50 Years Ago Congress Gave the President a Blank Check for War

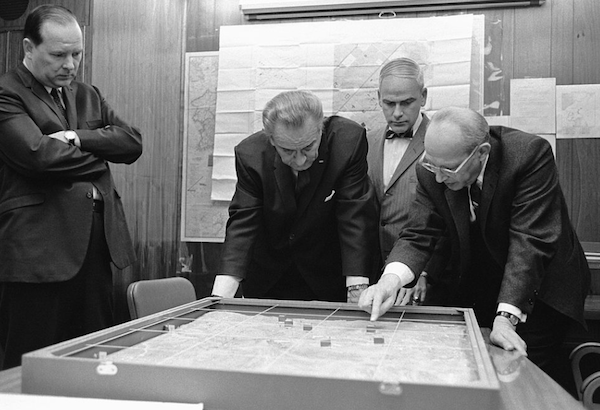

Walt Rostow showing LBJ a map of Khe Sanh in 1968

Fifty years ago, on August 10, 1964, President Lyndon Johnson signed what is known as the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. It is a day that should live in infamy.

On that day, the President gave himself the power “to take all necessary steps, including the use of armed forces,” to fight the spread of communism in Southeast Asia and assist our ally in South Vietnam “in defense of its freedom.”

Or as former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara put it decades later, it gave “complete authority to the president to take the nation to war.”

History has shown that the resolution was built on a foundation of misinformation, fabrication, and willful evasion of the truth. Contrary to what the President claimed, there was no unprovoked “act of aggression” against the American destroyers that were patrolling the Tonkin Gulf, and a second alleged incident never even took place.

But the Johnson administration was looking for a pretext to escalate the war. “We don’t know what happened,” National Security Adviser Walter W. Rostow told the president after Congress passed the resolution, “but it had the desired result.”

The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution may have had the desired result, but the war it unleashed didn’t.

By the time Lyndon Johnson left office more than four years later, we had amassed over half a million troops in Vietnam, lost nearly 37,000 soldiers, dropped more bomb tonnage than we had in all of World War II, released chemical weapons – Napalm and Agent Orange – throughout Southeast Asia, and burned thousands of South Vietnamese homes and villages to the ground.

Yet it was increasingly clear by then that we could not win the war.

Rather than stopping any dominoes from falling in Southeast Asia, the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution set in motion a series of dominoes in our own country that would profoundly alter our politics, economy, and culture for years to come.

Perhaps the most significant decision President Johnson made beyond using his newly authorized power to escalate the war was to hide the cost of the war and resist any tax increase to pay for it. Johnson feared that any congressional debate over funding the war would come at the expense of his Great Society program.

He wanted both guns and butter, but he worried that Congress would choose guns over butter. So once again he resorted to obfuscation and deception to get his way.

What resulted was a cascading series of economic consequences that would transform our nation and undermine the Great Society he so dearly wanted to protect.

To pay for the war without gutting his robust domestic agenda, Johnson resorted to deficit spending which fueled an already overheating economy that was now being asked to divert its productivity away from consumer goods and toward the war effort.

Consumer demand began to outstrip supply, and that let the inflation genie out of the bottle. Less than five years after the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution passed, inflation more than quadrupled.

Johnson couldn’t hide the rising cost of the war for long, and by 1968 he asked for a 10 percent tax surcharge on all but the poorest Americans. But it came at a cost: Congress demanded, and he had to accept, a 10 percent reduction in domestic discretionary spending. Barely three years after birthing the Great Society, he began to starve it to pay for the war. It never fully recovered.

To middle and working class Americans, the backbone of the New Deal coalition, the war’s economic impact was taking a toll. Though inflation meant pay raises once a year, prices for food and consumer goods were rising every month which then ate away at any increase in their wages.

Their standard of living began to stagnate. Nor were taxes indexed to inflation in those years, so every pay increase risked pushing them into a higher tax bracket, which took even more money from their pockets in addition to the tax surcharge they would have to pay.

These were largely Democratic voters who generally supported the president and the war – many had their own boys fighting in Vietnam – so if they were looking for blame they weren’t about to point the finger at a deceptive and misguided war policy.

Instead, they saw higher taxes, higher domestic spending, and lots of fanfare for a Great Society that didn’t seem to include them. They also saw domestic unrest and urban riots.

To them, they were hard-working Americans who played by the rules yet were now forced to tread water just to keep from falling behind while government seemed to be giving everything away to the poor. That domestic programs themselves were getting squeezed by the war was a detail that got lost in the heat of the moment.

Couple these growing resentments with the fact that it was their boys, not the children of the well-educated, who were being sent off to war. From their perspective, the liberal elites were taxing them to coddle the poor, yet when it came to defending our nation these same liberal elites sheltered their sons in colleges and universities.

Those seeking to understand the rise of Reagan Democrats and white working class Republican populists – and the corresponding demise of the New Deal majority – need look no further. The cultural and political divide that began in the Sixties was a direct result of the deceit that brought us the Vietnam War.

And what was then a still fragile liberal consensus that government could mitigate the hardships of poverty – a consensus that enabled passage of the Great Society legislation – began to erode.

That an administration could dissemble us into war would lead to another cultural and political repercussion of Vietnam: our growing and seemingly permanent distrust of government.

Trust in government peaked at 76 percent in 1964, not coincidentally the same year as the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, and declined precipitously in the years thereafter, reaching what was then a low of 25 percent in 1980, according to the University of Michigan’s National Election Studies.

Not all of this decline is due to Vietnam, but a war built on the original sin of deception, fiction, and illusion deserves a good deal of the blame.

Almost daily, Americans were treated to an official version of the war that had us winning. The Johnson administration trumpeted body counts and bombing raids and assured us, in the famous words of General William Westmoreland, that there was “light at the end of the tunnel.”

But there was no light. The dark reality we saw every night on television contradicted what our leaders were telling us. We saw bloodied soldiers, troops burning villages, body bags, fear and despair and little of the triumphalism that was emanating from the Pentagon.

When the Vietcong launched their Tet Offensive in January 1968, striking at the U.S. Embassy and other key sites in the heart of Saigon, Americans had a hard time reconciling the official version with what they were witnessing.

Thus was born the credibility gap between the American government and its citizens.

And nowhere did it grow wider than among journalists, who were greeted with untruths during the daily military briefings in Vietnam – known as the Five O’clock Follies – and saw through such euphemisms as “pacification,” which in truth meant torching Vietnamese huts and shooting those who resisted, and “collateral damage,” which in reality meant civilian deaths.

Reflexive skepticism of government remains a defining characteristic of contemporary journalism.

Watergate, which calcified the credibility gap, also grew out of Vietnam when President Richard Nixon authorized his secretive White House Plumbers to retaliate against Daniel Ellsberg, whose leak of the Pentagon Papers laid bare the duplicity behind the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution and the U.S. prosecution of the war.

Years later Senator Wayne Morse of Oregon, one of two who voted against the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, told Ellsberg that if members of Congress had seen the evidence from the Pentagon Papers in 1964, “the Tonkin Gulf Resolution would never have gotten out of committee, and if it had been brought to the floor, it would have been voted down.”

What Lyndon Johnson saw as a ploy to grant him war powers ended up harming so many and transforming our nation in ways the President surely never intended. It would end up engulfing the liberalism he so loved. The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution and the hubris behind it were the linchpins of Johnson’s Shakespearean Vietnam tragedy – and ours as well.