The non-atrocity of Getafe

While in Wales recently I chanced upon a copy of Robert Stradling's Your Children Will Be Next: Bombing and Propaganda in the Spanish Civil War 1936-1939 (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2008). My description at the time was that this book 'Argues that the memory of Guernica has obscured earlier atrocities, especially the 1936 bombing of Getafe near Madrid'. Now that I've read Your Children Will Be Next, it's clear that I seriously misrepresented Stradling's argument in one crucial respect: he doesn't believe the Getafe atrocity ever actually happened, or at least if it did, there's no good evidence for it now. And that, nevertheless, this non-event had important consequences for the propaganda battle in Spain, for the subsequent memory of the Spanish Republic, and for our own reactions to the use of airpower against civilian targets. It's such an interesting and important book that it's worth correcting my mistake, and digging bit deeper into Stradling's thesis.

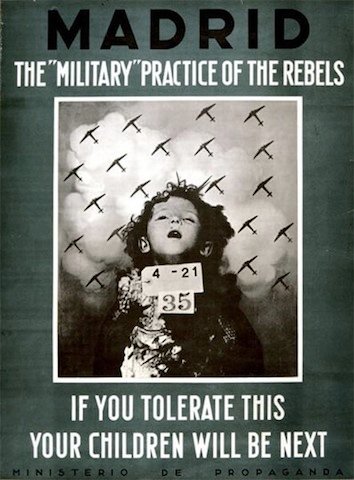

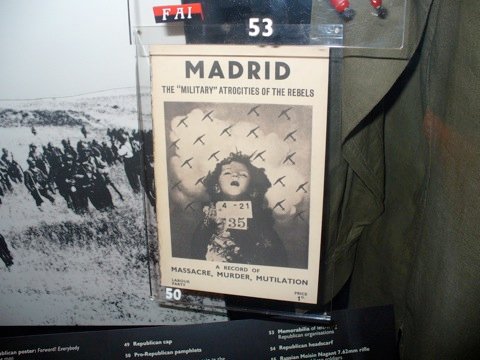

Firstly, what was supposed to have happened at Getafe? I must admit to not having heard of the incident before. It was claimed (mainly in the foreign left-wing press) that on 30 October 1936, Nationalist (meaning German) bombers deliberately bombed civilians in Getafe, a small town near Madrid, flying low to mark their victims and killing dozens of children. Photographs of their bodies, with identification labels on their chests, were used in several Republican propaganda productions, the best-known of which is shown above: 'If you tolerate this, your children will be next', a combined appeal to humanity and self-interest. Stradling traces the propagation and influence of The Poster, as he calls it: it was used by both the Communists and the Labour Party in Britain for their pamphlets (below is the Imperial War Museum's copy of the latter's). It helped turn opinion in the democracies against the Nationalists in this crucial early part of the war, when a swift victory by Franco had seemed assured. Memoirs and poems from the period attest to the power of its imagery.

But Stradling searches for evidence of this attack on Getafe in Spanish newspapers and potential eyewitness accounts by Spaniards and foreigners, and really can't find any, beyond some dubious memoirs published later. Nor are there any municipal records of the bombing, though the town's capture by Nationalist forces a few days later could explain this. Stradling argues that the story of Getafe was concocted by Communist propagandists in Madrid. Getafe may or may not have been bombed on the date in question -- it was the site of an important Republican military airfield -- but deliberate targeting of civilians is unlikely, in his opinion (239). And the dead children in the photographs didn't live in Getafe at all, but in Madrid, so if they were killed by bombs anywhere it was there. (The name of the girl in The Poster is María Santiago.) This does puzzle me though: Stradling doesn't tell us why bombing in Getafe was deemed as better propaganda than Madrid, and indeed the images soon became detached from Getafe specifically and stood for Nationalist atrocities against women and children generally, as even The Poster above shows: it nowhere mentions Getafe, only Madrid. Getafe had meaning only for a few short months in late 1936.

One of the virtues of this book is the attention Stradling pays to the bombing of cities by both sides in the war, despite the perception -- then and now -- that this was something only the Nationalists did. The Republic characterised its own attacks on Nationalist-held cities as having military objectives or being reprisals. They were little noticed outside Spain at the time, and are virtually forgotten now. Instead the Nationalist air raids on cities and towns came to stand for fascist barbarism and for the war itself: Guernica above all, of course -- and then Guernica came to stand for Guernica, something I've remarked upon before. (Stradling uses the Basque name for the city, Gernika, to distinguish it from Picasso's painting.) These won the propaganda war for the Republic, in Stradling's view, but it was Getafe which created the narrative which accounts of these later air raids conformed to: the raids were militarily unjustified attempts at creating terror among civilians, and killed disproportionate numbers of women and children. Stradling suggests that this also set the pattern for propaganda treatment of air raids from the Second World War to Lebanon (xi, xii-xiv), though he exaggerates here: the same pattern was evident in the First World War, and it was part and parcel of the moral case against the knock-out blow theory. Still, although it's by no means a complete history Your Children Will be Next is certainly the best account of the air war against Spanish civilians I've come across.

Stradling writes also about the connections between Wales and the war in Spain. I can't judge whether these are as strong as he claims (though the fact that a Welsh band released a hit song in 1998 called "If You Tolerate This Your Children Will Be Next" is suggestive). But his suggestion that the both the burning, in September 1936, of a RAF bombing school by Welsh nationalists and the reaction to it was intensified by the outrage over the contemporary bombings in Spain (18-21) is an interesting one. But a greater appreciation of the civil defence context would help here: that Welsh government officials were undertaking training in preparation for air raids (181) surely has more to do with the British government ARP programme which began in 1935 than any solidarity with Spanish civilians.

Stradling constantly and ostentatiously qualifies his conclusions. This is because of the hold the memory of the Spanish Republic still has over many people today: any approach towards moral equivalence between it and the Nationalists is seen as almost on a par with being pro-Hitler, or at least pro-Mussolini. And, ironically, this is partly a legacy of the very propaganda exercises Stradling explores so thoroughly. The Poster and its like did their work well.

Image source.