Investigating the Theft of the American Dream with Hedrick Smith (INTERVIEW)

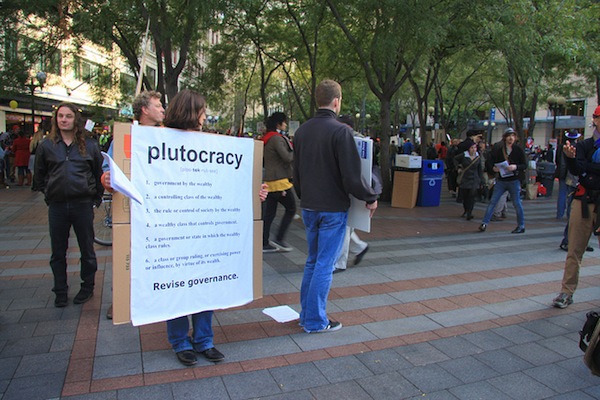

In his provocative book, Who Stole the American Dream (Random House), Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Hedrick Smith explores the historical context of our present political and economic situation in an America that has become a modern plutocracy run for the benefit of the richest few while increasing inequality and immobility limit the aspirations of most citizens.

Based on extensive research and interviews with experts as well as people who have suffered the cruel reality of division, unfairness and neglect, Mr. Smith details the policies and decisions of the past forty years that have fostered a modern Gilded Age, forsaken the foundations of post-World War II prosperity, and created “Two Americas ... divided by power, money and ideology.” He explains how deliberate strategies have led to today’s gross inequality of income and wealth.

With outsourcing, business shutdowns, tax breaks for the rich, corporate slashing of medical benefits and pensions, and other changes, Mr. Smith contends that the American Dream has been stolen and the middle class has stagnated as the government has become an enabler of the rich and as ideological conservatives have pursued the politics of gridlock.

Mr. Smith’s book brims with statistics, facts, and the comments of scholars, but it also depicts the human face of an America wounded by a financial culture driven by greed and by a political culture dominated by wealthy interests, leaving average citizens marginalized and bearing the brutal consequences.

Journalist Jim Lehrer wrote of Who Stole the American Dream: “It almost seems to tame to call this simply a book. It is an indictment that is as stinging, stunning and important as any ever handed down by a grand jury.” The book earned a starred rating in Kirkus Reviews with the comment that Mr. Smith presents “... one of the best recent analyses of the contemporary woes of American economics and politics.”

Hedrick Smith, one of America’s most esteemed journalists, is a bestselling author and a prize–winning reporter and documentary producer. His books include The Russians, The Power Game: How Washington Works, and The New Russians, among others. As a reporter at The New York Times, Mr. Smith shared a Pulitzer Prize for the Pentagon Papers series and won a Pulitzer for his international reporting from Russia in 1971–1974.

Also, Mr. Smith’s documentary work has won many of television’s major awards. Two of his Frontline programs, The Wall Street Fix and Can You Afford to Retire? won Emmys and two others, Critical Condition and Tax Me If You Can were nominated. Along with the George Polk, George Peabody and Sidney Hillman awards for reportorial excellence, his programs have won two national public service awards. And, for more than 25 years, Mr. Smith was a principal panelist on Washington Week in Review and as a special correspondent for The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer.

Mr. Smith recently talked by telephone about his book and the grave situation for many Americans, as well as his ideas to restore the American dream.

* * * * *

Robin Lindley: What inspired your book Who Stole the American Dream and your desire to look into the history of how this theft occurred?

Hedrick Smith: I began work on the book in the fall of 2009. Like everybody else at that time, I was troubled by what had happened to America: the financial collapse, the housing boom and bust, all of the foreclosures, the rising unemployment, the fear that we were in for another round of depression -- not recession. I had done a number of PBS documentaries and mini-series on subjects such as Wall Street, Wal-Mart, off-shoring of jobs, healthcare, and retirement, but I had never tackled the housing sector.

So I was interested in understanding the housing bubble and bust, and that led me into the banking system and how it works and the Wall Street collapse. As I came to understand what was going on, I saw parallels with the work I had previously done on healthcare, on retirement, on job off-shoring, on global competition with Asia and with Europe. I began to see a pattern and I decided I needed to do something bigger, to go beyond the housing issue and look at what had happened to the economy and the middle class in general.

