The correct target for the humanities survivalist

Recent events in the UK academic sphere, which I wrote about here, have had me wondering once again how we go about mounting any kind of counter-attack to the erosion of the humanities' importance in public policy. Pressure groups exist, opposition is voiced by many (though not, as said, by some of the bodies that ought to represent us) but we lack a concerted voice with which to speak back. This post muses a bit (and the ideas here are still forming and I'd welcome critique) on how far we really need to have a strategy and a fully-formed ideology in order to start the fight back.

It's painful of course to have to justify the study of the humanities, and specifically history, at all. It's the reverse of the grand Louis Armstrong answer to the question, "what is jazz?" He, of course, replied, "If you have to ask the question, you'll never know the answer". Similarly with Our Stuff, writ large: if you have to ask why it's worthwhile, I may not be able to convince you. Only actually meeting the stuff and finding something fantastic will do this. There are plentiful figures that show that plenty of people get this. Books on historical topics, despite their often ridiculous prices, show no signs of dropping off booksellers' stocklists and show a widespread interest in the results of academic research, even if more at second-hand; at first-hand, we see this interest continuing in the recruitment to degree programs, which is still large even if dropping (in the UK at least). But, two things: some people obviously don't see the point, and someone still has to pay for it (which is our Achilles's Heel).

So, if we have to make a case for history, what is it? Well, what are we actually doing? Are we providing a gateway to the fantastic range of human possibilities? Yes, I would say, we are. Are we selling skills and techniques of thought, marketing history as a brain upgrade? Here I am less sure: we speak in these terms but don't really sell it and perhaps we should, not least because then the Otherer the material the better for challenging and opening up the brain. Early-interest types like myself could occupy that space very thoroughly. Or, are we even engaged in a wider, pan-humanities endeavour to better understand how interconnected we are and somehow thus create a more universally caring society where everyone is that bit more excellent to each other? Well, some of us are, but this may be a bit too ambitious for the immediate agenda, which is more one of survival, and in any case this one requires the politicians currently vested in their interests to roll over and acquiesce in their removal, so may be unrealistic.

Okay, then, what are the problems in our way? Poverty, obviously: to do this well needs resources, and they must be invested even though their returns are hard to quantify (not least because, even if there are returns that could be measured in terms other than simply salaries—terms of self-perceived quality of life, mental health problems, later acuity or sociability, for example—these would all need to be measured by researchers from other fields and would operate on a timescale too long to induce politicians to act on them anyway). The great vulnerability in any case we make for our importance is the zero-sum one, that the people can only be asked to pay so much tax and that we must compete within that limit. It's easy to say that Britain should pay for historians not war, and hard to disagree that society would probably benefit more from what we do, however arcane, than from the war in Afghanistan—but it's a lot harder to argue that Britain should maintain historians at the cost of a certain war-readiness that costs an awful lot even before we start campaigning. The case is even harder to make against hospitals, and so on. There may be better places to attack, but to step into the zero-sum trap is death since it lets someone else tell us what budget is reasonable in the first place. Furthermore, we can see by now that we can't make this case by simple argument alone, that has arguably failed.

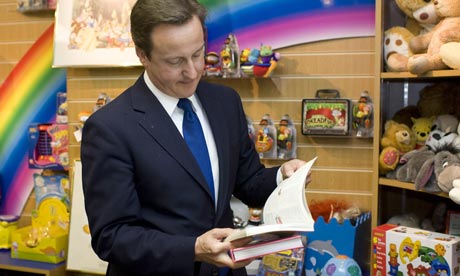

The other problem is anti-intellectualism. In an environment where knowing stuff out of books (or even off the web) can be thought not just unnecessary but effete, we are in trouble. The current ruling class can actually get by on saying they don't have time to read books, and we must then reply, well what do you know then? And we're letting you run things? We need to call out ignorance where there should be informedness, and not confuse that with calling out stupidity.

John R. Fleming is Louis W. Fairchild Professor of English and Comparative Literature emeritus at Princeton University and writes a blog called Gladly Lerne, Gladly Teche, which hits this nail right on the spot with a post about some recent trouble that French President Nicholas Sarkozy has had. (I know, I know, be more specific.) It's very much worth a read in itself but the key element goes:

Some time ago President Sarkozy came upon a copy of the civil service exam devised for aspirants to the qualification of attaché d’administration. He was amazed to find therein a question about this seventeenth-century novel – a question placed there, in his opinion, by "a sadist or an imbecile". How often, he wondered aloud, are you likely to discuss the Princesse de Clèves with the lady at the Post Office counter?

Any literature professor can be indignant at the philistinism of a remark that indicates so thorough an ignorance of or disdain for the ideal of a liberal education. But an American professor may not make it that far, having already succumbed to stupefaction at the evidence of a popularly elected politician who has read the Princesse de Clèves, even if he didn’t like it. The implication that the local postal clerk might have read it is too radical even to entertain.

The reaction to Nicolas Sarkozy’s off-the-cuff literary criticism was not limited to academic departments of literature. There was a national reaction. La Princesse de Clèves is a fine novel, but it’s really subtle. Most of the action is mental. It lacks the in-your-face sex of Les liaisons dangereuses. It was perhaps fading a bit in the French national consciousness. President Sarkozy changed all this. There was an immediate spike in sales. At least two publishers fast-tracked new editions. Round tables of television pundits discussed Madame de la Fayette’s masterpiece. At various places in the land there were public marathon readings. Le Monde opined that among the President’s most conspicuous achievements to date was the "salvation" of La Princesse de Clèves.

This has stuck with me since I read it, because it seems to me that this is what we want. Not, admittedly, the situation in which a politician's opinion of a novel can lose him or her standing, but that where he can be shamed for being insufficiently thoughtful, well-read or generally educated. Running a country, after all, is presumably a complex job: that people can get to do it by professing their ignorance and lack of intellectual preparation should really horrify the electorate. Would we be happy with an airline pilot who told us that he had no pilot's license because the differences between airliners and paper planes were really a conspiracy by flying instructors to keep themselves in work? And so on. But we are ruled by people who reject expert advice when it doesn't suit their policy and who can't handle complex data, so ignore it. There are people employed to do this stuff for them, but it's not getting through. So maybe what we need is to make the ill-educated ruling class ashamed of their lack of smarts. Is what we need is an environment in which people are sorry, even ashamed, they don't know more, and I mean specifically people in power? I argue yes, and a lot is at stake if we can't recreate it. Whatever we're trying to achieve, in fact. And this is maybe the important bit: I don't think we need to agree on that to agree on the counter-attack. Let's go to it: name and shame.