How Brain Wounds and Illnesses Have Advanced Medical Science: An Interview with Acclaimed Science Writer Sam Kean on the History of Neuroscience

Modern

neuroscience evolved over the centuries as physicians learned about

the brain from horrific head injuries, vexing diseases, and

congenital abnormalities.

Modern

neuroscience evolved over the centuries as physicians learned about

the brain from horrific head injuries, vexing diseases, and

congenital abnormalities.

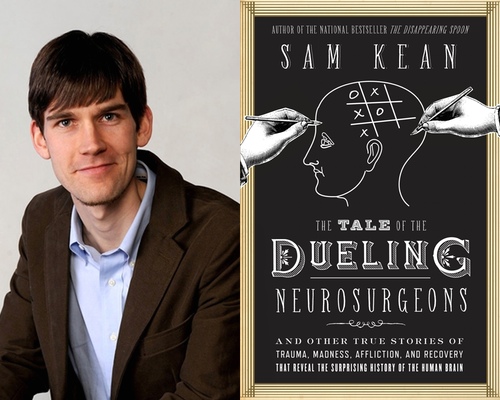

Award-winning science writer Sam Kean explores the serendipitous history of brain research in his new book The Tale of the Dueling Neurosurgeons: The History of the Human Brain as Revealed by True Stories of Trauma, Madness, and Recovery (Little, Brown and Company).

As Mr. Kean stresses, until the past few decades, neuroscientists waited for brain disasters to strike patients and then assessed how the patient’s function was affected, how damage changed the brain. His book is filled with cases of dreadful wounds, strokes, seizures, genetic anomalies, and bungled operations, as well as seemingly miraculous survivals and incredible resilience. With these compelling narratives, Mr. Kean takes readers through major structures and systems of the brain, revealing the brain’s interdependent and intricate workings.

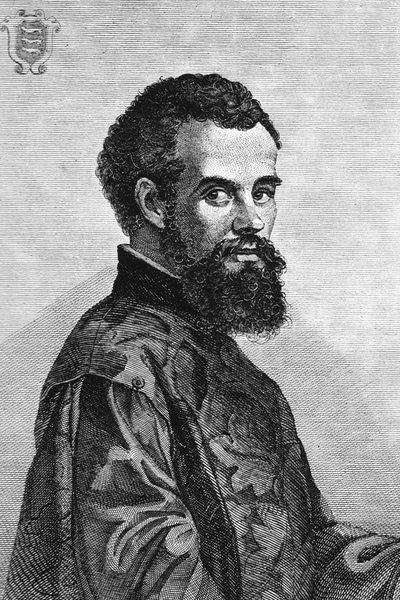

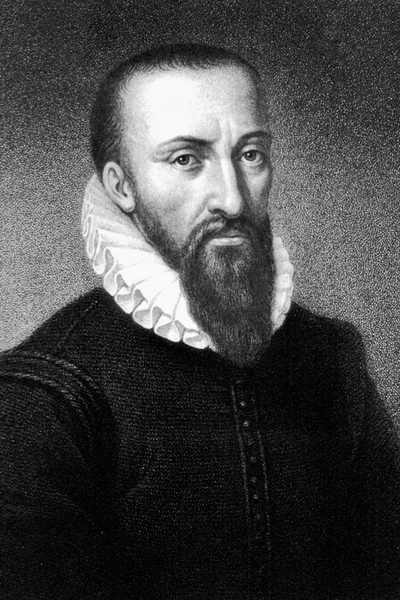

The book’s title comes from the 1559 case that brought the two most prominent physicians in Europe—Andreas Vesalius and Ambroise Pare—to the bedside of French King Henri II. The king had suffered a serious head injury in an ill-considered jousting match and, despite the efforts of these celebrated surgeons, the king expired. But the doctors emerged from this hopeless case with a new understanding of brain injury: a blow to the head may cause severe damage even when there is no gruesome external wound.

As Mr. Kean vividly demonstrates, doctors have followed in the footsteps of Vesalius and Pare to continue to learn about the brain from the plight of ill or wounded people whose struggles and resilience created the foundation of neuroscience today.

