The Most Haunting Interview You'll Ever Read: When Japanese Islanders Were Ordered to Commit Mass Suicide

This is the text of an interview with Kinjo Shigeaki (85) about his experience as a survivor of the compulsory mass suicides which occurred on Tokashiki Island, Okinawa in late March 1945. The interview took place on April 23rd 2014. This article received 30,768 page views since its publication (as of 9/8/14). It originally was shared on Facebook by 23,000 people.

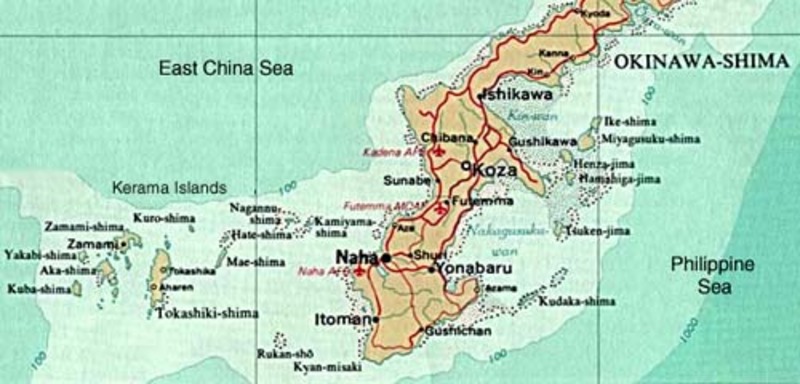

I am from the Kerama Islands, about 30 km off the coast of Naha, the capital of Okinawa. There are about 10 islands in the group.

|

Kerama Islands and Okinawa |

On the 26th March 1945 the Americans began to land on some of the islands. We lived on Tokashiki and were told by Japanese soldiers to move to Nishiyama in the north of the island, where the Japanese soldiers had their camp. We were ordered to travel after dark so the Americans wouldn’t see us. There was no shelling from the Americans that night, but it was raining heavily. I don’t know how many hours we walked, maybe four or five. We were nearly in Nishiyama when the sun rose.

About 700 or 800 people had gathered in Nishiyama. We were packed together tightly and women and children were crying. Surrounded by Japanese soldiers, we feared that something bad was about to happen. The village head was an ex-soldier himself. We waited for a long time. I don’t know how many hours passed but eventually the village head gave the order. We were to call out Banzai (Long Life!) to the emperor three times. We knew that this was what Japanese soldiers did when they were going to die on the battlefield. The village head didn’t exactly tell us to commit suicide, but by telling us to shout Banzai, we knew what was meant.

Soldiers distributed grenades among us. We were told that after you pull out the pin, you had to wait three seconds before the grenade exploded. (It didn’t seem to matter that it was prohibited at that time to distribute arms to civilians.) There weren’t enough grenades to go around because there were so many of us. Actually, my family didn’t get one. Anyway, once the grenades were given out, that was taken as a sign and the killing began immediately. The grenades were detonated, but there were few of them, so most people survived the blasts. Then people began to use clubs or scythes on each other – various things were used.

It was the father’s role to kill his own family, but my father had already died. I was only 16 years and one month old, high school age. (Although, I wasn’t in high school.) My older brother and I didn’t discuss how we would do it, but we both knew we had been ordered to kill ourselves and our family.

I don’t remember exactly how we killed our mother, maybe we tried to use rope at first, but in the end we hit her over the head with stones. I was crying as I did it and she was crying too. My younger sister would have been about to become a 4th grader in elementary school and my little brother would have been about to start 1st grade. I don’t remember exactly how we killed our little brother and sister but it wasn’t difficult because they were so small – I think we used a kind of spear. There was wailing and screaming on all sides as people were killing and being killed. If there were knives, knives were used.

After we finished, my brother and I discussed which of us would die next. Just then, a boy ran up to us. He was about 15 or 16 and he said, “Let’s fight the Americans and be killed by them, rather than dying like this.” The Americans of course had lots of weapons and we knew that we would be killed instantly if we tried to attack them. But we decided that rather than killing ourselves then and there, we would let the Americans finish us off. So, we left that place of screaming and death and set off to find the Americans.

However, the first person we met was not an American but a Japanese soldier. We were shocked and wondered why he was still alive when we had been told to kill each other. Why was it that only the locals had to commit suicide while Japanese soldiers were allowed to survive? We felt betrayed. After the war, I coined the phrase, ‘Gunsei, Minshi,’ which means ‘the army survives, the people die.’ Anyway, after seeing this soldier I was no longer willing to commit suicide.

I stayed in the mountains while the Americans bombed the island from the air. Houses, schools, post offices—all the buildings were destroyed. A fire bomb burnt down an entire village. I lived in the mountains for a couple of weeks. There was no food. I went to the beach. I couldn’t fish but I dived into the sea and got some turban shells (snails), or whatever I could find that was edible. I also found some paths made by American soldiers. Here and there they’d dropped some food cans which I was able to use. Apart from these things, there was no food. Everybody became emaciated with malnutrition. After a couple of weeks, the American soldiers were getting close to us. I observed that they didn’t shoot girls when they ran towards them. But I did see them shoot a man, a relative of my father’s – he was hit in the stomach and died where he fell. I was hiding in the grass. Finally, I was discovered by an American soldier who pointed a gun at me. I raised my hands.

I was brought by the soldiers to a truck and the truck went into the sea. At first, I thought they were going to drown us but it turned out to be some kind of amphibious vehicle. Anyway, they brought us from Aharen to Tokashiki village. There were 20 prisoners, maybe more, in that truck. At Tokashiki village we were given food. I realized that many people had survived the slaughter of Nishiyama. I later learned that some 300 people had died there that day – overall, about 600 had died in two mass suicides in the Kerama islands. It’s important to remember that such mass suicides occurred only in places where the Japanese army was present.

The POW camp where we stayed in Tokashiki was across a little track from where the Americans had their tents. Because I was young I often went to the soldiers’ camp and they would ask me, “Are you Japanese?” When I said yes they would point their guns at me but if they asked, “Are you Okinawan” and I said yes, they wouldn’t point them. I realized that they distinguished between Japanese and Okinawans.

After the war my inner struggle began. It was hard to continue living, thinking about the horrific things I’d done. I felt so terribly guilty. It was during this desperate time that a Mr Tanahara, a Christian introduced me to the Bible – Gideon’s bible. I’d never even seen, let alone read, a Bible before but flicking through it, my attention was grabbed by words like, “life” “Salvation” and “death”. I was intrigued so I got a bible myself and started reading it. It gave me comfort.

In 1948 I sailed from Tokashiki in a small traditional boat to Itoman on the Okinawan mainland to be baptized at Itoman Church. I later went to high school for a year and in 1951 entered Aoyama Gakuin University in Tokyo. I became a minister in Itoman Church in 1955 and was involved in setting up Okinawa Christian Junior College. In 1958 I went to graduate school in Manhattan to study theology.

It’s a mystery to me why I was kept alive during the war. At that time, life was treated as something insignificant. People killed each other so easily. Part of the reason we had been prepared to kill our own families was because of the nationalistic education we’d received. We were taught that Americans were not human, that they were our enemy and had to be killed.

The Japanese government should now face up to their history – their previous emphasis in education was on killing and suicide and they have never properly acknowledged that. They should admit that the Imperial army slaughtered people in China and other Asian countries. Also, they should be making efforts now to get along with China and their other neighbors, and not to cooperate only with the Americans.