Can Biden Beat Van Buren's Curse?

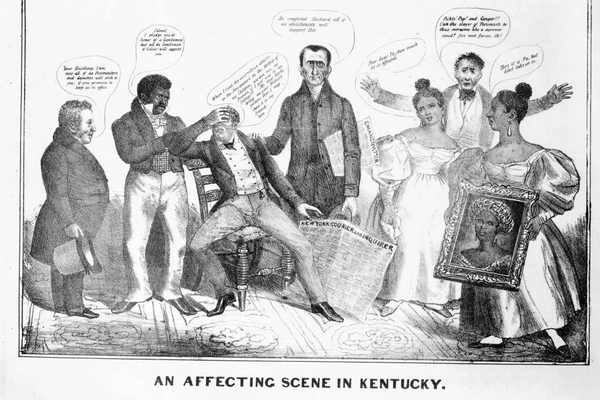

A political cartoon, likely 1836, mocks the personal life of Richard Mentor Johnson and suggests his selection will appeal to

abolitionists and Black people, groups loathed by large parts of the Democratic polity. Image Library of Congress.

Will Joe Biden be different?

As Election Day approaches, he confronts not only an incumbent Republican president flush with campaign cash but also a nearly two-century-old hazard of history. Since the 1830s, the vice presidency has become a dead end for Democratic aspirants to the White House.

Believers in dark wizardry might consider this prolonged string of ill luck as the curse of Martin Van Buren.

Of course, Harry Truman (in 1948) and Lyndon Johnson (in 1964) won presidential campaigns after occupying the nation’s second office. Each, though, ran as incumbent chief executives, following Franklin Roosevelt’s death in 1945 and John Kennedy’s assassination in 1963. Neither was still viewed in the secondary role by the time of their elections.

Over the past 52 years, a trio of three Democrats who were a heartbeat away have sought the presidency. All three—Hubert Humphrey in 1968, Walter Mondale in 1984 and Al Gore in 2000—lost. During that same period, two Republicans who served as two-term veeps—Richard Nixon and George H. W. Bush—triumphed in their pursuit of the Oval Office.

What is it about Democrats?

Except for the atypical cases of Truman and LBJ, not a single Democrat since Andrew Jackson picked Van Buren as his running mate in 1832 has moved up electorally after being—in Mondale’s sobering phrase—“standby equipment.”

Even Van Buren’s political career took a tumble not long after he succeeded “Old Hickory” by winning the 1836 election. The Economic Panic of 1837—with high unemployment, unstable currency and debt defaults—caused the most destructive depression in the young nation’s history, jolting confidence in Washington.

With the economy still struggling and other domestic problems, Van Buren, a diminutive New Yorker with the nickname the “Little Magician,” couldn’t conjure enough electoral tricks to win a second term in 1840. He lost soundly to Whig candidate William Henry Harrison, who appealed to voters by using the ballyhoo of America’s first catchy campaign slogan: “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too.”

Part of the Democratic Party’s predicament that year came from the reputation of Van Buren’s vice president, Richard Mentor Johnson, whom Van Buren never wanted in his administration, let alone in close proximity to presidential power.

The Van Buren jinx starts with Johnson, so he deserves more than cursory consideration.

Having spent 30 years in Congress representing Kentucky—one decade in the Senate and two more in the House of Representatives—Johnson was a conspicuous fixture in Washington.

At one point he sent the capital’s heads shaking for leading a drive to support a government-funded expedition to the center of the earth. As planned, this bizarre scheme involved about a hundred men—transported by reindeer and sleigh—and they were intent on discovering an opening at the Arctic Circle for a descent to the earth’s core.

“As outlandish as this proposal seems, what is truly remarkable is that twenty-three senators joined Johnson in supporting it!” write Mitch McConnell and Roy Brownell II in The U.S. Senate and the Commonwealth: Kentucky Lawmakers and the Evolution of Legislative Leadership (2019). McConnell, the Senate majority leader, and his co-author devote a dozen memorable pages to the country’s ninth vice president.

During the War of 1812, he took a break from House duties to command a regiment of volunteers from his home state that helped win the Battle of Thames in Canada.

This Kentucky colonel returned to the hurly-burly of politics as a combat hero, becoming a favorite of the lionized military leader of the War of 1812: Gen. Andrew Jackson.

Jackson selected Van Buren to run with him for his second-term in 1832 after clashing with his first vice president, John C. Calhoun. Four years later, “Old Hickory” still wielded political clout and vigorously supported Johnson over presidential candidate Van Buren’s choice for a running mate. Jackson won.

Johnson swiftly became a controversial national figure. His common-law wife, Julia Chinn, happened to be a mixed-race enslaved woman (described as an “octoroon” in the racial taxonomy of the day), whom he inherited from his father. Other relationships with enslaved women after Chinn’s death in 1833 kept tongues wagging in Kentucky, Washington and elsewhere.

