Why Don't Americans Like the United Nations?

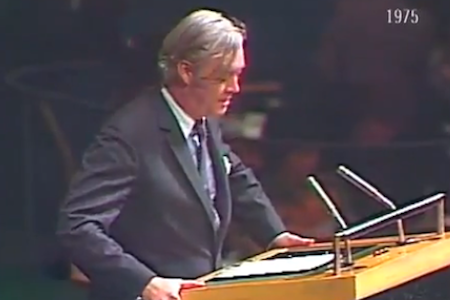

U.S. ambassador to the United Nations Daniel Patrick Moynihan speaking against the "Zionism is racism" resolution in 1975. Credit: YouTube.

Last week’s United Nations General Assembly vote upgrading the status of Palestine was a dramatic moment, with the United States courageously voting in a small, beleaguered minority. Yet it seemed to evoke one big collective American yawn. Yes, we have our own troubles with the fiscal cliff and the Sandy aftermath, while watching even bigger Middle East threats as Egypt risks imploding and Syria risks exploding. But the national dismissal also reflected the fact that most Americans do not take the U.N. seriously anymore. The great redemptive hopes generated when it was founded in 1945 soured so long ago that, like embittered divorcees, most Americans have forgotten they -- or their grandparents -- were ever in love.

Last week’s United Nations General Assembly vote upgrading the status of Palestine was a dramatic moment, with the United States courageously voting in a small, beleaguered minority. Yet it seemed to evoke one big collective American yawn. Yes, we have our own troubles with the fiscal cliff and the Sandy aftermath, while watching even bigger Middle East threats as Egypt risks imploding and Syria risks exploding. But the national dismissal also reflected the fact that most Americans do not take the U.N. seriously anymore. The great redemptive hopes generated when it was founded in 1945 soured so long ago that, like embittered divorcees, most Americans have forgotten they -- or their grandparents -- were ever in love.

In my new book, Moynihan’s Moment: America’s Fight against Zionism as Racism, I look at November 10, 1975, which I identify as the day the U.N. died, the day Americans -- and many other Western democrats -- lost faith in the United Nations. The frustration had been mounting for years, as the General Assembly, pushed by Soviet manipulators, turned into the Third World dictators’ debating society. One indicator, that Paul Kennedy notes in his book on the U.N., is that for the first quarter-century of the U.N.’s existence, until March 1970, the United States never vetoed any Security Council decisions. But the Soviets did, with 79 "nos" in the first ten years earning the Soviet delegate Andrei Gromyko the nickname "Mr. Nyet." After 1970 the records reversed. The Americans started vetoing and the Soviets no longer needed to.

Still, popular opinion had not been galvanized against the United Nations. But when Daniel Patrick Moynihan became the U.S. Ambassador to the U.N. in the summer of 1975, this articulate, visionary, New York street kid turned Harvard professor and policy wonk insisted that the United States had to learn to fight in diplomatic forums.

When the Ugandan dictator Idi Amin was feted in Turtle Bay, Moynihan boycotted the dinner and called him a “racist murderer.” The resulting diplomatic brouhaha had the civil rights activist Bayard Rustin, the national chairman of Social Democrats USA, wondering why the U.N. delegates seemed more outraged by Moynihan’s condemnation than by Amin’s crimes.

The next month, when the Soviet-Arab alliance pushed through Resolution 3379, declaring Zionism to be a form of racism, Moynihan’s eloquence united Americans left and right, black and white, Jews and non-Jews, in fury. Moynihan’s indignation attracted bipartisan approval, from liberals such as Senator Frank Church, Eldridge Cleaver and Cesar Chavez to conservatives such as Senator Barry Goldwater, the economist Milton Friedman, and Ronald Reagan. “Did I make a crisis out of this obscene resolution?” Moynihan would bellow, responding to criticism that he picked a fight. “Damn right I did.”

Moynihan’s anger was patriotic but not personal, populist but not partisan, offering confident leadership when most leaders dithered. The aftershocks from Moynihan’s defiance anticipated broader shifts in American politics and culture that would shape the 1980s Reagan Revolution, while marking the loss of most Americans’ respect for the United Nations. He paved the way for a more muscular, idealistic, foreign policy, one which began to be called “neoconservative” -- a label Michael Harrington had popularized, starting in 1973 -- and one which Moynihan rejected his entire public life as "coined in epithet." Remembering Moynihan’s eloquent defense of America and its foreign policy, along with the enthusiasm it generated, adds nuance to the simplistic narrative of the "Morning in America" 1980s by suggesting that the 1970s were not as defeatist as many recall today. Historians are recognizing that America’s rightward shift began in the 1970s. Reagan himself acknowledged that America’s patriotic spirit had begun to revive even before his 1981 inauguration.

For the many Baby Boomers who were raised trick-or-treating for UNICEF and participating in Model U.N., the disillusion with the U.N. was distressing, another blow to their once-innocent worldview. Moynihan’s politics of patriotic indignation inspired many, including Ronald Reagan, who attracted loud applause when quoting Moynihan’s speeches during the 1976 presidential contest -- which he narrowly lost to the incumbent Gerald Ford. With mixed emotions, the liberal commentator Max Lerner noted that riding this “wave of nationalist feeling” made Moynihan a “hot political property.”

By the 1990s Moynihan was vindicated, even though as senator he often broke with President Reagan. The Soviet Union fell. More and more politicians left and right echoed Moynihan’s politics of patriotic indignation. In 1991 the General Assembly revoked the “Zionism is racism” finding. Newly freed Eastern European countries apologized for collaborating on this Cold War relic. Moynihan’s “standing up and being responsible for the rescission of the Zionism is racism resolution of the U.N. was an act far more important than anything I have done,” New York’s mayor Ed Koch would say. Two years later, Israelis and Palestinians embraced, if awkwardly, on the White House lawn, seeking peace through the Oslo Accords.

Yet now, a decade after Moynihan’s death in 2003 at the age of seventy-six, and nearly forty years after Resolution 3379 passed, America and Israel seem to be reliving the 1970s. In the traditional oscillation between realism and idealism in American foreign policy, the idealists are flagging. President George W. Bush’s ideological, confrontational stance, followed by economic recession, has led many Americans to doubt America’s clout, repudiating both neoconservatism and Woodrow Wilson’s faith in disseminating democracy worldwide, which Moynihan shared. The Israeli-Palestinian stalemate looks chronic. And what Moynihan called “the big Red lie,” that Zionism -- a nationalist movement like hundreds of others -- is racist and creating a form of apartheid -- when the Israeli-Arab conflict is a national not racial struggle -- seems more ubiquitous than ever.

Popular memory -- even of dramatic water-cooler moments that captured the nation’s attention and sparked many conversations -- is fickle. Some historical events, like cataclysmic earthquakes, destroy contemporary structures, rattling everyone. Others may not register as high on the historical equivalent of the Richter scale, even as they transform the topography while leaving significant fault lines. Just as they forget boom times during economic busts, many Americans lost faith in the U.N., with fewer and fewer remembering its initial promise. Resolution 3379 is not as well remembered today as the Yom Kippur War, which preceded it, or the 1978 Camp David Peace Accords between Israel and Egypt, which followed. But its aftershocks nevertheless persist with surprising strength.