Improbable arguments in ninth-century Girona

While I was working up a recent conference paper I had to spend some quality time with the documents of Carolingian-era Girona for the first time. I've avoided Girona for two reasons: firstly, and most importantly, when I began my Ph. D. it was only just fully in print and those volumes weren't in libraries I could easily access, whereas since 2003 everything from the area between 817 and 1000 has been collected handily in two volumes of the Catalunya Carolíngia.1 From the fact that these two volumes encompass four counties' material, as opposed to the two counties in three thicker volumes I usually work from for Osona and Manresa,2 you'll maybe guess reason two, that there really isn't very much compared to the frontier areas, which also speaks of reason three, I wanted a frontier, and Girona has never been one except for a brief period in its existence, 785 to 801, when it was number one Carolingian base for further campaigns into Spain. The city has arguably never been that important again, which may explain its weird fascination with Charlemagne, a ruler who never went there and none of whose documents it preserves.3

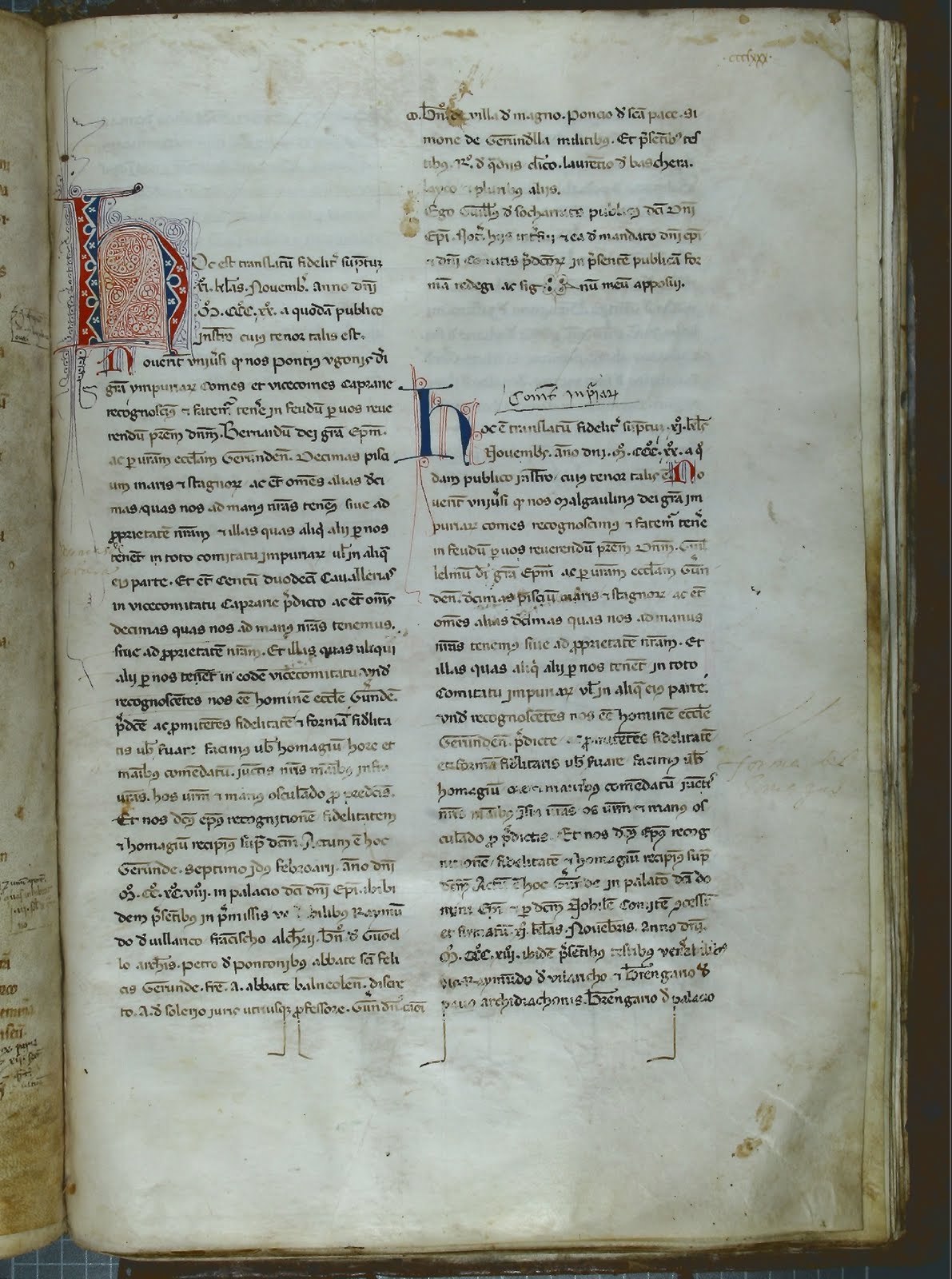

(Storefront of the Llibreria Carlemany, Girona.)

(Storefront of the Llibreria Carlemany, Girona.)