Dueling Neurosurgeons has been praised for its compulsive readability, original research, and a fresh perspective on the history of the brain. For example, a Kirkus review stated: “In tale after tale, best-selling author Kean . . . provides a fascinating, and at times gloriously gory, look at how early efforts in neurosurgery were essentially a medical guessing game.” And, from The Toronto Star: “. . .[S]cience writer Sam Kean burrows into the workings of an organ once deemed as unknowable as the far reaches of the galaxy, and does so with boyish charm, accessible language, a prodigious amount of enthusiasm and the sobering realization that throughout history a catastrophic brain injury has ghoulishly been the neuroscientists best friend.”

Mr. Kean is a science writer based in Washington, D.C. His stories have appeared in The New York Times Magazine, Mental Floss, Slate, Psychology Today, and The New Scientist, among others. His books also include The Disappearing Spoon, a history of the periodic table, which was nominated by the Royal Society as one of the top science books of 2010, and The Violinist’s Thumb, a history of the genetic code, which was a finalist for PEN’s literary science writing award.

Mr. Kean talked about his book by telephone from his office in Washington, D.C.

Robin Lindley: How did you come to write this book on the brain in history?

Sam Kean: Actually, I read a few of the stories in the book and I didn’t believe them. I thought they sounded like baloney actually. In particular, I was thinking of stories of people who suddenly lost the ability to recognize only animal or plants. That just seemed so strangely specific to me—that you could lose that ability but not anything else. I just couldn’t believe it. Also, the stories of people who lost the ability to speak but could still sing just fine. I thought there’s no way this could possibly be true. But I looked into them, and not only did I realize the stories were true, but that they provide insight on how the brain is organized, how it evolved, and how it works.

So I was thinking about these stories one day and I thought I could do a whole history of the brain based on stories like that and that would be a fun to book to write. That’s how it came about.

Robin Lindley: You also note that you had issues with a neurological problem—a form of sleep paralysis. Did that also motivate the book?

Sam Kean: Yes. That taught me that there was a lot of power in this approach. As I explain in the book, sleep paralysis is kind of the opposite of sleep walking. With sleep walking, your body is awake but your mind is asleep. In sleep paralysis, your mind is awake but your body is asleep—you can’t move your body or do anything.

I found that the cause of sleep paralysis was based on some fairly simple, basic brain chemistry. When you are dreaming, a part of your brainstem sends signals through your neurons to your spinal cord that temporarily paralyze muscles so that you’re not taking swings at dream monsters or trying to run away. It’s a benefit to be partly paralyzed in your sleep.

Sleep paralysis arises when your body forgets to turn off the spigot on these chemicals that make you paralyzed and your body remains paralyzed and you can’t move. What I found interesting was you can start with something simple like neurons and chemicals and you can jump up to some high-level processes like sleeping and dreaming.

Robin Lindley: And your problems with sleep paralysis resolved?

Sam Kean: Yes. If people experience sleep paralysis, they usually encounter it when sleeping on their backs. For me, that’s especially the case. When I’m on my back, it’s not that uncommon, so I have to make sure that I’m never on my back.

Robin Lindley: History is story—and you talk about developments in neuroscience through stories. You mention the power of story in dealing with complex scientific information. Can you talk about your use of story?

Sam Kean: Yes. I think stories are important when talking about any kind of communication, but especially when talking about science for a few reasons. One, I think that stories are the way the human brain best absorbs information. If you give people a table of fact-based numbers or if you tell them a story about what the numbers mean, they’re going to remember the story much better. That’s not to say that facts aren’t important. They are important, but the default way the human brain works is that we remember information best if presented in a story form, and it’s less intimidating for people when they learn science through character—people they can relate to who struggle with issues. Just the fact that human beings are involved makes it easier for people to get interested.

