Acclaimed Author and Editor Victor S. Navasky on the Enduring Power of Political Cartoons (Interview)

Through modern history, political cartoonists and caricaturists have been threatened, censored, jailed, and even murdered because of their often underappreciated but unusually potent art.

Acclaimed writer and editor Prof. Victor S. Navasky examines the elusive power of political cartoons and includes rich array of notable examples in his book

The Art of Controversy: Political Cartoons and Their Enduring Power (Knopf). In this wide-ranging study, Prof. Navasky ponders with wit and thoughtfulness the unique effect of this art form that has provoked reactions from amusement to outrage and to violence.

In the book, Prof. Navasky examines the work of his friends and colleagues such as David Levine and Ed Sorel, as well as renowned artists such as Goya, Daumier, Nast, Kollwitz, Grosz, Low, Mauldin, Herblock, Steadman, and many others. The book reveals how cartoons and caricatures have worked to expose lies and stupidity—and to dictate the public discourse for good and for ill.

Readers have praised The Art of Controversy for its expansive, instructive and engaging approach to the history of political cartoons. For example, renowned novelist E.L. Doctorow commented: “As Victor Navasky, a word man, investigates the wordless art of the political cartoon—what, he asks, accounts for its implosive power?—we find ourselves in the hands of a writer of indefatigable curiosity and are caught up in the tempestuous history of newsprint art.” And activist and former presidential candidate Ralph Nader wrote: "Victor Navasky pulls it off. He showcases the significance and power of political cartoons without taking the 'funny' out of them or cloistering the amazing rage they evoke that is far beyond the power of mere words to explain."

Victor S. Navasky is the George Delacorte Professor of Magazine Journalism at the Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism, where he directs the Delacorte Center of Magazines and chairs the Columbia Journalism Review. He also is the longtime former editor and publisher of The Nation, America’s oldest weekly and, before that, he was an editor for The New York Times Magazine. In the 1960’s he was founding editor and publisher of the satirical magazine Monocle. His other books include Kennedy Justice; Naming Names, which won a National Book Award; and A Matter of Opinion, a memoir, which won the 2005 George Polk Book Award and the 2006 Ann M. Sperber Prize.

Prof. Navasky recently discussed The Art of Controversy and the unappreciated art of political cartooning by telephone from New York City.

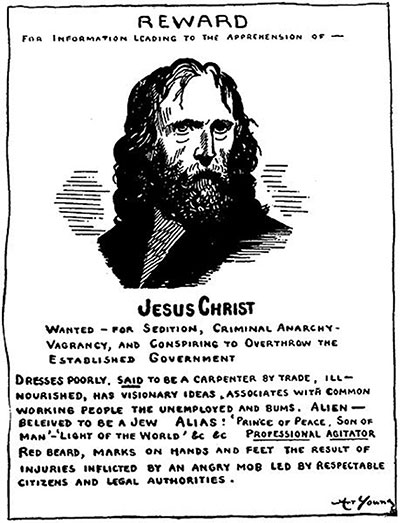

by Art Young

Robin Lindley: How did you come to write your book on the history and power of political cartoons?

Prof. Victor Navasky: I came to write it because, in more than 30 years at The Nation—first as the editor-in-chief and then as publisher—only once did my staff march on my office and demand that we not publish something in advance: David Levine’s caricature of Henry Kissinger. It shows Kissinger screwing the world in the form of a woman with a globe where her head should be with Kissinger on top and the world-woman on the bottom.

by David Levine

At the time, I called a meeting. The objection to the cartoon was that it was politically incorrect because it had to do with the sexual act showing the male on top, the female on bottom. I thought this was another example of the left’s obsession with political correctness.

The obvious didn’t occur to me until about ten years later with the Danish Mohammed [cartoons]. The Muslim world reacted violently to the cartoons of Mohammed. Everyone talked about it as a phenomenon of Muslimism and its forbidding reproduction [of images of Mohammed]. But it made me think back to when the staff marched on my office. I asked myself why was it, in this bastion of word people who object to many things, the only time they took physical action was over a cartoon?

I then started some research of my own, and of course discovered they threw Daumier into prison, and the most powerful cartoonists were the ones who caused the greatest emotional reactions, which is not unexpected. That’s how I got involved in this project.