There is also the factor that what I do has become increasingly focussed on having original documents. This is partly because it's much easier to tell whether they've been messed about with subsequently (or indeed not—sometimes they're just weird, and you can't tell in a copy which was true), but it's also because copying tends to be selective and so you only get certain things. Now, at Urgell, at Vic, and at a few places outside Spain, St Gallen for example, the fact that there was a cartulary later compiled doesn't mean that the relevant archive got rid of their originals; but this does seem to have happened a lot elsewhere, and sadly Girona is one such case. From the state of the transcriptions, it is easy to think that this might be because they were already becoming hard to read, not just in terms of script though garbling does show that this was a problem, but also in terms of words being missed out, I presume because of fading. Anyway, the preservation is selective: whereas elsewhere in Catalonia and in Spain I would usually expect a tenth-century archive to be say, forty per cent sales, thirty-five per cent donations, fifteen per cent other stuff (wills, hearings, royal precepts, papal Bulls, letters, oddities), at Girona we basically only have precepts, Bulls and hearings.4 But the hearings are often kind of fun.

(Graph of documentary preservation from the county of Girona 785-884, by me, from my handout, more intelligible at full size and so linked.)

(Graph of documentary preservation from the county of Girona 785-884, by me, from my handout, more intelligible at full size and so linked.)

These too can be selective, of course. Have a look at this for the confusion of recording only what's necessary:

In the judgement of Viscounts Ermido and Radulf and also in the presence of Otger and Guntard, vassals of the venerable Count Unifred, and also the judges who were ordered to judge, Ansulf, Bello, Nifrid, Guinguís, Floridi, Trasmir and Adulf, judges, and the other men who were there in that same placitum with those same men. There came Lleo and he accused Bishop Godmar, saying that that same aforesaid bishop unjustly stole from me houses and vines and lands and courtyards that are in the villa of Fonteta, in Girona territory, that my father Estable cleared from the waste like the other Hispani, wherefore I made my claim before the lord King Charles so that, if it were so, he might through his letter order for us that the aforesaid bishop should return the aforesaid aprisio to me, if he were to approve. And while the aforesaid bishop, rereading, heard this letter, he sent his spokesman who might respond reasonably in his words in this case. Then I Lleo summoned that same mandatory of the aforesaid bishop, Esperandéu by name, because Bishop Godmar, whose rights he represented, stole my houses and courtyards and vines and lands that are in the villa of Fonteta or in its term, which I was holding by the aprisio of my father or I myself cleared, so that same aforesaid chief-priest did, unjustly and against the law. Then the above-said viscounts and judges interrogated that same above-said mandatory of the above-said chief-priest as to what he had to answer in this case. That man however said in his responses that he had his possession by legal edicts from that same Lleo, which that same Lleo had made before the above-said judges, that as for those lands for which the above-said chief-priest and his mandatory had previously appealed him, which are in the above-said villa, another man had cleared those houses from the wasteland and not him or his father, but whatever his father had or held in benefice in the selfsame villa or in its term, he had this from the late Count Gaucelm.  (The fourteenth-century building that replaced the Sant Feliu de Girona which was the ultimate beneficiary in this case.)

(The fourteenth-century building that replaced the Sant Feliu de Girona which was the ultimate beneficiary in this case.)

And while Esperandéu was presenting that profession in the court, that I Lleo had made and confirmed with my hands without any force, and it was found to be legally written, then I Lleo claimed before the above-named persons that Esperandéu brought this profession to be re-read by force, and that he made the claim of that same Lleo by force. I Lleo responded to myself and I said that in truth I had never been able to have [the properties]. Then they ordered my profession thereof to be written of the things which I Lleo have professed, and thus I make my profession that in all things the selfsame profession that I gave which that same Esperandéu showed in your presence here to be re-read in my voice, it is true about those selfsame things written there in all aspects and legally recorded, and I have confirmed with my hand, and neither today nor in any court can I prove that I made it under duress, but it is true thus just as is here recorded and the bishop did not take them from me unjustly by his same above-written mandatory already said, but the most venerable Charles, most pious king, for the love of God bestowed them upon Saint Felix, martyr of Christ, by his most just precept, which I have remembered, and so I profess. Profession made on the 11th day of the Kalends of February, in the 10th [recte twentieth?] year of the rule of King Charles. Signed Lleo, who made this profession. Signed Estable. Signed Guistril·la. Signed Receat. Signed Ansefred. Signed Lleo, who made this profession.

You see immediately the problem with the copying.5 Did Lleo also happen to be a scribe, and so sign off both as author and scribe? Or has the copyist just skipped a line and copied the same signature twice? Is there really a woman witnessing (not impossible—it's never impossible—but unusual) or could the scribe just not read the name that he's rendered as Guistril·la? Is the date right? If it's not, then we can identify the count whose vassals are turning up; if it is we have an otherwise unknown Count of Girona to deal with, assuming of course that the name is copied right...6

Also, of course, there is the bigger problem with just what the heck was going on? Here is the chronology of what Lleo seems to have asserted:

- Estable, father of Lleo, cleared some lands at Fonteta.

- Lleo also cleared some of the lands, presumably after inheriting.

- Bishop Godmar unjustly moved in on those lands, presumably expropriating Lleo.