I knew that our problems went back further than the collapse itself. It didn’t all begin in 2007 or 2008. My reporting and research led me back to the 1970s as the watershed time when we moved from one era to another in America, and I believe we are still living in that era today.

The concept of the book evolved. I signed a contract with Random House to write a book called The Dream at Risk. Only after two and a half years of research and reporting did I come to the conclusion that literally the dream had been taken away from average Americans by the financial elites, the power elites in Washington, by big business, and by certain policy makers who may not have been out to hurt the middle class but in conceiving policies that helped big business and the Wall Street banks, they severely damaged most Americans: the middle class, the working poor and even some of the upper middle class.

It’s fortunate that you were able to go back and explore the history of this complex situation. What do you see as the “American Dream” and how did going back in history help you understand the dream?

In the fifties, sixties and seventies I had the personal experience of seeing the middle class share in America’s general prosperity. I had seen middle-class political movements and bipartisan government work. So I had a pretty good idea that most Americans were doing reasonably well in that era.

After going back and looking at what it meant that most Americans were doing well, I got a clearer picture of the American dream, which to me is fairly simple.

The dream of most Americans is to have a job, to have a steady rise in income over your lifetime as you build up your skills, to have security in your job, to have some health benefits from your employer, to have a retirement benefit from your employer plus Social Security, to make enough money so you can afford a down payment and make the monthly payments on your home. It’s the job, it’s health care, it’s the pension, and then owning a home and the hoping for a better future for your kids.

Some Americans who think of the Horatio Alger story want to go from rags to riches, but that’s much more individual and it’s much more rare now. Then you have the immigrant dream that you come from somewhere else -- Greece, Albania, Vietnam, Turkey, Central America, or wherever -- and you live a better life in the U.S. than you lived back there.

Your historical findings are fascinating. You trace the origins of the situation now back to an early 1970s memo by Lewis Powell, a business attorney who was appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court by President Nixon. Why was this memo so significant?

It was a surprise to me, particularly because I was the Washington bureau chief of The New York Times in the 1970s, and the chief correspondent well into the eighties. Like many other people, journalists or not, I had thought the changes began in the 1980s under Ronald Reagan and with the return of Republican Party control of the Senate, and Reagan’s two terms followed by the first Bush.

So it was a surprise to me that the pivotal moment came in the late 1970s under my watch at The New York Times . We had seen some of the symptoms, but we didn’t understand the causes. At that time, I was more involved in national security and foreign policy coverage than domestic economics and politics because of my experience as a foreign correspondent. But I don’t remember economic stories that explained the degree to which business lobbies had moved in powerfully in that period. And I never heard the congressional reporters saying that there had been a major power shift in favor of business on Capitol Hill - to the detriment of policies for the middle class.

It was a discovery to me to find out two things. Number one, that Lewis Powell, a famous corporate attorney who was later put on the Supreme Court by Richard Nixon in 1972, was such an ardent advocate for the free market system that he became a Paul Revere for a political revolt by business leaders. Powell was alarmed by what he saw as threats - the power of labor unions, the consumer movement, the women’s movement, the environmental movement and government regulation of business, largely propounded by the Nixon Administration. He saw all of these as a threat to the very survival of American free enterprise.

Today, the memo Powell wrote in 1971 looks like considerable exaggeration. He saw business on the political defensive, said they were in dire straits and in danger of seeing the free enterprise system go down the tubes. I don’t think so. It was not like the Depression or like Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal when businessmen warned that we were becoming a socialist country.

But Powell was alarmed and he wrote a powerful, moving memo saying that the businessman was the forgotten man. Although business was doing well economically, Powell wrote that free enterprise was being beaten terribly in the political arena. Business had to learn from the union movement and get politically aggressive, Powell contended - identify its enemies, organize, move lobbyists into Washington, take the high ground, create a long-term political plan, feed it with money, and take charge.

The second thing that astonished me is that’s exactly what happened. It’s not that Powell was that powerful an individual voice. But when the U.S. Chamber of Commerce privately circulated his memo to business leaders around the country, that gave Powell’s call to action credibility, strength and support.

By the early 1970s, many business leaders, particularly in the Sun Belt -- as you saw with the rise of Barry Goldwater in the 1964 campaign, were chafing at the power of the trade union movement, the consumer movement, the women’s movement, and the environmental movement.

