War games

One interesting minor theme of my recent museum visits here in London has been, I suppose, the popular origins of wargames (as opposed to the intellectual origins): I've been coming across a number of games, produced in the first half of the twentieth century and aimed presumably at children, which represent war in some way. War games, but not yet wargames. So for example, one exhibit in the Science Museum's aviation gallery was a First World War-era board game called Aviation: The Aerial Tactics Game of Attack and Defence. The board represents the sky, and the pieces are aircraft and squadrons. Here's the box:

According to the caption, it was published around 1920, and the cover shows 'stylised First World War tanks and Handley Page H.P. 0/400 [sic] bombers'. It doesn't look particularly like an O/400 to me; the corresponding game-piece is just called a Battle Plane (and the"tanks" are actually anti-aircraft guns on tank chassis, very advanced!)

The caption also says that the game itself was similar to Battleship. But as you can see above, each player can see their opponent's pieces, which is kind of exactly unlike Battleship (where the point is to guess where the enemy ships are). I'd suggest that since the pieces are blank on one side, it's more like Stratego, where you can see where the opposing pieces are, but not what they are. The pieces in Stratego have number values, and so do those in Aviation:

- Scout: 1

- Bomber: 2

- Bristol Fighter: 3

- Battle Plane: 4

- Troop Carrier: 4.5

- Airship: 5

- Three Battleplanes: 7

- Commodore's Squadron: 8

- Vice-Marshall's [sic] Squadron: 9

- Air Marshall's [sic] Squadron: 10

There are also some pieces which don't have any assigned values: Observation Balloon, Searchlight, and Anti-Aircraft Gun (3, 4 or 5 Miles). Presumably these correspond to some combination of the bombs, spies and flags in Stratego -- guns for bombs, searchlight for spies and balloon for flag might make sense, although there is also a double-square labelled"Aerodrome" on each player's side which doesn't seem to have any obvious correlate in Stratego (they are too far back to be choke points, maybe they are actually the flags?)

It turns out I could have saved myself the trouble with a bit of Googling: the third message on this Stratego website confirms that Aviation is a Stratego variant; or rather that both are derived from a common French ancestor patented in 1909, L'Attaque! Aviation came well before the American game, and its maker, H. P. Gibson, also published L'Attaque in Britain, along with a naval version (Dover Patrol) and an air-land-sea version (Tri-Tactics). In fact, Gibson's games were very popular and went through several editions into the 1960s. BoardGameGeeks has pages on all four of them, including photos of the components and even scans of some of the rules (for the later editions, though). So now it becomes clear that the enemy Aerodrome in Aviation is indeed the objective; you have to land one of your Troop Carriers on it to capture it. Interesting, but not exactly orthodox air strategy in 1920!

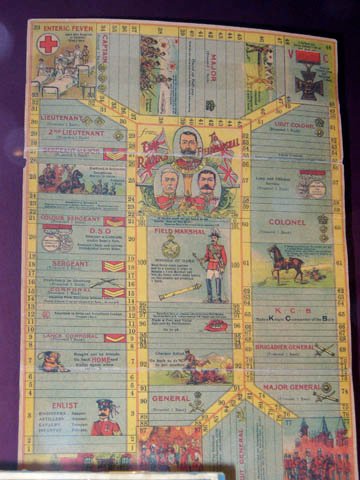

The Imperial War Museum had even more war-themed games on display. This one is called From the Ranks to Field Marshal, and is clearly basically Snakes and Ladders: you start out as a private, trooper, gunner or sapper, roll a die, move your piece along, and follow any instructions on the square.

Sometimes this is good ('Rescues a comrade under heavy fire. Promoted 1 rank, and receives Distinguished Service Order'), sometimes bad ('Court Martial. Tried for incompetence' -- 1 in 6 chance of being reduced 4 ranks). The first to land on 100 exactly becomes a Field Marshal and wins; though the game can end in other ways and then it's the highest ranked player who wins. The IWM's captions don't say much other than repeat the game's name, so I don't know when exactly it was published. It was in a case on"The military and naval origins of the [First World] War" but it was clearly actually made during the war itself, between 1914 and the end of 1915, as French is one of the field marshals shown in the centre, alongside Kitchener; presumably Haig would have been shown after 1915. Not that either French or Kitchener rose through the ranks to field marshal (who had by then? Wully Robertson didn't until after the war) of course, but it's interesting that the game does make you start at the bottom, instead of giving you a plum commission in the Hussars. So it seems like it's designed to appeal across the classes, and perhaps encourage young working-class lads to think they could make it to the top through hard work and straight shooting. (Though presumably the war would be over before the Snakes and Ladders-playing cohort reached military age!)