- Lleo therefore went north to seek out King Charles the Bald, from whom he apparently got a letter ordering the bishop to do whatever was right.

- The bishop temporised by sending his man Esperandéu somewhere—to the royal court? to this trial?—to plead against Lleo.

- Lleo therefore makes this plea in the court right now.

Whereupon Esperandéu apparently produced a document by Lleo himself disclaiming any rights to the property, admitting that his father had never cleared it – though he held some land in the area that was from Count Gaucelm – and nor had he. Lleo next claimed (though the wording is extremely strange!) that this document was got from him under duress and then immediately (as the document has it) contradicted himself and admitted that his claim is fraudulent. So this is full of questions: what evidence did Lleo take to court? How did he ever think he could get away with this trial? Why did he give up? Was it the royal precept the document just happens to mention at the end? Was anyone actually taking Lleo seriously enough for that to be needed? And, the necessary alternative, may he actually have been stitched up? I have shown, repeatedly, that it was tough to be up against the Man in early medieval Catalonia. It may just be that Lleo had in fact made the first profession under some sort of duress, and then was duressed into making this one too. It doesn't look that way, admittedly, but it wouldn't, would it?

The thing is, we will never know because it wasn't thought important. There would have been another document, in which the actual proceedings of the trial were recorded, the different sides's statements, any proof that Lleo could bring (like a letter from the king for example).7 Because that document existed, Lleo's eventual profession and quit-claim, which is what we have, didn't need to record those details; we only get the ones it was important that Lleo himself said (such as that he had made the first document without any force and then claimed otherwise). On the other hand, when Girona's copyists got busy in the thirteenth century, if the trial record still existed, they didn't need it: this one names the property and makes it quite clear who lost the case and who got the land and where their claim came from (the royal precept mentioned right at the end, which the cathedral presumably brought in evidence, and which is still known, though it must have been younger than Lleo's father's time, again raising the possibility that there was more to Lleo's claim than he was allowed to admit).8 So the old one would have been one long document at least that they could not bother with, if they could even read it. It was probably binned with a sigh of relief, or put aside to be turned into book-bindings. And that's the way a lot of our source material has probably gone. Sobering, isn't it?

(Cross-posted at A Corner of Tenth-Century Europe.)

1. Santiago Sobrequés i Vidal, Sebastià Riera i Viader & Manuel Rovira i Solà (edd.), Catalunya Carolíngia V: els comtats de Girona, Besalú, Empúries i Peralada, ed. Ramon Ordeig i Mata, Memòries de la Secció Històrico-Arqueològica LXI (Barcelona 2003), 2 vols.

2. So, roughly 1200 documents in the above for four counties (I don't have it easily available to check, but of that order), as opposed to 1850 in R. Ordeig i Mata (ed.), Catalunya Carolíngia IV: els comtats d'Osona i Manresa, Memo`ries de la Secció histoòrico-arqueològica LIII (Barcelona 1999), 3 vols, covering only two counties and neither with their own counts.

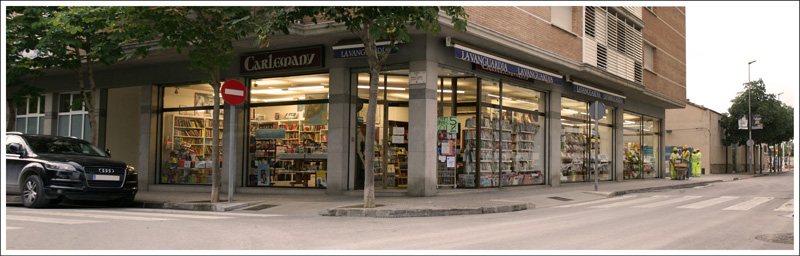

3. The main source of documents for Girona is the Arxiu Diocesà's Cartoral de Carlemany (see image towards the end), which contains no document featuring that ruler. It is edited by José Marí Marqués i Planguma as Cartoral, dit de Carlemany, del Bisbe de Girona (segles IX-XIV), Diplomataris 1-2 (Barcelona 1993).

4. I haven't actually done the brute maths here I confess, these percentages are just estimates, but Wendy Davies did the numbers for León in her Acts of Giving: Individual, Community, and Church in Tenth-Century Christian Spain (Oxford 2007), pp. 22-26 and they are comparable.

5. Sobrequés, Riera & Rovira, Catalunya Carolíngia V, doc. no. 30.

6. Ibid., pp. 83-84 for discussion of the dating and suggestions about the count.

7. For judicial procedure and the records we could expect in this area see Roger Collins, "'Sicut lex Gothorum continet': law and charters in ninth- and tenth-century León and Catalonia" in English Historical Review Vol. 100 (London 1985), pp. 489-512, repr. in idem, Law, Culture and Regionalism in Early Medieval Spain, Variorium Collected Studies 356 (Aldershot 1992), V.

8. The precept would be that edited by Ramon d'Abadal i de Vinyals in Catalunya Carolíngia II: els diplomes carolingis a Catalunya, Memòries de la Secció històrico-arqueològica 2 & 3 (Barcelona 1926-1955) as Girona II, of 834.