And I think stories play an especially important role in neuroscience, maybe more than any other scientific field, because when you talk about the way the brain works, you’re talking about emotion, about our interactions with loved ones, our memory, our language, our ability to express ourselves, our personality. All of these things spring from our brain. They are the stories we tell about our own lives so that, when getting into the brain, you naturally get into the elements that make up stories. There’s a natural connection between neuroscience and stories even more than in any other scientific field.

Robin Lindley: That’s illuminating too for writers on history and virtually any other field. Your book grew from unlikely stories about neuroscience. Can you talk about your research process and how the plan for the book evolved?

Sam Kean: I knew at the beginning that I wanted to give people a complete picture of how the brain worked. I wanted to include all four lobes and other structures in the brain like the limbic system. I knew I had to find stories about every single part of the brain, so that’s where my research started—figuring out what the brain does and what happens when it goes down. After that it was a matter of hunting up as many interesting stories as I possibly could. In many cases, I would find something without much digging or get a general idea of something interesting. In other cases, finding a footnote that referenced something interesting and following that footnote to other footnotes and finally finding something obscure in some paper that became something interesting to include in the book.

Robin Lindley: The book opens with the powerful story of King Henri II of France who suffered a head wound when jousting in 1559.

Sam Kean: Because he was a king, when he was injured in a jousting match, they called in the two best neurosurgeons in Europe—Andreas Vesalius and Ambroise Pare—to try to save him. They were rivals—that’s the dueling neurosurgeons aspect—but they banded together here.

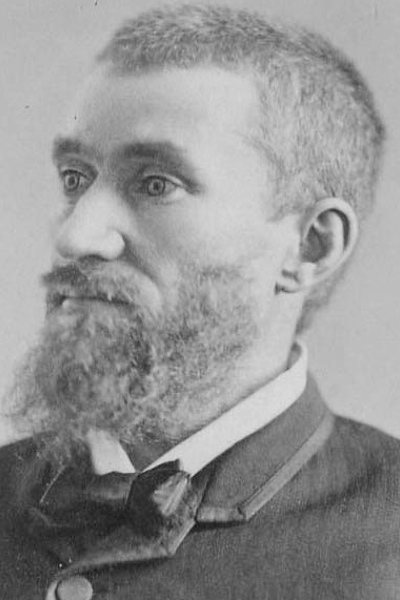

Andreas Vesalius Ambroise Pare

This story is interesting for several reasons. One, they diagnosed King Henri with a concussion, which was a controversial diagnosis then because not many people knew about them. And not many people believed in concussions because usually the outside of the skull is intact and people thought that, if the skull is okay, the brain inside must be fine. As if you have an egg and the shell is intact, then the yolk inside must be fine. But [Vesalius and Pare] reasoned that the brain was damaged.

That’s interesting because we’re still dealing with that same issue now. Four hundred and fifty years later you still hear about football and hockey players who suffer concussions but, because there’s no gory wound outside, they go back on the field. We’re still learning this historical lesson today.

The story also shows the genesis of neuroscience [with] the first significant autopsy in medical history. There were autopsies before, of course, but they were usually on criminals to punish the person. They’d be sentenced to be hanged and the body dissected afterwards.

In this case, it’s not clear why the queen permitted an autopsy on Henri’s body because it was clear what killed him and he obviously not a criminal. But it’s important that the surgeons did because they were able to check their assumptions and learn about the brain. It’s also important because what happened to the king set the standard for medical practice for other people. The king had an autopsy and that made it okay for autopsies for others, and the idea spread after that.

Robin Lindley: And this case also resonates now with thousands of troops who suffered traumatic brain injury in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Sam Kean: Again, it’s that same lesson. Just because there’s not something obviously wrong with the outside of the head people don’t get the treatment they need or other people don’t believe they have anything wrong with them because you don’t see blood or any obvious wound, although there is underlying brain damage.

Robin Lindley: It’s surprising that traumatic brain injury wasn’t studied earlier. It must have been an overwhelming issue a century ago in the massive industrialized cataclysm of World War I and in the wars since then.

