Why (and How) FDR Ran for His Third Term

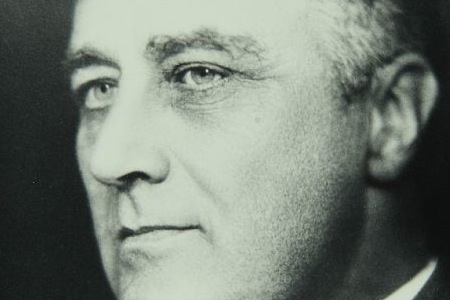

Credit: Flickr.

Throughout American history presidents have brought very different decision-making styles to the White House. George W. Bush once said he was not a “textbook player” when it came to decisions but rather a “gut player,” while Barack Obama has said he makes decisions “based on information and not emotion.” One observer has described our current president’s style as “defiantly deliberative, methodical and measured.” But Franklin D. Roosevelt was in another class altogether when it came to decision-making, and never was this more evident than when the famously social but obsessively secretive president considered whether to run for an unprecedented third term in 1940.

Throughout American history presidents have brought very different decision-making styles to the White House. George W. Bush once said he was not a “textbook player” when it came to decisions but rather a “gut player,” while Barack Obama has said he makes decisions “based on information and not emotion.” One observer has described our current president’s style as “defiantly deliberative, methodical and measured.” But Franklin D. Roosevelt was in another class altogether when it came to decision-making, and never was this more evident than when the famously social but obsessively secretive president considered whether to run for an unprecedented third term in 1940.

Many close observers believed at the time that FDR had long before decided to run again; it was obvious, they concluded, that this man of outsized ambition would find a way to remain in the job he loved. Many historians and biographers have concluded as well that the decision was inevitable. The only thing we know for sure about FDR, Roosevelt scholar William Leuchtenburg has said, is that he never left the presidency voluntarily.

But in fact the decision was far from inevitable. President Roosevelt never challenged the wisdom of the sacrosanct two-term tradition. On the contrary, as his second term wound down, he made specific plans to retire to his beloved Hyde Park in January of 1941. He had already designed and begun construction on his presidential library there to serve as his retirement headquarters, and he had built a small private retreat not far away. Every time he returned to Hyde Park during the spring of 1940, he brought boxes of papers and artifacts for the library. Colliers magazine had persuaded him to sign a lucrative three-year contract to write regular articles, and FDR had in turn persuaded two of his closest aides, Harry Hopkins and Sam Rosenman, to move to Hyde Park to help him with that task as well as with his memoirs. Roosevelt strongly felt the need to replenish the family finances and to recover his health. Unbeknownst to nearly everyone, he had suffered a mild heart attack in February, and the sedentary life required of a polio victim had taken a huge, but largely unseen, toll. As he told a number of visitors, he was tired and he wanted to enjoy what time he had left.

When war began to loom, however, FDR began to hedge on the issue: he would only consider running for another term, he told a few confidantes, if Nazi aggression in Europe exploded into a major shooting war and if there was no one else who could step in. This became his caveat, his qualifier, although he never stated it publicly. In fact, during the second half of 1939 right up until the Democratic convention in July 1940 he said nothing publicly on the matter. Whenever a reporter tried to question him on his intentions, Roosevelt told him to put on a dunce cap and stand in the corner or he found another way to laugh off or ignore the question. Journalists and cartoonists began depicting him as a “sphinx” who wouldn’t reveal his secrets.

FDR’s method of making decisions, especially large and difficult decisions, was to put off making them as long as possible. Sometimes, he found, the issue would solve itself and disappear. Even if it didn’t, he would almost certainly have more information on which to base his decision if he waited, and in any case the longer he waited the longer he would control the situation. In this case there was an even more compelling reason to remain mute. If he announced he intended to retire, he would immediately become a lame-duck whom foreign and congressional leaders could ignore with impunity; at his core FDR was a man of action and he abhorred the idea of irrelevance. And if he said he was open to a third term, he would be denounced as a “dictator,” a term that was already in the air, and everything he said or did would be seen through a political prism. So he remained silent.

Although early on he had encouraged others to seek the Democratic nomination -- Harry Hopkins and Secretary of State Cordell Hull chief among them -- Roosevelt’s “sphinx” stance inevitable discouraged others from getting into the race because they didn’t know what he would ultimately do. He thus effectively froze the field and in the end presented Democrats with a Hobson’s choice: they could choose anyone they wanted, as long as it was Franklin Roosevelt.

The other chief aspect of FDR’s decision making was its solitary nature. There is no evidence that he spoke candidly with another soul, not even his wife Eleanor, about the third-term question; he knew she wanted him to retire, and she didn’t believe that her personal views should matter on a question of such huge importance to the country. He had no real confidantes, she wrote later, not even her.

In the end he was persuaded to run again when Hitler launched his blitzkrieg on the Low Countries and France, and he couldn’t find another Democrat who both supported his policies and who could win the election. It was not until four days before delegates convened in Chicago to nominate their candidate that Roosevelt laid it all out to someone he trusted. He called Felix Frankfurter down from the Supreme Court for a two-hour conversation on whether he was justified in seeking a third term. In the face of the “unprecedented conditions” facing the country, Frankfurter assured him, he was not only justified in running but, as the most experienced and able person to see the country through the crisis, he had a duty to run.

And so, virtually alone and at the last minute, he made one of the most consequential presidential decisions of the twentieth century, if not in all of American history.