The Levine cartoon of Kissinger came to The Nation because I had known David years before when I published Monocle [in the early 1960s] before David had his national reputation through his caricatures for The New York Review of Books and other work. He called me one day and asked if we’d be interested in the Kissinger caricature because he had done it originally for the New York Review, and he said it was too strong for them. He said, “It shows Kissinger screwing the world with Kissinger on top, the world on bottom.” I said, “Of course I’m interested but it will get me in a lot of trouble.” He asked why. I said, “I don’t know, but it will.”

Robin Lindley: And you published the cartoon despite staff objections.

Prof. Victor Navasky: We certainly published it, and we got a fair amount of mail on it. All of the cartoonists supported our running it. The staff signed a group letter on why they objected to it. Some of the mail agreed with the staff, but not the cartoonists.

Robin Lindley: From the history you relate in your book, it’s striking that time and again, in the past five centuries or so, political cartoonists have faced persecution for their images. It’s a stunning story.

Prof. Victor Navasky: It’s not just persecution. Artists and writers who were dissenters have been persecuted over time.

The leading Palestinian cartoonist Naji al-Ali was murdered on the streets of London [in 1987]. They never solved the crime, but there were two theories. One was that the Mossad did it because his cartoons against Israel were so powerful. The other was that Arafat commissioned it because he also took out after Arafat. The point is that there was no disagreement that the reason he was killed was because of his cartoons. He was coming out of the office of his magazine when he was shot. Others from the Middle East had their fingers mauled.

So over time, the reaction to these cartoons is both from government and also [from those who were] emotionally violent upset.

Robin Lindley: The violence may surprise some readers. You write that, in response to the Danish cartoons of Mohammed, more than 100 were killed in protests around the world.

Prof. Victor Navasky: Yes, and it goes all the way back in time and comes right up to the present. I cite the literature in neuroscience and social psychology to see if the neuroscientists and social psychologists can help explain this reaction.

I found some experiments in this literature, but for me they were inconclusive. For example, experiments show rats that are punished when rectangles come into their world and rewarded when squares come into their world act negatively to the rectangle. But the more elongated the rectangle, the more upset they are in their reaction to it. Neuroscientists argue that this is the equivalent of caricature, which exaggerates certain features.

Some neuroscientists found the same phenomenon in an experiment with herring gull chicks that get fed by pecking their mother’s long beak. They introduced into the herring gull chicks’ world a stick modeled on the mother’s beak, and the longer the stick, the more avidly the chicks would peck. They [the researchers] argued from that, again, that this was a caricature that exaggerated the certain features, which may apply to faces.

To me, there may be something there that is suggestive for longer-range studies of why people get so upset by caricatures, but I found the explanation more suggestive than persuasive.

My own working hypothesis is that one of the reasons people get so upset by cartoons and caricatures—especially the victims or people who identify with the victims—is that a) they are by definition unfair because they exaggerate weakness or foibles, but b), and more importantly, they’re not only unfair, but there’s no way to respond to them.

If you don’t like an editorial in The Nation or a daily newspaper, you can always write a letter, even if it’s only in your head, because you know what they’ve done wrong. If you don’t like the way you or someone you identify with is portrayed in a caricature, there’s no such thing as a cartoon to the editor, unless you happen to be a cartoonist. This is terribly frustrating and causes a feeling of impotence and I think that’s part of it. To add to that is the lingering suspicion that maybe the cartoonist, unfair though he or she may be, has gotten to the real you: the ugly truth about yourself under the cosmeticized picture of yourself you put out to the world.

Robin Lindley: You include a quote to the effect that the caricaturist searches for deformity rather than a realistic portrait.

Prof. Victor Navasky: The art critic Ernst Gombrich said that “the perfect art is the perfect form, but the perfect caricature is the perfect deformity.”

Robin Lindley: You describe political cartoons and caricatures as “second-class citizens in the world of words.” But their power, as you posit, is undeniable. French King Louis Philippe [in the 1830s] felt threatened by the cartoons of Honore Daumier and others who drew him, and he saw words as opinion but caricatures as “acts of violence,” and he ended up censoring caricatures—but not print articles.

Prof. Victor Navasky: Yes. He saw something and he not only put Daumier in prison but his publisher, [Charles] Philipon, was prosecuted many times. The king became known as “La Poire” because he was portrayed in the shape of a pear. At his own trial, Philipon introduced four pictures. One was the king and the fourth was a pear, and each one successively got closer and closer to the pear image. He said, “What are you putting me in prison for? Because I drew a pear or are you putting me in prison for the third one or the fourth one? Can I help it if the king happens to be shaped like a pear.” He made the good literal point by stressing the peculiarity and illogic of the punishment.