Sam Kean: Wars have been critical to all of medicine, and neuroscience is a good example of that. You learn about phantom limbs from the Civil War. Injuries in the Russo-Japanese war in the early 1900s gave insight on how vision works. In World War I, soldiers were hit in the head and face, and reconstruction of the face affects one’s psychology. When you see your face in the mirror, it affects who you think you are, your sense of self.

Robin Lindley: You tell the story of Silas Mitchell who studied phantom limb syndrome—the phenomenon of feeling sensation in a limb that no longer exists—in the Civil War and after. What did he discover?

Sam Kean: Silas Weir Mitchell was an American physician working in Philadelphia during the Civil War. He did some of the first extensive clinical studies on phantom limbs. Before that, we knew about phantom limbs. There are references to phantoms limbs in Moby Dick and Charles Darwin’s grandfather Erasmus Darwin investigated phantom limbs. But they were very rare because amputations were much less common before the Civil War.

The Civil War introduced a new soft-lead bullet that you could load quickly into a gun and you could fire more often. It caused many shattered bones and limbs, so you saw more people with amputation. Mitchell, because he worked in a military hospital, ended up seeing enough of these patients to do credible studies and destigmatize them. Most people who lose an arm or leg experience phantom limb of some sort, and it doesn’t mean they’re crazy or losing their minds. It’s a natural phenomenon and the outcome of how the brain and nervous system work. The brain expects this feeling from our body, and there’s nothing unusual about this effect.

Robin Lindley: I was surprised that even some people born without a limb or limbs will also experience phantom limb.

Sam Kean: That was fascinating to me too. The story I remember is about a girl who was born without forearms, so she wasn’t feeling phantoms as a memory that was stirring to life. In school, she could feel her phantom fingers, and she would do arithmetic on her phantom fingertips. That story blew my mind, but it teaches you that the brain expects to find four full limbs. That’s the default setting of the brain and that’s how it interacts with the body—even though with this girl, the brain could see she had no forearms. But that hardwired scaffold is so inbuilt and fundamental to the brain that it overrides visual information and gives the sensation of having a full limb.

Robin Lindley: Early in the book, you focus on Charles Guiteau, a mentally ill man who assassinated President James Garfield in 1881. This case signaled another development in neuroscience with the examination of Guiteau’s brain after his execution.

Sam Kean: I think that any modern observer would look back on that case and say that Guiteau was clearly was out of his mind. There was nothing sane about the man. It’s almost entertaining to read the trial transcripts when he jumped up to sing “John Brown’s Body” and gave impromptu speeches comparing himself to Cicero and Napoleon. He was selling glamour shots out of his cell.

Charles Guiteau

He was clearly insane but because of the hatred for him because he killed the president, there was no chance he would escape the death penalty. It was really the first time that the North and South were reunited since the Civil War in mourning for James Garfield. They brought in a few psychiatrists. One in particular said Guiteau was clearly insane and the fact that he said God ordered him to do this was further evidence that he had lost his mind and we could not hang him. But the jury decided to convict him and sentence him to death.

And physicians decided to examine Guiteau’s brain. On a gross level there were a few things that weren’t completely normal, but for the most part the brain appeared to be fairly normal. But when they looked at his cells, they realized something drastic had happened to his brain. Most people at the time would not have believed that because, for a person to be truly insane, you had to have some obvious sign of brain injury, [which] goes back to King Henri II where you had to see something obviously wrong. But scientists said no—we can look at the cell and see if something is wrong. Again, it’s jumping up from the level of neurons and neurotransmitters to big questions about how the brain works—with issues like insanity.

Robin Lindley: For historians, how memory works is an important issue. You include several stories about brain damage and memory. What are a few things historians should know about memory?

Sam Kean: One thing that jumps out is how malleable memories are—how they can change over time or be distorted so you need to be circumspect and careful about what you believe. Everyone knows, on some level, that people misremember things or that people sometimes get facts wrong, but I don’t think we appreciate how common that is, how memories get distorted all of the time, even as a matter of course. It’s just something that human brains do. It’s not even a lapse. People do it—maybe not consciously— perhaps because they want to save face or suppress a traumatic memory.

