The Schlesinger Diaries—A Gift to Historians that Keeps Giving

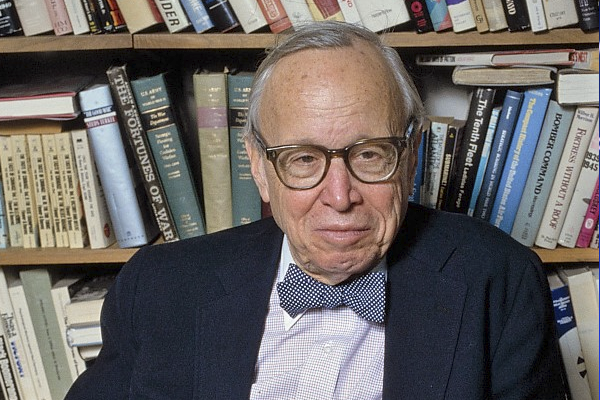

Fourteen years after the passing of Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., his diaries continue to provide historians with important new information. The latest beneficiary is John A. Farrell, whose biography of Ted Kennedy contains disturbing new details concerning the Chappaquiddick cover-up, which Farrell obtained by gaining access to unpublished sections of Schlesinger’s diaries.

My own experiences with Schlesinger and his diaries concerned a different American political leader, President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The information that emerged was deeply troubling, to say the least.

“We Have No Jewish Blood”

My first encounter with Schlesinger was related to a meeting that President Roosevelt held on August 4, 1939, with a political ally, Sen. Burton Wheeler (D-Montana). They discussed possible Democratic candidates for president and vice president in the event FDR did not seek re-election in 1940; Wheeler composed a memo for his private files recounting their conversation.

According to the memo, FDR dismissed the idea of vice president Jack Garner as the party’s presidential nominee on the grounds that he was too conservative: “[Roosevelt] said ‘I do not want to see a reactionary democrat nominated.’ The President said, ‘I love Jack Garner personally. He is a lovable man,’ but he said, ‘he could not get the n—- vote, and he could not get the labor vote’.” (Wheeler did not use the dashes.)

The president also expressed doubt about the viability of a ticket composed of Secretary of State Cordell Hull for president and Democratic National Committee chairman Jim Farley for vice president. Sen. Wheeler wrote:

I said to the President someone told me that Mrs. Hull was a Jewess, and I said that the Jewish-Catholic issue would be raised [if Hull was nominated for president, and Farley, a Catholic, was his running mate]. He [FDR] said, “Mrs. Hull is about one quarter Jewish.” He said, “You and I, Burt, are old English and Dutch stock. We know who our ancestors are. We know there is no Jewish blood in our veins, but a lot of these people do not know whether there is Jewish blood in their veins or not.”

The memo is located in Wheeler’s papers at Montana State University. The file also contains two letters sent to Wheeler from Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. in 1959. At the time, Schlesinger was working on The Politics of Upheaval, the final installment of his three-volume history of the New Deal. According to the letters, Sen. Wheeler sent Schlesinger a copy of his 1939 memorandum on the “Jewish blood” conversation with FDR. Schlesinger, after reviewing the memo, wrote to Wheeler that the document “offer[s] valuable sidelights on history.”

Nevertheless, Schlesinger never quoted FDR’s remarks about “Jewish blood” in any of the many books and articles he subsequently wrote about Roosevelt and his era. Ironically, in one of those articles (published in Newsweek in 1994), Schlesinger specifically defended FDR against any suspicion that he was unsympathetic to Jews; he approvingly quoted Trude Lash, a friend of the Roosevelts, as saying, “FDR did not have an anti-Semitic bone in his body.”

I wrote to Schlesinger, in 2005, to ask why he had withheld Roosevelt’s “Jewish blood” statement from public view. Schlesinger insisted he had done nothing wrong, since, in his view, Roosevelt’s remark was not antisemitic. “FDR’s allusion to ‘Jewish blood' does not seem to me incompatible with Trude Lash’s statement,” Schlesinger wrote me. “It appears to me a neutral comment about people of mixed ancestry.”

