America Owes a Debt to the National Debt

Debt played an essential role in solidifying American independence. Yet during the recent public debate on raising the debt ceiling, little consideration was paid to how we came to have a national debt in the first place, and the disastrous results of the single time the United States actually eliminated it.

In 1790, during George Washington’s first term, Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton successfully proposed turning America’s various Revolutionary War obligations into a single national debt. The debt bound the nation together; foreign creditors saw national credibility in the federal government taking responsibility for state debt. Ironically, Washington, D.C., the center of our recent crisis, was the product of the compromise that got southern states to agree to Hamilton’s plan for a national debt. The nation’s need for capital made the nation’s capital, and a floundering independent country remained independent in part because it owed money.

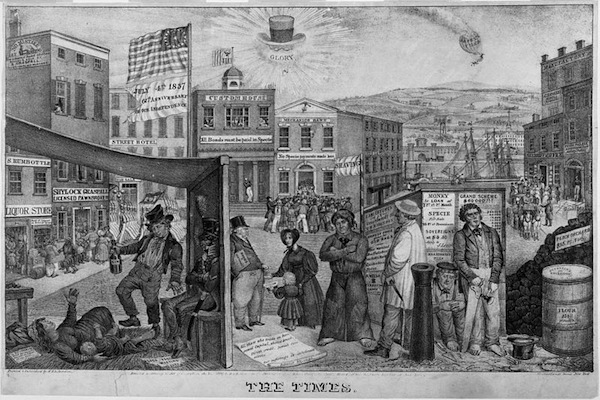

While the creation of the national debt in the 1790s helped to create the nation, the elimination of the national debt in the 1830s contributed to an epic crisis. In 1835, President Andrew Jackson, who expressed no love for centralized power but certainly didn’t mind wielding it, oversaw the elimination of the national debt. For the first and only time in its history, the federal government had more money than it owed.

On the surface, this might seem to be a moment of American triumph, but the funds used to pay off the debt derived from the sale of confiscated Native American lands and tariffs linked to slavery. The morality of the debt payments aside, Congress promised the excess funds to the states, which promptly promised the money to build canals, railroads, and banks. Meanwhile, federal funds accrued in state banks.

All seemed to be working fine until a transatlantic financial crisis known as the Panic of 1837 destroyed investors’ confidence in financial instruments and institutions. After several months of panic in the spring of 1837, banks suspended payment of gold and silver coin. This meant that the treasury department lost access to the federal government’s funds.

President Martin Van Buren, Jackson’s successor, was forced to call a special session of Congress in an attempt to end the federal financial crisis. Just like in our own times, intense partisanship reigned in Washington, and while the nation’s elected representatives debated solutions, the nation’s revenue streams began to dry up. The federal government soon acquired new debt.

More importantly, most of the federal funds that had been promised to the states never arrived. Nine states defaulted on their loans outright by the early 1840s, tarnishing America’s international reputation. Even more states teetered on the edge of default. The payment of the national debt ended in new debt, default, and hard times.

In the recent partisan standoff that led to a sixteen-day shutdown of the federal government, the national debt saved the day. Sympathy for veterans unable to receive medical care, needy children left without Head Start, vacationers stranded at Yellowstone, Antarctic researchers kept from their climate data, or furloughed government employees did not force a vote; the national debt did. The night before the U.S. reached its debt limit, the majority of our lawmakers recognized the global financial catastrophe that could result from a federal default. The reopening of the government was a direct result of the power of the national debt to force America’s elected representatives to compromise.

Americans owe a frequently unacknowledged debt to the national debt. The United States was built on it, and the attempt to eliminate it in the 1830s ended in disaster. Before we try to eliminate it the next time around, we ought to consider its history.