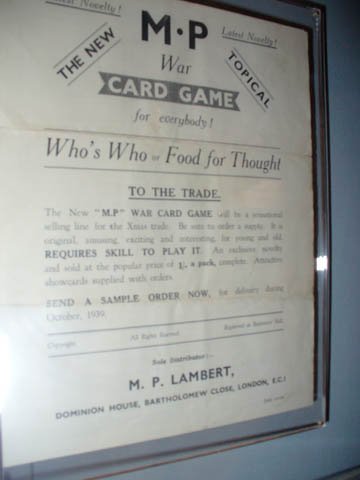

Moving on a world war, it seems that card games had become popular. It's harder to work out what the rules for these might be, but presumably they again were adapted from already existing games. The above is an advertisement aimed at retailers for a game called Who's Who or Food for Thought, ‘for delivery during October, 1939’, so quite likely was rushed into production just after the declaration of war.

OK, I think I've partly worked this one out: it looks like you have to try and collect triplets, where one card has an important figure's name, another has an incomplete sentence describing that person, and the last one has an illustration and word which completes the sentence, which cleverly rhymes with the word in bold on the second card. So for example: 'Winston Churchill'/'Shows he is the true fighting type, ignoring all Nazis [sic] scandalous'/'Tripe' (and there's a picture of some tripe -- I assume). Sounds pretty trivial -- I think I'd rather be playing From The Ranks To Field Marshal, to be honest!

This one is called Evacuation, I would guess from the first evacuation at the start of the war rather than the one during the Blitz, but can't really be sure. There are at least three types of cards: Householder, Evacuee and (I think) Teacher -- though the Evacuee cards seem to be subdivided with the red letter in the corner: B, G, M and perhaps A). Each has a comic figure -- Mona Mudd is one of the evacuee children, for example, who has fallen into a puddle. Possibly, then, the game is depicting in light-hearted fashion the difficulties everyone involved had in adjusting to the new living arrangements.

But to return to the First World War period, and to board games, the most intriguing game out of all of these is War Tactics or Can Great Britain be Invaded? This time I've manage to find it in the IWM Collections database, as EPH 2701 and EPH 2702, and there it is dated to c. 1911. My initial thought was that it was from during the war, but on balance, I'd probably agree with the comment there that it reflects 'the production and widespread popularity of anti-German ‘war scare’ literature of the period'.1

The pieces here are Dread Nought (3 dots), Cruiser (2 dots), Torpedo Boat (1 dot), Sub, an unnamed piece which is obviously a monoplane, and one which has 16 dots on it and no picture -- I'm guessing this is meant to be a ground unit. But what is most intriguing is the map:

The thing about Aviation and the other Stratego-style games, along with other stylised representations of warfare like chess, is that they are almost completely symmetrical. No matter which side you're playing, the board is the same, the forces are the same and the objective is the same. About the only asymmetry is that somebody has to go first. This does make such games very evenly-balanced, and so the result will on balance come down to skill. But as a representation of warfare, it's not in the least realistic (except in certain circumstances, particularly the more tactical you go, I guess). Each side in a battle or war has very different forces at its disposal, in terms of numbers, equipment, training and morale. And each side will be constrained by the geography it has to fight from or in, and each side will likely have different objectives in the war. Abstract games like chess or Stratego don't have asymmetry, which is why they might be war games, but aren't really wargames as currently understood.

But the map for War Tactics is clearly very asymmetric, as it's based on the actual geography of the North Sea. Naval bases are placed not to make a"good" or"fair" game, but because that's where they really were. The eastern coast of England does look inviting for the Germans because of the lack of bases, but then the British cities are spread out both north and south: which way to go? It also looks like the British can try to invade Germany, but good luck getting in close to the German coast. I'm not saying this is a particularly accurate depiction of the North Sea strategic situation ca. 1911 -- for one thing it does look like the German and British forces might be symmetric in number and capability, which is rather unhistorical; and anyway I don't know what the rules are -- but it is at least a partial recognition that not all is fair in war, just as in love. So some props are due Lowe and Carr of Belvoir Street, Leicester, for creating an early ancestor of the strategic wargame.