Robin Lindley: You also note that caricatures were especially powerful many people were illiterate, but could understand cartoons and caricatures. An anthropologist said that Martin Luther in the sixteenth century may be the father of political cartooning because he commissioned artists to draw fiercely anti-Catholic images. You include in your book a reproduction of one 1545 drawing by Lucas Cranach the Elder entitled “The Birth and Origin of the Pope” that depicts Satan excreting the Pontiff.

Prof. Victor Navasky: Absolutely. Before there was general literacy, cartoons and pictures were one of the ways people got information.

And jump ahead to the age of literacy. In Nazi Germany a publication called Der Sturmer would run vicious anti-Semitic caricatures of the Jew every week. They were not just on the cover of the magazine but they would be displayed publically as posters.

The image of the Jew in Germany, one could argue, was set by Der Sturmer itself. It’s telling to me that, in the trials of Nazi enemies at Nuremberg, the defendants received sentences of a few months, a few years, and life and execution. And the only non-military leader who I could find that was sentenced to death was the publisher of Der Sturmer. I think those who sentenced him had a general understanding of the power of these caricatures.

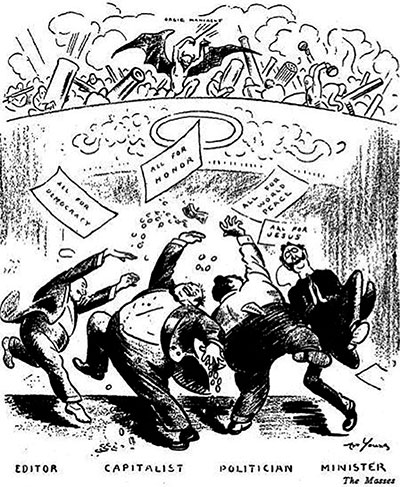

by Art Young

Robin Lindley: Don’t those images register with readers and trigger a response much more quickly than a printed story?

Prof. Victor Navasky: Yes. The Old Testament forbids graven images. And in the book I provide three theories of what’s going on: content, image and neuroscience. Content is the political message or rational aspect of the cartoon. Of greater importance is the image or “the cartoon as totem.” There’s a whole new visual culture movement elaborating on that. W. J. T. Mitchell at the University of Chicago is a guru in that movement, and he talks about how we patronize primitive peoples who believe pictures are alive. He argues that, in some sense, they are alive, and that’s why people find them so threatening. In the past, he argues, we would say these primitive people were guilty of idolatry or fetishism or animism or totemism, but maybe they know something we don’t know.

When I began to look at these images and how governments have feared them, it occurred to me that maybe the so-called primitive people are onto something. The Masses, a magazine published at the time of World War I, published the drawings of Art Young, and they were put out of business under the Espionage Act. He and other cartoonists ran things like a wanted poster that said “Jesus Christ: Wanted for Sedition” and said he was a carpenter with his picture. They [publishers of The Masses] were accused of undermining the war effort, and they were against the war.

I had seen the cartoons of the great Art Young over the years, but I had never seen the actual Masses magazine. I went to the Cartoon Library at Ohio State University where they have all of the back issues of The Masses and I saw them for the first time. It was so powerful to look at that magazine because it seemed the words illustrated the pictures. The cartoons and caricatures were so dominant that they told a story of their own.

Robin Lindley: Do you think any political cartoons actually affected the course of history?

Prof. Victor Navasky: It is hard to say, but different people’s consciousness is affected in different ways.

The great British cartoonist Ralph Steadman saw me, and he said that the great caricatures, at there best, are things that you can’t put into words. If you look at his Nixon, you understand. But if you can’t put them into words, you can’t make a logical argument about which cartoons affected the course of history.

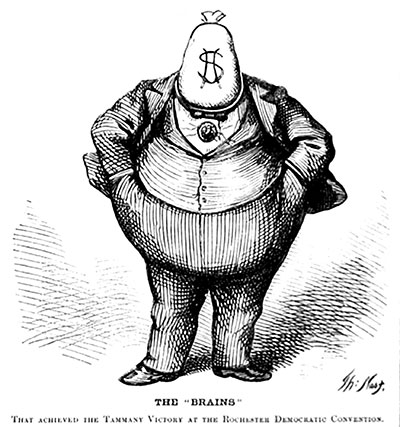

by Thomas Nast

But if you can’t put the cartoons into words, it’s hard to say which caused what historically.

