The Longest Battle of the First World War: Historian Paul Jankowski on the Slaughterhouse of Verdun (Interview)

Paul Jankowski, Historian (credit Mike Lovett)

On February 21, 1916, the battle of Verdun in France began with a ferocious German artillery barrage that dropped a million shells on French lines. The Germans made some initial advances but the French resisted and regained much of that territory in the ensuing months. Week after bloody week, determined leaders on both sides fed reinforcements into what an American ambulance driver later described as “the slaughterhouse of the world.”

The battle raged with horrible intensity for ten months permitting no possible advance or retreat. Hundreds of thousands of troops on both sides were sacrificed in the absurd stalemate. Later, the French celebrated the battle of Verdun as a victory and many Germans viewed it as a site of noble sacrifice.

Dr. Paul Jankowski, an expert in French history, recounts and demystifies the battle in his new book Verdun: The Longest Battle of the Great War (Oxford). Based on extensive research of French and German archival materials, Dr. Jankowski explores the military conduct of the battle as well as the experience of leaders and soldiers and the legacy of the battle for both sides. The battle of Verdun has a unique place in the memory of the war yet, as Dr. Jankowski writes, it was an indecisive bloodbath at a place of little strategic importance that resulted in no political or military gain for either side.

Dr. Jankowski’s Verdun has been praised as a significant

new political, cultural and social history of this devastating

battle. For example, historian David Stevenson wrote: "Paul

Jankowski's Verdun

is the first major study of the battle to appear in English for many

years, and the first to draw fully on archival research on both

sides. Jankowski presents a thoughtful, original, and moving account,

full of insights into the course of the fighting and its subsequent

commemoration and impact." And history professor David Hackett

Fischer called the book “a masterwork of modern literature,” and

added: “This is not only a new interpretation of a major subject.

It is also a new model of how history might be written on many

subjects."

Dr. Jankowski’s Verdun has been praised as a significant

new political, cultural and social history of this devastating

battle. For example, historian David Stevenson wrote: "Paul

Jankowski's Verdun

is the first major study of the battle to appear in English for many

years, and the first to draw fully on archival research on both

sides. Jankowski presents a thoughtful, original, and moving account,

full of insights into the course of the fighting and its subsequent

commemoration and impact." And history professor David Hackett

Fischer called the book “a masterwork of modern literature,” and

added: “This is not only a new interpretation of a major subject.

It is also a new model of how history might be written on many

subjects."

Dr. Paul Jankowski is Raymond Ginger Professor of History at Brandeis University. He teaches modern European history, specializing in the history of France. His other books include Stavisky: A Confidence Man in the Republic of Virtue and Shades of Indignation: Political Scandals in France, Past and Present. This summer he served as a consultant on a French-German documentary coproduction about the battle of Verdun.

Dr. Jankowski kindly responded in writing to a series of questions about his new book on Verdun.

Robin Lindley: How did you come to write a book on the battle of Verdun? Did it grow out of your previous work on French history?

Dr. Paul

Jankowski: The book started as a French project, and soon took

flight from there. An old French series put out by Gallimard, called

Trente Jours qui ont fait la France (30 days that made France, a

series title inspired by the phrase about 30 kings who made France).

Some famous books had been published in that series, such as George

Duby’s fine study of the battle of Bouvines in 1214, Le dimanche

de Bouvines (The Sunday of Bouvines), but by the 1980s or so the

series had somehow died. Around 2000 Gallimard decided to resurrect

it as Les Journées qui ont fait la France (The Days that Made

France), tacitly acknowledging that there might be more than 30. For

the First World War, the older series had bequeathed only two titles,

about the battle of the Marne in 1914 and the Armistice of November

1918. Both the series editor and I felt that one was needed on

Verdun.

Some famous books had been published in that series, such as George

Duby’s fine study of the battle of Bouvines in 1214, Le dimanche

de Bouvines (The Sunday of Bouvines), but by the 1980s or so the

series had somehow died. Around 2000 Gallimard decided to resurrect

it as Les Journées qui ont fait la France (The Days that Made

France), tacitly acknowledging that there might be more than 30. For

the First World War, the older series had bequeathed only two titles,

about the battle of the Marne in 1914 and the Armistice of November

1918. Both the series editor and I felt that one was needed on

Verdun.