I was going to leave it there, but I came across a couple of things on the net that I have to mention. One is from a Time article published on 14 December 1942, about the current vogue for military games. It talks about Gibson and the French origins of L'Attaque, but says he independently came up with Dover Patrol. It also mentions that the industrial designer Norman Bel Geddes -- who also rather liked very big aeroplanes -- invented his own Little Wars-style wargame played on a huge table with 14 (!) players a side. Games could last for years -- if you had the right stuff, that is:

The game occasionally took a tragic turn. Rear Admiral William B. Fletcher, long a regular player, lost eight capital ships one night and was so humiliated that he never returned. Another friend, after being court-martialed one evening for losing an entire army, lay on a sofa and cried.

Such are the burdens of command.

The other interesting thing I came across was that Dennis Wheatley, the best-selling author of thrillers in the 1930s who went on to write strategic appreciations for the Joint Planning Staff during the war (his Times obit claims it was his idea to remove all the signposts in Britain!), invented several strategy games which appear to be at least geographically asymmetric. One, called Invasion, was published in 1938, and was popular enough to go through a few editions. The publisher's description is as follows:

ATTACK & DEFENCE by Land, Sea and Air A thrilling battle of wits in which 2, 3 or 4 players have as their playing pieces the armed forces of the Navy, Army and Air Force. The Battlefield is a Map in the size of approximately 24 inches square, PRINTED IN SIX COLOURS with Capitals, Principal Towns and Forts named and a full Fighting Force of 160 Pieces with dice, shaker, etc. You have to be ready to resist an invasion and at the same time send Expeditionary Forces to Allies. A Game in which Young and Old can use their strategy to overcome the luck of the dice.

There's a picture of the map here; it appears to be a Ruritanian representation of north-west Europe (the country off the coast is called Angleland, I think). It's interesting that this came out in 1938; I can't say I'm aware of much discussion of the possibility of an invasion of Britain at the time. But since Wheatley was helping plan anti-invasion strategies a couple of years later, Invasion perhaps should be considered as serious speculation, and not just a game.

Finally, just for completeness' sake, I'll mention two other war games I came across. From 1916 or so, there's Trencho, 'The Famous Australian War Game As Played in the Camps and Trenches', which is apparently just Nine Men's Morris. Can't say I've ever heard of it, but"Trencho" does sound very Australian! As does Spotto!, for that matter (second from the bottom), and indeed judging from the web it was originally a Bingo-like Australian car journey game (make lists of things to watch out for, cross them off when you see them, then shout"spotto!" when you've got them all). But again, I've never heard of it. This one is an aircraft recognition version, 'OF INSTRUCTIVE VALUE TO: SPOTTERS, A.T.C.[,] R.O.C.[,] HOME GUARDS, SCOUTS, A.R.P., POLICE, SAILORS, SOLDIERS, AIRMEN, Etc.' so obviously it's British, ca. 1940, and not Australian -- anyway, we didn't get many Heinkels down our way!

My brain is fried after all that, but one last thought. Some of these games are evidently intended to be simulations of war, not just representations in some abstract way: War Tactics asks in its title," can Great Britain be invaded?" and presumably players are invited to think that the game does provide an answer to that question. Did they in fact think so? And if so, did their game-playing affect their fears about the future one way or the other? If the German player in War Tactics won 7 times out of 10, did the players (presumably children) take that as a warning of what may come? Or did they just treat it as a harmless bit of fun? No doubt some did see it as just a game, but possibly not all. As a teenaged wargamer, one of my favourite games was GDW's The Third World War, about the potential land and air war in Germany between NATO and the Warsaw Pact, ca. 1985. It was considerably more sophisticated than the proto-wargames discussed here, but not necessarily more accurate. I certainly thought it was, to some degree, accurate, however. Playing such games was one way in which I tried to understand the Cold War and what might happen in the future, and I do remember getting anxious when the Warsaw Pact won. I wanted NATO to win, because I would want NATO to win in a real war if it ever happened. In fact, I must admit I would sometimes cheat a bit in solitaire games, re-rolling die rolls in important battles to get a"fair" result. Pretty silly, any way you look at it; but I could understand some overly-sensitive boy in 1911, probably already immersed in le Queux and An Englishman's Home, playing War Tactics and thinking that perhaps"Der Tag" was nearly upon him ...

- For example, looking at the map, Norway, Sweden, Denmark and Holland are marked as neutrals, whereas France and Belgium seem to be British allies; this suggests a WWI setting. Except that Luxembourg is also neutral, and most of Belgium's territory should be marked as a German conquest. Perhaps more tellingly, there's no naval base at Scapa Flow -- the closest is Cromarty (ie Invergordon). Given the great importance of Scapa Flow as the harbour for the Grand Fleet throughout the war, it's hard to imagine that it would have been left out.