Powell’s memo set things off. Within seven or eight years, before Reagan was in office, they had rallied what I call “Powell’s Army.” There were 9,000 registered corporate lobbyists. There were 2,425 companies that had offices in Washington, compared to only 175 when Powell wrote his memo. There were 50,000 people working for business trade associations. This was a veritable army of lobbyists that were organized and focused and they began to turn policy around -- under Jimmy Carter, to my surprise.

Carter was in trouble because as president he was not able to get his way with Congress, even though the Democrats controlled both houses. He was not a very effective political leader. And business groups won many victories, with legislation creating the 401(k) plans and making changes in the bankruptcy laws that favored corporate management. These were policy wonk issues, but they were very important. What we didn’t understand at the time was that they were symptoms of a change in the political tide of American history.

The landscape of power was changing and business was able to fight for and get the legislation it wanted. At that time, there was a push by Democrats to index the minimum wage so that there would be automatic raises as inflation went up. Business lobbyists blocked that. There was a move by labor to get laws to make it easier for trade unions to organize. Business lobbyists blocked that. Jimmy Carter wanted to change the tax system by closing loopholes for the wealthy and raising corporate taxes. Business lobbyists blocked that, and they moved taxes the other way, getting Congress to drop corporate tax rates and drop the capital gains tax rate and keep loopholes for the wealthy.

When you go back today and look at the success of the business lobbyists, you can see that period, that session of Congress, was a political watershed. From the New Deal up to that period, 1978-1979, policies had generally moved in one direction, to expand safety nets and regulate business. Then, it was as if the tides shifted and went into reverse. I didn’t understand that until I did the research for this book. And when it hit me, it struck me as a really important personal discovery and as a place to start this book because that’s where our story today begins.

The role of Lewis Powell was a surprise to me. You’re a renowned journalist and historian. How did you go about your historical research for your sweeping examination of our economy and politics over the past four decades?

I read a lot of scholars and other authors. I learned a lot from historians. I found things in different places. I found references to the Powell memo, read more and more about it, and began to realize its importance.

Research and reporting are often like a cat with a ball of twine. You pull on a string and it leads you somewhere new. Some very good political scientists in academia by the late 1990s began to understand the shift that had taken place and the importance of the Powell memo, and they wrote academic studies. A lot of the data that I gathered on the growth of the business lobby came from academic work by good scholars who had checked the records of Congress to find the numbers of registered lobbyists and the numbers of trade associations. Like other writers, I stood on the shoulders of other people who did good research.

Then I had the benefit of knowing some of the important historical players -- Ray Marshall, Carter’s secretary of labor; former House Speaker Newt Gingrich; former senate Majority leader Bob Dole; White House officials in the Reagan and Clinton Administrations. I knew people in business who had been sources of mine, and I went back and talked some of them. When I got into how the 401(k) got slipped into the tax code, I knew about that from reporting for my PBS documentary Can You Afford to Retire? I vigorously researched the history of the 401(k), and I knew people in the retirement analysis field and talked to them, so I could flesh out the story.

It’s a combination of classic journalistic field work or reportorial work: getting a clue, building on it, calling a source, that source leads to another and you flesh out more of the story. Then reading the historical record, including Congressional hearings dealing with legislation and so forth.

Some of it is flat out quoting or citing research done by others. It’s a book with more than a thousand footnotes. You can tell how much I relied on the work others had done.

In the journalism of the time, there was a smattering of coverage of the issues that I discuss in the book. But journalists didn’t see or understand the pattern back then. And if you don’t see the pattern, you don’t know how to connect the dots. But when you go back and see events through a prism with some insight and you know where to look, you can find significance in details that you hadn’t noticed before.

So it’s trial and error. It’s a little bit like drilling for an oil well. You think you have a story, a find, if you will, and you develop it. It could be a dry hole or a good hit, and sometimes it takes a turn in a different direction, and you simply have to follow where it leads.

And you also did many interviews with people who are directly affected by the shift of wealth to the very rich.

I’m glad you brought that up. I think that’s one aspect of this book that makes it very different from some excellent academic books written by economists like Bob Reich at UC Berkeley or Joe Stiglitz at Columbia or Paul Pierson at Berkeley and Jacob Hacker at Yale, all of whom I benefited from reading.