Especially with firsthand recollections that are long removed, you can’t say that everything a person says is totally wrong, but you have to be circumspect about those things. It’s important to realize that memory by its nature can be changed rather easily.

Robin Lindley: And your stories about how memory works are illuminating. For example, the unusual memory loss of the English musician Clive Wearing.

Sam Kean: Clive Wearing had a brain infection from the herpes virus—not the STD, but a related virus that causes cold sores. Once in a while, these viruses migrate up the nose, along the olfactory or smell nerves and into the brain. Once they’re inside the brain, they tend to wreak a lot of havoc. In Clive’s case, they destroyed his hippocampuses, the parts of the brain very involved in forming historic memory. The result was that he woke up with amnesia and, in fact, the most profound amnesia that doctors had ever seen.

Some stories that stood out for me. He’d be playing solitaire and he would turn his head and then look back at the cards and the cards would seem to have rearranged themselves on the table. Or he might blink and the color of somebody’s shirt would seem to have changed before his eyes.

His short-term memory could not last from the beginning of a blink to the end of a blink. That’s how fleeting his short-term memory was. That’s unusual because most amnesiacs retain some short-term memory. Their memories may fade very quickly in seconds or minutes, but not as quickly as Clive’s memory faded. He lost his short-term memory and his long-term memory—and that’s why doctors described him as the most profound amnesiac that they’ve ever known.

Robin Lindley: But he retained memory for writing and some other tasks.

Sam Kean: Yes, he retained a few types of memory. He retained motor memory of the ability to do physical things. The classic example is riding a bicycle. You don’t forget the ability to ride a bicycle because of motor memory. Other motor memories include the ability to write. He could still write and still play the piano because moving your hands on a piano is a motor memory. There were abilities he retained depending on which memory system in the brain was being engaged. His long-term and short-term memory were gone, but his muscle memory, a different type of memory, remained intact.

Robin Lindley: I was intrigued also by the case of KC who suffered brain trauma in a 1981 motorcycle accident. After that he could recall trivia but could not remember personal episodes in his life. Why was that?

Sam Kean: This case provided further insight into the fact that we have different memory systems within the brain. His case showed two types of memory. He retained semantic memory of names, dates, facts and those things. A way to think of semantic memory is basically the things you could look up in a reference book. But he lacked personal memory, memories like when he was excited by a birthday gift or what it felt like to be attracted to someone or to be lonely. He lost all of those memories, which were completely wiped from his mind.

This shows that we have different memory systems. One is dedicated to bare information or facts devoid of emotion and context, and the other system involves very personal things about our lives.

Robin Lindley: How did KC function after the injury?

Sam Kean: He basically lived his life in the present all of the time. One unusual thing is that, because he lost his past, he also lost his future as well. When you project yourself in the future, you think say should I take this job? How would I feel about that? Would I enjoy that or would it make me nervous or scared?

Because KC lost all of his personal memories, he lost the ability to project himself into the future. He didn’t have a past because his memory was shot and didn’t have access to his future self, so basically he ended up living his life in a permanent present tense. He didn’t suffer for this because he didn’t know what he was missing, and from day-to-day he seemed okay. But from the outside, many of us fear this and find it sad and awful. Even the fact that he wasn’t suffering seems painful to people on the outside. It’s hard to put ourselves in his mind and understand what was going on in his head, but he didn’t suffer for it.

Robin Lindley: KC’s condition seems similar to what people with Alzheimer’s or some types of dementia experience.

Sam Kean: There are some overlaps and similarities there. His reasoning ability was fine. Some people with dementia do odd things and he wasn’t doing those things. But there was a sense of him not quite being there.

Robin Lindley What did you learn about brain function to explain the unusual situations that you first thought were apocryphal such as losing the ability to speak yet retaining the ability to sing, and losing the ability to recognize animals but retaining the ability to recognize plants?

