The Oceans Curated: A Review of 'Shipwrecked' at the Singapore ArtScience Museum

Cross-posted at AHC.

I was back in Singapore a little while ago, and took the opportunity to revisit an old obsession of mine. Some of you may recall that two years ago, I previewed a marvellous collection of Tang treasure from a shipwreck found near Belitung, an island off the coast of Indonesia. I was fascinated then by how a find like this gets shaped into history, and thought that curators of this material would likely try to find a way to, as I wrote, “inscribe Singapore into a wider and more ancient world history, and to give historical credence to a position that is crucial to Singapore’s self-image today: as a global maritime entrepot, and the lodestone on which Southeast Asia turns”. That has come pretty much into total fruition at the Singapore ArtScience Museum’s new exhibition, entitled Shipwrecked: Tang Treasures and Monsoon Winds. It’s even made it to the Lonely Planet.

The exhibition is curated jointly by Singapore’s Asian Civilizations Museum and the Smithsonian Museums of Asian Art in Washington DC. Together, they’ve done a magnificent job of restoring and presenting their material. All the artefacts have been restored to all possible brilliance, except for the few which have been left in their original coral-encrusted form. The first gallery is cast in shadowy, warm wooden hues, redolent of the hull of a ship. We then move gradually into colder underwater colours—deep blues, turquoises, aquamarine. The exhibition saves the true treasures for the last few rooms—the solid gold, silver and green-splashed porcelain wares, submerged in near pitch blackness and illuminated as though by search spotlights. They have become beautiful, mysterious icons of the Belitung wreck. One emerges from the exhibition, blinking owlishly, into the bright lights of the inevitable souvenir shop.

Two themes dominate the exhibition, and are emphasized in the above clip—one of the first things you’ll watch when you enter the gallery. (NB: the above clip has no corresponding audio track; see video details).

First and foremost, the Belitung wreck testifies to an extraordinarily early age of global trade. Networks of material, cultural and intellectual exchange linked the two great empires which dominated the ninth century world: Abbasid Iraq and Tang China. This was an export-driven trade. Commissioned designs adorn some 55,000 mass-produced plates which formed the bulk of the Belitung wreck’s cargo, while the presence of gold and silver wares on board suggest elite and private collection, or high-level diplomatic tribute.

A second theme is the exhibition’s strong focus on the imperial capitals, Baghdad and Chang’an, as keystones of this vast inter-Asian trade. Over the eighth and ninth centuries, cross-continental travel became more difficult and relatively less efficient. Camels could never carry as much as ships, and political turmoil both in the West and East, including the Arab Conquest and civil war in Tang China, made the Silk Road dangerous for merchants. Land routes, which sprawled across the vast Asian continent and linked Baghdad and Chang’an, gave way to sea routes, and privileged port cities such as Yangzhou and Guangzhou in an economy becoming global on new, maritime terms.

The presence of this single dhow at Belitung thus furnishes evidence of a tremendous inter-empire maritime trade, demonstrates the early dominance of China as a powerhouse of industrial production, and confirms a long-held belief that Persian and Arab vessels carried the China trade. As an archaeological find, it has been transformative, and will—if you’ll forgive the pun—make waves for years to come.

“Deep” questions

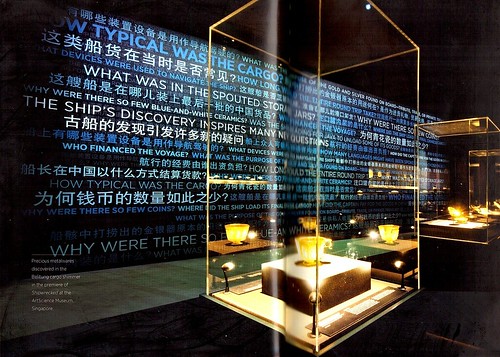

Photo scanned from exhibition catalogue, property of Visual Media, Marina Bay Sands

The exhibition ends with a wall-sized collage of questions, designed to emphasize the supposedly “deep” questions which the shipwreck “inspires”. The questions are presented as though they are, or ought to be, of equal interest, and with such self-conscious gravitas that the end effect is somewhat silly. Some are genuinely interesting, though not especially profound. Why were there so few blue-and-white ceramics? An exciting question with a large amount of research already behind it: even Wikipedia knows a bit. How typical was the cargo? A solid general question to be answered by solid research. Others are prosaic factual questions, the answers to which would shed welcome light on the details of ninth century maritime trade: How did the captain pay for goods in China? Who financed the voyage? How long did the entire round trip take? What devices were used to navigate the ship?

A few are somewhat more banal. Was the ship heading for Java to unload some of its goods? Um, probably? What was in the sprouted storage jars? Perhaps, more stored ceramics? The oddest question was this one: How many languages might have been spoken among those on board? This rather loaded question echoes what was, to me, the most incongruous part of the exhibition: the section entitled "A Multicultural Crew". It explored the cultural diversity of the crew members through their personal effects, and spent a good deal too much time driving home the rather unastonishing fact that there were probably people of different racial origin on board the ship.

Deeper questions

But one question nagged at me throughout the exhibition, and was no less interesting for its omission from the wall. The question is this: What does Singapore really have to do with the Belitung wreck at all?