I had plenty of experience with average Americans out across the country who had gone through the personal struggle of this wrenching change in their personal economic fortunes and had experienced deep economic losses firsthand. In many cases, I had interviewed them in the 1990s or early 2000s. I went back to them years later, and sometimes to the towns they lived in or to factories where they had worked, to find out what had happened. Having that historical continuity in their personal lives strengthens the narrative of the book.

It’s not just analysis and data but it’s also a zoom lens into individual people’s lives - not just for a moment, as in daily journalism, but over years of covering them in the past and coming back later to see how they were faring - finding that some people were unemployed or bouncing around from one job to another. Maybe a pension wasn’t being paid and they had to go back to work in their seventies. The stories I could tell based on years of reporting, enrich the book and make it more human and compelling.

You comment to the effect that many people who are doing all right now don’t appreciate the suffering that others are going through. I talked recently with Zoriah Miller, a photojournalist, about his stunning photographs of people in Detroit who are surviving by scavenging metal from abandoned buildings at great risk to themselves. The scenes are haunting and other worldly -- and it seems a story out of an extremely impoverished developing area, not the U.S. Do you see a lack of empathy or indifference to the poor as part of the polarization of the country you describe?

To me, there are two Americas. There’s the one percent and the 99 percent. The one percent are off the charts financially and don’t even see the other America. They’re so far from everybody else that they’re almost a separate country.

But the Two Americas are not extreme rich and poor. It’s those who have enormous plenty and people in the middle who don’t have enough. I was struck by a poll done by the Pew Center for Media and the People on experiences during the recession. The headline on it was revealing - “One Recession: Two Americas.” What they found was that everyone had stumbled in some way from the recession. For people of extreme wealth, their luxury homes, their stocks and their yachts were worth less. And for the upper middle class, their stocks and their houses were worth less, too, but they were still doing okay. They still had their jobs, they had their income, and they hadn’t been foreclosed out of their homes. Their kids were still headed for college. Basically, they didn’t have to adjust their lives very much.

But another half of the country had a totally different experience. People were either thrown out of work or cut back and put on part time. Or they were foreclosed out of their homes. They lost their health insurance coverage. If they had a 401(k) through their employer, the employer stopped contributing to the 401(k), plus they couldn’t afford themselves to make any contributions to it. They were going into debt. They were borrowing from relatives. They were foregoing not just a Friday night out or a movie. They were foregoing healthcare. They wouldn’t see the doctor because they couldn’t afford it. They weren’t buying prescriptions because they couldn’t afford them. Or, if they got their prescriptions, instead of taking four pills a day, as they were supposed to, they took one a day. They scrimped in every imaginable way to try to get by.

I don’t think these Two Americas understand each other at all, particularly the better-off one. I remember thinking on Saturday nights in Bethesda, Maryland, near where I live, seeing restaurants jammed with people who were having expensive meals and not hesitating to buy an expensive wine and have a nice dessert. There was no cutback visible, and yet this was exactly at the time when unemployment was skyrocketing over 10 percent officially, but probably much more like 20 percent, if you count people who had dropped out of the work force or were forced into part time work.

Those were totally different worlds. That world I was living in -- that upper- middle-class-successful world of professional people -- was doing well in the midst of a recession. Yes, some couldn’t afford the trip to Europe or Galapagos or Tahiti, but they weren’t giving up anything essential. The other part of America was hurting painfully and this poll laid out the gulf between those two worlds.

I think we still have this problem today. I don’t think those of us who were fortunate enough to have a good education, steady work, live in nice homes in nice communities, and go to the theater and the opera, and take summer vacations, have any idea of what it’s like for the couple who works four jobs between them and one has a two-hour commute, and they can’t find time to buy groceries, and they’re just skimming along. I don’t think we understand what it feels to live that way. I think that’s a tragedy and I think our policies are defective in part because we are so divided, so separate from each other.

Speaking of division, Wisconsin Republican Governor Scott Walker spoke to a conservative group in Seattle on September 5, 2013. Outside the event, pro-union and progressive picketers greeted attendees of this Washington Policy Center event. In introducing Walker, supposedly moderate Republican and former U.S. Senator Slade Gorton told the gathering that the picketing they ran into “is the reaction of losers.” This seems an illustration of the divide you describe.