Even as I talked about the book, I became self-conscious that I was using words, as we are now, to describe something that, as Steadman says, “words can’t capture.” We’re dealing in a world of symbols and paradoxes.

Robin Lindley: You discuss the work of great artists who people may not think of as cartoonists such as Goya, Picasso and Kathe Kollwitz. Speaking of Kollwitz, one of my favorites, it seems that there weren’t many female political cartoonists in the history you cover.

Prof. Victor Navasky: I attended an editorial cartoonists convention in Salt Lake City and, at this convention, a female cartoonist thought that I didn’t treat that subject with sufficient seriousness. She believed—and I don’t disagree with her—that women are discriminated against as cartoonists in the same way they are discriminated against in our culture so they haven’t been generally employed. And I go from that to think that not many women have sought being cartoonists because they didn’t see a career path there. But there are some marvelous women cartoonists.

When someone from my generation thinks of a cartoonists, I think if Herblock. And he had a role in bringing down Richard Nixon. He didn’t do it all by himself, but he set the image of Richard Nixon [in the early fifties], which was so consistent with what later happened to him that it had credibility. There’s a great cartoon he made in 1954 where a group of supporters are waiting for Nixon and someone says “Here he comes now,” and you see Nixon emerging out of the sewer from underground. That said it all. And [Herblock depicted Joe] McCarthy with his tar brush. Great cartoonists, male or female, have that ability.

Robin Lindley: You also note that David Levine called Bill Mauldin, the creator of the GI characters Willie and Joe in World War II, a great antiwar artist. Can you talk about Mauldin’s art?

Prof. Victor Navasky: Willie and Joe are these figures who are easy to identify with. They are what every GI Joe [experienced] and got to the quick and the heart of the war. And Mauldin combined that gift with his own radical political sensibility to great advantage. And not just politically, because he inspired a generation of comic strip people to do the same. I see him in the tradition of Art Young, although their styles are quite different.

I put in the book one of my favorite Art Young cartoons. It shows two children, and one is saying, “Gee Annie, look at the stars, thick as bedbugs.” It shows these poor kids and it’s a comment on poverty.

Robin Lindley: You have a background as a satirist with your satirical periodical Monocle from the 1960s. It must have been a privilege to work with the likes of artists David Levine and Ed Sorel in their early days. And it must have been quite a journey for you to do this book now on visual humor.

Prof. Victor Navasky: It has been. Among the cartoonists and caricaturists we used at Monocle, none of them were well known at the time. And now people like David Levine, Ed Sorel and Robert Grossman [are well known], and if you don’t know who they are, you would nevertheless recognize their art.

In 1978, I came to The Nation, America’s oldest weekly. It has survived with its tiny circulation whereas magazines like the Saturday Evening Post, Look, Life, Colliers, have gone under with circulation in the millions. One of the reasons The Nation survived was its low production costs and it was run by people who cared more about what it said than about making money from it, but nevertheless, they ran it like a business. One of the business insights was producing it on cheap paper.

When I first got to The Nation I met with the great designer and artist Milton Glaser and invited him to re-design the magazine in a way that would take advantage of all these pen and ink cartoonists and caricaturists whom I knew and who had a way of making political statements through their art. We couldn’t compete with the fancy, slick, full-colored magazines but, on the other hand, we could have a striking magazine that could make the most of people like Levine, Sorel, Grossman, Isadore Seltzer, Paul Davis and others.

Robin Lindley: Do you have some favorite political cartoon?

Prof. Victor Navasky: I don’t want to pick one over the others. Look at the book if you want to see my favorites. A lot of them are there even though other of my favorites like Ed Koren, Jules Feiffer and Gary Trudeau are missing.

Robin Lindley: And some media critics now say that political cartooning is a vanishing art. What do you think?

Prof. Victor Navasky: They say it’s a disappearing. With the advent of the online, digital world, while editorial pages in print may or may not be at the end of their run, which I don’t believe they are, you’ve never had more of an opportunity to use visual means of communication than you have now. Everyday, there seems to be a new app invented, whether for a cell phone or another device you carry in your pocket, or the computer on which you get your mail. So this is an art form that will have a new rebirth in a new incarnation.