly five thousand of the language’s most frequently used characters, the machine incorporated a large, flat tray upon which metal typeface were arranged in accordance with a categorization system found in Chinese dictionaries of the day.

The second machine was invented by the Presbyterian missionary Devello Sheffield, whose machine also contained roughly five thousand characters. One of the only differences, and a minor one at that, was that Sheffield’s machine was based on a circular rather than rectangular configuration.

Despite the essential similarity of these two early designs, journalists reserved praise for the Westerner’s machine and scorn for that of his Chinese counterpart. Sheffield’s device was hailed as “remarkable,” “ingenious,” and the “most complicated and wonderful typewriter in the world,” while the machine in California was viciously lampooned by the San Francisco Examiner in a racist cartoon portraying the inventor as an ape-like “Chinaman” shouting incomprehensible jibberish to a group of similarly animalistic operators. As one observer complained, the “smashing and banging of the machine and the fierce shouts of the working force suggest a riot in a boiler factory.”

Just over a decade later, a patent for a new model of Chinese typewriter was awarded to Qi Xuan, a young engineering student at New York University. A native of South China, Qi had spent years developing an easier-to-use arrangement of Chinese characters, one that enabled typists to locate words at a much faster rate.

This innovation mattered little to American journalists, however, who instead reveled in recounting the humorous story of the very first letter inscribed on Qi’s apparatus. Authored by the Chinese Consul-General of New York for the Chinese Minister in Washington, the message took two hours to complete despite a length of only one hundred words. Discounted was the fact that the operator had never used the machine before in his life, that he had not received training in Qi’s system of arranging characters, and that he was no doubt interacting with both the inventor and journalists during the process.

The same condescending tone pervaded media accounts in the years following, as in a Washington Post article published two years later about a newly patented machine which surpassed that of Qi. Entitled “The Newest Inventions,” the article placed the new model of Chinese typewriter alongside such absurdities as a “dancing radiator doll” and “a mouse trap for burglars.”

Two decades and nearly one dozen patents later, inventors in the forties and fifties began to develop Chinese typewriters of unprecedented sophistication. Two inventors in particular, Gao Zhongqin and Lin Yutang, created designs that caught the attention of IBM and Merganthaler.

IBM teamed up with Gao to create an electric model capable of producing roughly six thousand characters using only forty-three keys (fewer than most Macintosh laptops). Mergantheler joined forces with Lin, who was already something of a celebrity in America owing to his two New York Times bestselling novels. Like Gao’s machine, Lin’s “Mingkwai” model was also based on a pioneering system of categorizing characters which enabled users to type upwards of ninety thousand different characters using only seventy-two keys.

Despite the unprecedented achievements of both machines, however, neither was able to dislodge the longstanding stereotype. IBM failed to find a market for its prototype or to overcome the widespread assumption that Chinese typewriters were, regardless of their sophistication, curiosities at best and absurdities at worst. Lin’s machine fared somewhat better, praised by some as a device that would “revolutionize Chinese office work.”

To the reporters at the Chicago Daily Tribune, however, news of Lin’s invention was received with an emotion “transcending dismay and yet appreciably milder than despair.” By tangling himself in this silly business of Chinese typewriter (which the reporter assumed must have been “the size of a pipe organ”) the reputation of “our favorite Oriental author” had been sullied. Responses such as these undoubtedly contributed to the difficulties Lin faced in finding a market for his machine. Unable to recoup his research and development expenses, Lin ultimately fell into bankrtuptcy and was pursued by the IRS well into the 1950s.

Over the subsequent two decades, inventors in the People’s Republic of China, Taiwan, Europe, and the United States went on to develop ever more sophisticated and commercially popular models of Chinese typewriters. By the 1970s, their designs had become so advanced, in fact, that the line began to blur between electric Chinese typewriters and early Chinese computers.

On the mainland, engineers developed a pen-based machine that increased speeds by means of an early form of predictive text, anticipating the now widely popular technology by more than two decades. Another engineer, Yeh Chen-hui, used what he had learned from designing a Chinese typewriter to develop a machine that revolutionized the newspaper industry in Taiwan, leading to the complete abandonment of manual typesetting in a number of major publishing houses. To this day, Yeh maintains that his machine was the first true word processor.

Despite this long history of technological achievement equal to, if not more impressive than its Roman alphabet counterpart, the Chinese typewriter has remained an icon of backwardness in the West. When it is not openly ridiculed, at most the machine has served as a medium through which artists have explored the comical, the strange, and the ironic, as in the short-lived mystery series “The Chinese Typewriter” starring eighties hearththrob Tom Selleck, the similarly titled film by experimental artist Daniel Barnett, and the carnivalesque ditty “Her Chinese Typewriter” by indie rocker Matthew Friedberger.

Even The Simpsons entered the fray in 2001. Having been hired to write fortune cookies, Homer Simpson is shown dictating pithy jewels of wisdom to his daughter, who is taking dictation on a Chinese typewriter. “You will invent a humorous toilet lid”; “You will find true love on Flag Day”; “Your store is being robbed, Apu.” He pauses for a moment to confirm that she is keeping up. “Are you getting all this, Lisa?” The frame switches to Lisa, who is postured nervously in front of the absurdly complex machine, pressing buttons slowly and with hesitation. In elongated, uncertain syllables she responds: “I don’t knowwwwww.”

daughter, who is taking dictation on a Chinese typewriter. “You will invent a humorous toilet lid”; “You will find true love on Flag Day”; “Your store is being robbed, Apu.” He pauses for a moment to confirm that she is keeping up. “Are you getting all this, Lisa?” The frame switches to Lisa, who is postured nervously in front of the absurdly complex machine, pressing buttons slowly and with hesitation. In elongated, uncertain syllables she responds: “I don’t knowwwwww.”

It appears that, faced with a rapidly changing China, our views have remained trapped in a past that never actually existed.