But if that were the case--if Roosevelt’s remark about Jewish blood was indeed “neutral” and not an expression of bigotry--then why did Schlesinger decide to suppress it? Why didn’t Schlesinger mention it in one of his published writings about FDR? After all, it certainly sheds interesting light on Roosevelt’s thought process in considering whether to run for a third term in 1940. Why didn’t Schlesinger at least acknowledge FDR’s statement when he himself raised the antisemitism issue in his Newsweek essay, and let readers judge for themselves?[1]

Bombing Auschwitz

My second Schlesinger experience involved his diaries. This episode concerned an exhibit at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, in Washington, regarding the refusal of the Roosevelt administration to bomb the railways and bridges leading to Auschwitz, or the gas chambers and crematoria in the camp itself.

When the museum opened, in 1993, the text accompanying that exhibit stated, accurately, that “American Jewish organizations repeatedly asked the U.S. War Department to bomb Auschwitz.” Historians have documented calls by thirty officials of Jewish organizations or publications for such bombings, as well as one instance in which a Jewish official supported bombing the railways but urged using ground troops instead of air strikes on the gas chambers for fear of hitting prisoners by accident.

Three years later, however, the museum quietly changed the text of that panel to: “A few Jewish leaders called for the bombing of the Auschwitz gas chambers; others opposed it….No one was certain of the results…” The museum never provided evidence from historians to support making that change. In fact, the change would never even have come to light if a reporter for a Jewish newspaper not caught wind of it.

An accurate text in the museum had been changed to an inaccurate one. Not only was the new wording inaccurate, it carried a significant broader implication—if only “a few” Jewish leaders favored bombing, while “others” (which sounds like a comparable number) opposed it; and if nobody could be “certain” of the results; then nobody today can reasonably criticize the Roosevelt administration for not bombing the death camp. In short, changing the panel got FDR off the hook.

It is important to emphasize that the positions taken by Jewish leaders concerning bombing Auschwitz had no actual impact on U.S. policy. The Roosevelt administration decided in February 1944—four months before the first Jewish request for bombing— that it would not use military resources “for rescuing victims of enemy oppression.” That U.S. policy decision never wavered. But that fact has not stopped some contemporary defenders of FDR from citing alleged Jewish opposition to bombing in order to exonerate the Roosevelt administration.

That said, a glaring question presents itself: why did the museum change its exhibit? The answer would emerge, years later, from Arthur Schlesinger’s diaries.

“A Successful Campaign”

During the three years between the opening of the U.S. Holocaust museum and the revision of the bombing panel text—between 1993 and 1996—something curious happened. A retired nuclear engineer in Seattle, named Richard H. Levy, suddenly took an interest in the bombing issue. Although he had no professional training as a historian and no publications on the topic, Levy wrote a lengthy memorandum in which he argued that it was “beyond the power” of the Allies to interrupt the Holocaust by bombing Auschwitz or the railway lines leading to it; that many prominent Jewish leaders opposed such bombing; and that the museum should change its exhibit on the bombing issue to reflect these assertions. Those positions contradicted the findings of every serious historian who had researched the subject. Yet Levy and his arguments were championed in a series of articles and speeches by William vanden Heuvel, then president of the Roosevelt Institute. The institute’s mission is "to carry forward the legacy and values of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt.”

Remarkably, Levy was invited to speak at the U.S. Holocaust Museum; his bombing memorandum was published in a book of proceedings from a conference that he did not attend, and the memo was then reprinted, in 1996, in the museum’s journal, Holocaust and Genocide Studies—despite the journal’s own policy of considering only submissions that have “not been published and will not be simultaneously submitted or published elsewhere.”

There was more: in a 1997 newspaper article, vanden Heuvel wrote that Levy “met with representatives of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum” and persuaded them to change the bombing exhibit. Vanden Heuvel did not indicate that he had played any role in the process.[2]

His account raised more questions than it answered. How, without any outside influence, could a memo about Auschwitz by a retired nuclear engineer—a memo that was at odds with the findings of the experts in that field—convince a major museum to change an exhibit?