We got that from Mitt Romney in spades. There’s that attitude of people who have been successful, especially the newly rich in America. “I made it, and therefore it’s your fault if you didn’t make it. Anybody can make it in America.” That’s simply not true.

We are no longer the land of opportunity. If you grow up in Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Finland, Germany, France, Australia, New Zealand, Canada -- it’s easier to move up the ladder than it is in America. Statistics demonstrate that. People are handicapped in the U.S. by who their parents are, where they live and the quality of schools they go to. Experts talk about a digital divide and whether there are computers or Internet services in inner city and rural schools.

Some imply that the students in those schools are losers because they don’t try hard, that it’s their fault, they could have fixed it. But lots of times, it’s not their fault. We are in an economy today -- five years after we hit bottom -- in which more than 20 million people do not have full-time jobs but want them. That is an economy that has failed 18 or 19 percent of the American work force. It’s not their fault. The jobs aren’t there.

You set out a kind of Marshall Plan to restore the American Dream and address the economy. What are the one or two most important things to do now?

We need a far stronger recovery and millions more jobs. But recovery in itself will not solve the problem of economic inequality in America. Economic inequality has gotten worse over the past four years -- during recovery -- than it was at the bottom.

Corporate profits went up 20.1 percent a year for the past four years in a row, and median household income went up only 1.4 percent a year in the same period. So the corporations are making money but they are not sharing it with the average employee.

We’ve got to recover to generate the jobs to put people to work. But we’ve got to do more than recover.

To do that, the single most important thing now is generating solid, high wage jobs. How do you get those jobs? There are two big things we could do in terms of policy. One, we could invest in modernizing the ports, the airports, the bridges, the railroads and the highways in this country. We are way behind countries like China in terms of how modern our seaports, airports and our rail systems are. We are way behind them. We could put people to work if we invested in modernizing our transportation system, and we would be more globally competitive as a nation. We could do that with five, six trillion dollars of investment, some public but mostly private, over the next decade and it would immediately generate some jobs and benefit the whole country. Some people say that would put us in debt, but if you generate jobs and generate growth, that’s how you pay off debt. You don’t pay off debt by tightening down and doing nothing.

A second thing we could do is level the playing field on corporate taxes. Corporations that make profits overseas pay lower tax rates than companies who do all their production in America. That’s senseless. That is cutting the heart out of our own economy. We should level the rates - in fact, probably give a lower rate to companies that operate inside the U.S. generating jobs for us at home.

Third, we should invest in manufacturing in this country. Germany has more than 20 percent of its work force in manufacturing and Germany is doing a much better job competing globally than we are. We have a huge export deficit, and they have a large surplus, and yet they pay their middle class workers more than we do. So there’s something wrong with the philosophy we’ve been sold -- that the middle class can’t be paid more. Pay the middle class more, then they’ll have more money. And it’s their spending, it’s consumer demand, that drives American economic growth.

We need to understand the economics that worked for America in the forties, fifties, sixties and seventies, and put that back to work now. We’ve been cutting back. We’ve been running an economy to benefit the big banks, the financial elite, and the multi-national corporations, and they are chewing up America. We’ve got to change that and make our economy work better for the middle of America. Those are policy decisions.

That leads me to the most important thing we have to do. We in the middle class have got to organize. We have to get out in the streets and demonstrate the way we did before - for civil rights, women’s rights, consumer rights, the environmental movement, and the labor movement.

Americans have gotten soft. They say “it’s up to Washington to do it.” Sorry. Change is not going to come from Washington. We the People have to change the power equation in Washington. We have to make Washington change. Average people have to stay engaged between elections. Yes, vote, but not just vote. My book ends with these six words: “We the People must take action.”

We have to change our mindset. We’re counting on someone else to do it or complaining that the lobbyists in Washington have too much power. Instead of that, we have to go out and change the policies and get the kind of policymakers that will help the middle class. And by the way, if the middle class does better, the country will do better because there’s all kinds of economic evidence that the high inequality of income we have now is bad for growth, and not just bad for people in the middle -but bad for the whole country.

We need to change direction.

Thank you for your comments and for your thoughtful analysis of vexing problems today -- and how they got that way.