Why Is New York City Still Celebrating Statues of Racists?

I recently was walking through New York City's Tompkins Square Park. I have been there many times during the last fifty years, when it was an anti-war and hippy outpost, when it was crack country, and when it was occupied by forces opposing gentrification in the East Village. But on this trip to a dance festival I stumble across something that really amazed me, a towering statue celebrating one of New York City's most notorious racists from the past. I must have passed the statue dozens of times before, but I until I started researching the Lincoln reelection campaign of 1864 and the "miscegenation hoax," it never registered on me.

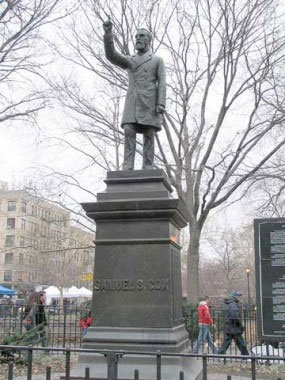

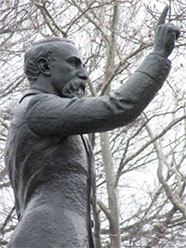

In the southwest corner of Tompkins Square Park is a statue of Congressman Samuel Sullivan Cox, "the postman's friend." The plaque on the statue credits Cox with helping postal workers secure better wages and working conditions in the 1880s and with contributing to the establishment of the United States Coast Guard. But what is left out about Cox's life and career is perhaps more important than what is mentioned. What Cox did, and what we have forgotten, tells us much about the history of racism in the United States. It also shows how charges of federal over-reach, demands for a strict interpretation of the Constitution, and the defense of state prerogatives are used to mask racist ideas and defend racist policies.

Samuel Sullivan Cox was first elected to Congress in 1856 as a Democrat from Ohio. He was defeated for reelection in the Lincoln Republican Party sweep of 1864 and relocated in New York City. Between 1868 and 1889, Cox represented Tammany Hall in Congress with time out to hold appointed government positions during Democratic Party administrations.

Cox fancied himself a champion of the United States Constitution but somehow his interpretation of the Constitution always seemed to deny rights to Blacks. On June 2, 1862, a year after the Civil War had begun but six months before the Emancipation Proclamation, Cox argued in Congress that the United States was made for white men only. "I have been taught in the history of this country that these Commonwealths and this Union were made for white men; that this Government is a Government of white men; that the men who made it never intended, by any thing they did, to place the black race on an equality with the white. The reasons for these wise precautions I have not now the time to discuss. They are climate, ethnological, economical, and social." Cox charged that Republicans and abolitionists, on the "other side" wanted to "carry out their schemes of emancipation " in an effort to "raise the blacks to an equality in every respect with the white men of this country."

Following the issuing of the Emancipation Proclamation, on January 30, 1863 Cox argued in Congressional debate against the deployment of Black soldiers by the Union army as a "humanitarian" act, fearing Black troops would be mistreated if captured and as soldiers. He was also concerned that African American soldiers would be "reduced to fiends" leading to a "San Domingo insurrection." According to Cox "Every man along the border will tell you that the Union is placed in new peril if you pursue this policy of taking the slaves from their masters to arm them in this civil strife."

During the lame duck Congress following the 1864 election that debated the 13th amendment that ended slavery in the United States, Cox continued to oppose rights for African Americans. His primary argument was that just because federal government had the authority to amend the Constitution and end slavery did not mean that it should. "Because we have the power, must we seize it? . . . If we may change the relation of blacks to whites in one respect, may we not in another? May we not change the Constitution to give them suffrage in States in spite of all State laws to the contrary? . . . Must we not declare all State laws based on their political inequality with the white race null and void? . . . If so, are we not asked to change the system, rather than to abolish slavery?"

While Cox claimed, "Speaking for myself, slavery is to me the most repugnant of all human institutions," he preferred "to leave to the States individually and of their own separate motion, the question of abolishing slavery, and the inauguration of measures to that end." 413 In the end, on January 31, 1865, Cox was one of 56 Congressional representatives who voted against the amendment to end slavery. They also included Fernando Wood of New York City and Martin Kalbfleisch of Brooklyn. 531 Seven years later, Cox was still justifying his vote claiming that "slavery was already dead by the bullet," and reunifying the nation was more important than an "abstract ceremonial of burying the dead corpse of slavery."

Perhaps Cox's most racist diatribe was a Congressional speech accusing Lincoln, abolitionists, and Republicans of promoting race mixing or miscegenation. In December 1863, a pamphlet claiming that the goal of Lincoln and the Republican Party was the "interbreeding" of "White" and African Americans began circulating. It was a Copperhead hoax perpetuated by an editor and reporter from the New York World, a pro-Democratic Party newspaper. In February 1864 Cox cited the pamphlet claiming that it proved the New York Tribune advocated "the Republican solution of our African troubles by the amalgamation of the races"; that abolitionists believed "there will be a progressive intermingling and that the nation will be benefitted by it"; and that African Americans believed "It is disgraceful to our modern civilization that we have societies for improving the breed of sheep, horses, and pigs, when the human race is left to grow up without scientific culture." For Cox, "The irrepressible conflict" was "not between slavery and freedom, but between black and white."

Samuel Sullivan Cox is only one of a number of racists from the Civil War period honored by statues, streets, and schools in New York City. There is a statue of Dr. James Marion Sims along Central Park on 103rd street and 5th avenue. Sims is honored for medical breakthroughs, but the plaque leaves out that he experimented on enslaved women without anesthetic and antiseptics. Samuel Morse is honored as an inventor with a statue near the 72nd street entrance to Central Park, but no mention is made of his nativism and support for slavery during the Civil War. There is a statue of Samuel Tilden, former governor and Presidential candidate, in Riverside Park. Tilden and Horatio Seymour, the governor at the time, promoted resistance to a federal military draft that culminated in race riots in New York City and the murder of over one hundred Blacks.

I am not calling for these statues to be taken down. A better history lesson would be placing new plaques on the statues explaining who these people really were and their contributions to the history of racism, a history that continues to plague the United States.