The answer came from Schlesinger’s diaries, large portions of which were published posthumously in 2007 by Penguin Press. Schlesinger was a close friend of vanden Heuvel and had collaborated with him in efforts to publicly defend FDR’s Holocaust record. In a diary entry dated August 21, 1996 (p.789), Schlesinger celebrated the conclusion of what he described as “Bill [vanden Heuvel]’s successful campaign to persuade the Holocaust Museum to revise a most tendentious account of the failure to bomb Auschwitz.”

So there HAD been a “campaign” (behind the scenes) by the president of the Roosevelt Institute to change the bombing exhibit. Evidently, the change was not—as vanden Heuvel had claimed—the result of Levy’s persuasive powers; nor was it the result of the museum’s historians discovering errors in the exhibit. The original exhibit, in fact, was accurate; it was changed--according to Schlesinger--because of the Roosevelt Institute’s “campaign.” Precisely what type of pressure vanden Heuvel’s campaign employed was not specified in Schlesinger’s diary. But the outcome of the campaign certainly indicated that the pressure had worked.

Obviously, history museums update their exhibits from time to time. If a reputable historian points out an inaccuracy, a correction is made. Or if the museum staff itself uncovers new information, an exhibit will be revised. But it is another matter entirely to change an accurate text to an inaccurate one, in response to pressure from the president of an institute that has an agenda--in this case, the agenda of protecting the “legacy” and image of its namesake, Franklin D. Roosevelt.

“There Was Pressure”

Schlesinger’s posthumous revelation went unnoticed by the news media and the academic community for more than two years. Finally, in 2009, New York Times reporter Patricia Cohen raised it. In the course of preparing an article about the bombing issue, Cohen interviewed Dr. Michael Berenbaum, who had been research director of the U.S. Holocaust Museum at the time the exhibit was changed. Cohen asked Berenbaum whether vanden Heuvel indeed had pressured the Museum to make the change, as Schlesinger’s diary entry indicated. Berenbaum replied (as quoted on Cohen’s blog on October 5, 2009): “There was pressure from the Roosevelt Foundation and we paid no attention whatsoever to that pressure.”

Berenbaum’s acknowledgement that “there was pressure” was significant. It contradicted the narrative that vanden Heuvel had presented in his lectures and articles; according to vanden Heuvel Levy had, on his own, managed to persuade the Museum to make the change.

As for Dr. Berenbaum’s statement that he and his colleagues “paid no attention” to the pressure--one can only note that they made the very change the Roosevelt Institute pressed them to make, despite the fact that the proposed change had no basis in the historical record.

An Error Remains Uncorrected

In the autumn of 2009, my colleagues and I provided the U.S. Holocaust Museum with new research identifying the 30 Jewish officials who advocated bombing Auschwitz or the railways. We also asked that the original caption in the bombing exhibit be restored.

More than two years later, in early 2012, the Holocaust Museum leadership responded with a ten-page memorandum in which they agreed that at least 26 Jewish officials had supported bombing.

That directly contradicted the statement in the museum’s exhibit that only “a few” Jewish leaders called for bombing. Twenty-six is not “a few.”

Nonetheless, today, thirteen years later, the inaccurate caption is still on display at the museum.[3] The erroneously-described position of the Jewish leaders continues to be used to, in effect, exonerate the Roosevelt administration on the issue of bombing Auschwitz. Presumably Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. would be pleased. But it does a disservice to the historical record.

[1] “Confidential - Memo on conference at the White House with the President---August 4, 1939,” Burton K. Wheeler Papers, Box 11: File 18, Montana State University, Bozeman, MT; Schlesinger to Wheeler, November 30, 1959 and December 22, 1959, Wheeler Papers, Box 11: File 18; Arthur Schlesinger Jr., “Did FDR Betray the Jews?,” Newsweek, April 18, 1994, p.14; Schlesinger to Medoff, September 4, 2005.

[2] “FDR Did Not Abandon European Jewry,” Washington Jewish Week, February 27, 1997.

[3] Wyman and Medoff to Luckert, September 21, 2009; Luckert to Wyman and Medoff, January 10, 2012.