Sam Kean: People can lose the ability to speak but not sing when connections between the language nodes and the motor parts of the brain that control the mouth go down. In that case, both the language centers themselves and the mouth still work fine, but

they can't communicate with each other, and speak falters as a result. But, the brain contains numerous back alleys and alternative pathways to send information around. So if the direct connection is broken but the alternative pathway is still intact, people might still be

able to sing because the language centers can still activate the mouth by routing information through, say, the musical centers of the brain.

As for the animal recognition, we seem to have various circuits in our brain that each specialize in recognizing a certain class of things like animals, plants, faces, etc. Those circuits give us a big advantage in some sense. But those circuits can also be damaged and go

down, and when they do, the ability to recognize that entire class of things can evaporate from the mind. That seems to be what happens when people lose the ability to recognize animals, but not other classes of things.

Robin Lindley: You also consider the vexing question of consciousness. The neurosurgeon Wilder Penfield was fascinated by consciousness and he explored it by studying epilepsy, “the sacred disease,” and mapping the brain.

Sam Kean: Epilepsy is a disease that seemed very mysterious, but once researchers got a handle on it, it provided good insights on how the brain worked.

Penfield was a neurosurgeon who was interested in consciousness. Often, when he opened the brain and tried to figure out what part of the brain he needed to remove to cure a person of epilepsy, he would take a small electrode and stimulate the surface of the brain to see what happened. A person might make a noise or speak or kick, but once in a while a person would have a very strong, vivid memory, and that interested him because he was [seeking] the seat of consciousness in humans.

Wilder Penfield

In the book, I talk about cases like Dostoyevsky and what we can learn about people who suffer from epilepsy, especially those who suffer temporal lobe epilepsy, which is often associated with people seeing visions or having supernatural feelings. They might see flashes of light or hear an angelic chorus singing. Dostoyevsky saw and felt these kinds of things, and you can see that in his writing. He had characters with epilepsy or other neurological syndromes, and people experiencing world shattering moments in the way Dostoyevsky did. He’s a very typical case of temporal epilepsy.

And both Dostoyevsky and Penfield were very religious. Dostoyevsky because he was feeling these direct contacts with God and Penfield just happened to be religious by upbringing and emotional outlook on life. Penfield used his work to further his ideas about where the soul is in the brain and the spiritual aspects of his own life. Not a lot of neurosurgeons nowadays agree with the conclusions he drew, but everyone acknowledges that he did some amazing work in exploring how the brain works and figuring out certain aspects of consciousness.

Robin Lindley: And neuroscientists are still involved in mapping the brain and considering whether we have a unified brain or whether brain functions are localized.

Sam Kean: Yes. Historically, it goes back and forth between the view that the whole brain together gives rise to language and memory. Others say no, the brain is a collection of individualized, specialized organs. And that debate continues today.

Robin Lindley: It’s intriguing that many of the physicians and scientists you profile were as quirky or damaged as their patients. I had thought of Harvey Cushing as great brain surgeon and researcher, but I learned from your book that he also had an explosive temper. Did the eccentricities of the doctors also strike you?

Sam Kean: Yes. When you get into the lives of the physicians, many were flawed. If you looked into anyone’s life, you would find flaws, but with great scientists maybe we have the expectation that they were also great human beings. But there’s no necessary connection between being a great scientist and being a good person. Or, in the case of someone like Harvey Cushing, his flaws may have made him great: his temper, his ruthlessness, his obsession. Those things didn’t make him easy to get along with, but they drove him into new areas and pushed him to greatness. He was definitely willing to do things that would strike us as cold today. There were stories about illicit autopsies and other [activities] because he was so eager to get information on how the brain works.

Robin Lindley: And perhaps their interest in the brain came from the scientists’ concern about their own minds.

Sam Kean: You see that often with psychiatrists. They may have issues of their own and their interest in how the mind works may be based on that. Yes, a deep intrinsic interest in how the brain works may have pushed some into finding out more and studying how the brain works.

Robin Lindley: And that goes back to Vesalius and Pare. They were unscrupulous in seeking out cadavers to dissect.