We are told throughout the exhibition that the dhow sunk “400 miles south of Singapore”, rather than, say, a few miles off the coast of Indonesia. We are told frequently that Singapore inherited the “strategic position” which the great Indonesian empires of Srivijaya and Sailendra used to hold—just as they were the central powers of the region then, so too is Singapore today. That is why, we are then to think, it makes sense for Singapore to both host as well as feature in this exhibition.

But the place now known as Singapore existed only tenuously, if at all at the time. It was called “Temasek”, which is an Old Javanese name meaning “Sea Village” or “Sea Town”; it was controlled by the Srivijayan Empire and supposedly only founded by a Srivijayan prince around the twelfth or thirteenth century. Ancient Sumatran and Javanese histories are not explored to any depth in the exhibition, despite being central to the story of the Belitung wreck, and particularly given the two themes—imperial capitals and global trade—which the exhibition’s curators have chosen to foreground. Having Singapore appear in this map of the ninth century world feels as anomalous and anachronistic as regarding Beijing as the capital of Tang China. The closer truth is that between Baghdad of Abbasid Iraq and Chang’an of Tang China lay not Singapore, but Palembang of Srivijayan Indonesia. What does "Singapore" have to do with any of this? The conceptual stretch comes out clearly in the video above, at around [1:18-1:22], and clumsily in this short promotional clip.

It’s not surprising that Indonesia plays such a small part in this story. The Belitung shipwreck has provoked some pretty acrimonious controversies: Indonesian claims on the treasure, disputes about remuneration and so on. One small part of the exhibition touches on these controversies in an attempt to pre-empt difficult but unavoidable questions about the shipwreck’s provenance and discovery. There is a large, wordy panel emphasizing the ethical and technical legality of the treasure’s acquisition, and visitors are politely pointed to this website for further information. But I wonder how many Singaporean visitors bothered to read and follow up on this, when everything about the exhibition is designed to titillate the senses and provoke a bland and unthreatening wonder. Really, this is an exhibition in which the “deepest” questions are helpfully put up on a wall, in order that you can be told how exactly to “open your mind” to the “mysteries” and “wonders” of history, and then wander off to buy some souvenirs. It is a profoundly Singaporean exhibition.

Convenient truths

In many ways, I can understand why it’s better for curators, historians and archeologists that Singapore now possesses the Belitung treasure. Singapore has the expertise, technology and above all the money to ensure these invaluable artefacts are conserved and protected. Indonesia enjoys some notoriety among archaeologists for being a place in which incredibly rare antiques are dug up by amateurs, flogged cheaply to discerning dealers, and dissipated with large profit margins into private collections. Maintaining the integrity of the Belitung collection has offered a rare window into the distant past. In this respect, the Sackler and Freer galleries made a sound pragmatic decision to throw their support behind Singapore’s purchase of this collection. As Julian Raby, the director of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, asserts in his foreword to the exhibition catalogue, Singapore is in the best position to become the “catalyst for developing expertise and resources not only in Singapore itself but across the entire ASEAN region”.

But Singapore’s appropriation of the cargo has enabled it to make important claims about its own past which have, I think, impinged in unsettling ways on the tone and message of the exhibition. The thematic emphasis on global trade and global cities is milked for all nationalist worth. The Belitung wreck, far from illuminating a ninth century world of Srivijayan trade, is harnessed to shore up the story of Singapore, the modern cosmopolis and hub of Southeast Asia. “Truly,” CEO of the Singapore Tourism Board Aw Kah Peng declares in her foreword, “this collection helps tell the story of how Singapore grew from a fishing village into the modern metropolis it is today”, and of how Singapore “benefited from its strategic location in the global trade network”. The oddly “multicultural” angle of the exhibition makes sense principally when we realize that it shores up modern Singaporean “CMIO” propaganda about models of ethnic diversity within its own frontiers. From the multicultural crew of the Belitung wreck, who between them spoke so many languages, as Singapore Minister for Foreign Affairs George Yeo declares sagely, “we can learn lessons that apply today. Diversity may be a reason for conflict, but it also can be a source of learning and creativity. In celebrating that glorious past, we can draw inspiration for the future.”

In this way, the past is yoked to present truth claims—but hey, what could be wrong with that? It gives everyone something to cling on to—doesn't it? It's just a harmless, malleable little piece of history to fly with pride from a national mast, in this world of nations and nationalism—isn't it? As I made my way through the beautiful, shadowy galleries, I found myself walking for a while behind a handsome Filipino exhibition guide accompanying two Singaporean women through the exhibition. When they reached that incongruous “Multicultural Crew” section, he paused to tell them: “You know, there is a theory that the crew was—” and here, he leaned closer, conspiratorially, “a multicultural one!” Enthused nods from the two women spurred him on. He leaned even closer. “There is also a theory that, you know, the crew may even have been…partly Filipino!!” And he stepped backward quickly, opening his hands palms up, as if to say (and he did say, with a smile), “Just my thought, I am not too sure!” The three of them laughed together, and moved on to the next section, the next artefact, the next beautifully-presented claim to national truth.

'Shipwrecked' is on show at Singapore’s ArtScience Museum from 19 February to 31 July. Tickets at S$30. The show is expected to travel to museums around the world over the next five to six years.