Commingling personal affairs and government business was never an ethical dilemma for Johnson, who also seemed to care little about his public image. In her widely read and quoted 1837 survey, Society in America, British author Harriet Martineau offered this close-up of Johnson at a Washington dinner: “If he should become president, he will be as strange-looking a potentate as ever ruled. His countenance is wild, though with much cleverness in it; his hair wanders all abroad, and he wears no cravat.”

Johnson’s personal life, duly noted and derided in the press, helped keep him from securing the necessary Electoral College votes for vice president after the 1836 popular vote. For the first and only time in history, the Senate formally assembled to pick the occupant of the nation’s second office. With each senator casting a vote, Johnson defeated Francis Granger of New York, 33 to 16.

Given that Van Buren didn’t want Johnson on the Democratic ticket, the chief conductor of the executive branch had virtually nothing to do with his second fiddle. The official Senate website summarizes Johnson’s service as vice president and president of the Senate in two matter-of-fact sentences: “During his four years in office, Johnson broke 14 tie votes. When not presiding over the Senate, Johnson could regularly be found in Kentucky, operating his tavern.”

Serious questions about Johnson triggered robust debate at the 1840 Democratic convention. This time Jackson dropped his backing, but Van Buren fretted that dumping Johnson from the ticket might bolster the chances of bona fide war hero: “Tippecanoe” Harrison. What to do?

Convention delegates dodged a formal selection, fearing any choice could be divisive. Nobody was nominated for the second place on the ticket, and 1840 became the only time since the passage of the 12th Amendment (spelling out the process to choose the president and vice president) when a major party failed to slate two people on a national ticket.

Van Buren ran alone. He lost alone.

Historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. thought the 12th Amendment, ratified in 1804, turned the vice presidency of the 19th century into “a resting place for mediocrities.” He’s accurate, but they proved to be quite ambitious mediocrities.

Johnson, who campaigned unsuccessfully on his own to remain as vice president in 1840, sought the Democratic presidential nomination four years later—and got nowhere.

James Polk won in 1844, and his promise to serve just one term made his vice president, George M. Dallas of Pennsylvania, drool for the 1848 Democratic nomination. At that year’s convention he could convince only three delegates he was White House timber.

Dallas followed Johnson in what’s turned into a Democratic Party tradition of defeat for hapless, if not cursed, White House hopefuls. Adlai Stevenson I (Grover Cleveland’s second VP), Thomas Marshall (Woodrow Wilson’s two-term second banana), John Nance Garner (Franklin Roosevelt’s first Number Two) and Alben Barkley (Truman’s vice president) all thought they could find success at Democratic conventions by using their performances in front of delegates to vault to the highest office.

None, however, mustered much support. Garner, remembered for his bon mot that the “vice presidency is not worth a bucket of warm piss,” even ran unsuccessfully against FDR—his boss—at the 1940 convention.

Henry Wallace, FDR’s second vice president, was dropped from the 1944 ticket and replaced by Truman. Wallace’s consolation prize, appointment as Secretary of Commerce, continued for a year-and-a-half until Wallace and Truman parted ways in 1946 over the president’s confrontational approach to the Soviet Union. After his firing as Secretary of Commerce, Wallace sought revenge. He mounted a presidential campaign against Truman in 1948 as the Progressive Party candidate.

Wallace’s untraditional and ill-fated attempt at political advancement resembled a similar effort by John Breckinridge, James Buchanan’s vice president during the much-reviled Democratic administration between 1857 and 1861.

Stephen A. Douglas, a senator from Illinois, won the 1860 Democratic nod for president, but disgruntled Southern Democrats, largely pro-slavery stalwarts, bolted, conducting a separate convention that chose Breckenridge from Kentucky as the nominee.

Though Breckinridge received just 18 percent of the popular vote (to Republican Abraham Lincoln’s 40 percent and Douglas’s 29 percent), Southern states awarded Breckinridge 72 electoral votes to Lincoln’s 180. Douglas got just 12.

Starting with Van Buren, there have been 17 vice presidents in Democratic administrations. Three made it to the White House—Van Buren, Truman and Lyndon (not Richard) Johnson. Eleven tried and failed either to win the highest office or the party’s nomination. (Two—William R. King, Franklin Pierce’s VP for just six weeks, and Thomas Hendricks, a nine-month Number Two in Cleveland’s first term—died in office.)

Joe Biden is Number 17, and he faces another hurdle of history. Except for Thomas Jefferson in the controversial election of 1800, no candidate of either party who’s been vice president has defeated an incumbent president to grab the brightest brass ring of U.S. politics.

Will the curse of Martin Van Buren continue to cast its sinister spell on Democrats in 2020, or is this the year when history takes a dramatic turn by elevating an understudy to become the leading character on America’s—and the world’s—stage?

Place your bets.