Sam Kean: Vesalius especially was absolutely obsessed with the human body. He would steal bodies off of the scaffold and dissect them. He would keep bodies in his room for days and days and linger over the dissection. That would strike a lot of people today as a little creepy, but his obsession ended up changing the entire field of medicine. He produced a book, On the Fabric of the Human Body, one of the great works of Western civilization. It came out the same week as Nicolaus Copernicus’s book On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres—the book that proved that the earth actually revolved around the sun. Vesalius’s book revolutionized the understanding of human anatomy and Copernicus’s revolutionized our understanding of the universe.

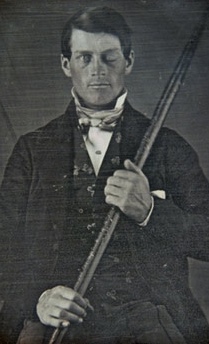

Robin Lindley: You re-tell the famous story of Phineas Gage and stress his resilience while debunking the view that he became a sort of degenerate after he suffered a severe brain injury.

Sam Kean: Phineas Gage is probably the most famous case in neuroscience and maybe the most famous case in medical history. He was a railroad worker in Vermont. A four-foot iron rod was blown through the top of his skull. The fact that he survived this injury was an absolute miracle. In fact, he walked away from the accident claiming that he never even lost consciousness, as mind blowing as it is.

Phineas Gage

He’s important because his is the first well-documented case we know of where someone suffered an injury to the brain and his personality drastically changed afterward. The problem with the case though is knowing how his personality changed. His doctor in his notes makes it clear that Gage changed in some way. Unfortunately, he’s ambiguous about what changes took place or when the changes took place. It’s not clear if he wrote immediately after the accident or if it was long-term or if it maybe got better.

Unfortunately, as the decades passed, distortions or fabrications in the Gage story crept in. Eventually, a century after the accident, you had stories circulating about Phineas Gage turning into a drunken lout or a criminal or doing dastardly things as if this wholly virtuous person had suddenly become a lunatic and an awful person.

You have to look back in the historical record to see that there’s very little evidence that such a drastic and bad transformation took place. In fact, there’s some evidence that Phineas Gage might have recovered over time. He didn’t become the Phineas Gage of old, but he might have recovered something like a normal life. Not many people know that he actually went to Chile for seven years and worked on his own as a stage coach driver. He took off for a foreign land and presumably learned a new language while he was there and dealt with customers. And he did this for seven years. This doesn’t sound like someone with severe brain damage. Again, there’s evidence that he might have gotten better, and when you look at the entirety of the Phineas Gage story it throws a new light not only on neuroscience but also on how the history of science is written.

Robin Lindley: In the Gage case, didn’t the iron bar travel into the face, through the frontal lobe, and out the top of the head?

Sam Kean: Yes, it entered right underneath the cheekbone and went behind his eye. I think the eye survived and he could see light out of it for a few days, but eventually they had to remove it. So the rod went behind his eye and then entered his brainpan and went through the frontal lobe and out the top of his skull. Like a javelin, the bar had a point on it and it flew about 25 yards and stuck back into the dirt, so it was a powerful blow to his head.

Robin Lindley: Gage and Wearing and KC and others in your book retained abilities following serious brain injuries or illness. Indeed, many of your stories reveal stunning resilience or recovery after very severe brain damage.

Sam Kean: That’s how the book grows from beginning to end. There are a lot of tales of people getting injured because that’s how neuroscience progressed and that was the only way we had of doing neuroscience for centuries. But, by the end of the book, I think there’s a sense that we were not only learning about the brain through injury, but we were learning about the brain through ways that people recover from injuries and the way the brain is able to heal itself.

Plastic changes occur where brain circuits behave differently. They may route information around damage or people may develop compensation strategies where the brain can do other things that solve the problems in a different way.

So the book grows because you see injuries but you also see how the brain changes over time. More and more scientists realize what a resilient organ the brain is. These stories on the surface seem to be of injury and woe, but if you look deep down at the person’s whole life, there are stories of persistence and courage in the way the brain helps itself.