But how, precisely, did Verdun “make” France? That question turned out to be surprisingly difficult to answer, and setting out down that path I found myself exploring much more – the origins, the character, the experience, the cultural memory of the battle, and more; I undertook to write the total history of a battle.

I had never really worked on military matters before, although the history of war, and of those of the first half of the twentieth century in particular, has always held my attention in a kind of iron grip. On the other hand, in earlier work on French history and politics, I had always in one way or another pored how imagination diverged from reality. That became a big part of the Verdun book – what happened there, and what people liked to think happened there, then and later on.

Verdun in 1916

Robin Lindley: How did the book evolve and what was your research process? I understand that you combed both French and German archives.

Dr. Paul Jankowski: If I was going to write about Verdun from so many angles I would have to use as many different sources as I could find. I used different sorts of archives: chiefly military ones, of all kinds: regimental journals providing details of a traditional sort on movements and maneuvers, postal censors who read the soldiers’ letters, records of court martials, after-action reports and casualty lists by unit, correspondence between local officers and high commands; and hundreds of published and unpublished diaries, journals, souvenirs, and letters; and newspaper accounts during the long 10-momth battle; and, afterwards, its transformation in schoolbooks, popular histories, novels, films, poems, and commemorations; and of course, the secondary narrative histories, one or two of which, like Alastair Horne’s Price of Glory are very well done.

And yes – I felt it was essential to look at both German and French sources. For too long many studies of the battles of Great War, and of the home fronts as well, concentrated on one side only. But I had a problem here. The French sources on Verdun are much more abundant than the German ones. This is partly because the battle enjoyed a more important place in French national and collective memory, but above all because of the destruction of most of the archives of the Imperial German army in an Allied bombing raid over Potsdam in 1945. (That raid spared me a great deal of work….). But I did the best I could.

Robin Lindley: Most readers now probably know little about the gruesome and futile 1916 action at Verdun that lasted for almost a year. What are some salient facts about the battle you’d like readers to know?

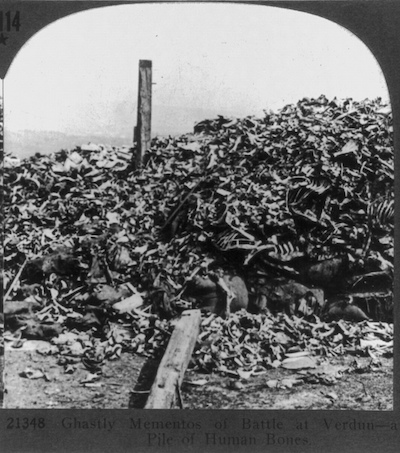

Dr. Paul Jankowski: Perhaps above all the two aspects you rightly single out. Looked at from afar, it looks singularly pointless: by the time late in 1916 the French recaptured most of the ground late in 1916 that they had lost at the beginning of the year, 300,000 French and Germans were dead. And it went on forever – continued, in fact, until the day of the armistice, even though the heaviest fighting took place during that 10-month period in 1916. Its endlessness, its macabre monotony, captures the essence of the war on the Western front, along with its seeming futility.

Robin Lindley: You demystify the battle and challenge some traditional but mistaken notions about it. What are the myths of Verdun? How do you explain the fierce German attack and the correspondingly fierce French resistance?

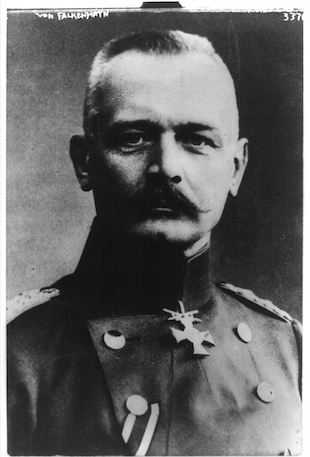

Dr. Paul Jankowski: There are many myths. One is that Falkenhayn, the Chief of the German general Staff, intended at Verdun only to bleed the French white – that attrition was his sole goal, and that he succeeded in this. Another is that the French sacrificed all to defend Verdun because of its symbolic standing. Another is that they did so because it was strategically crucial, the gateway to France. Yet another is that they fought defensively throughout, and the Germans offensively. And so on.

Erich von Falkenhayn, Chief of the German General Staff 1914-1916 (Library of Congress)

Robin Lindley: What are some surprising facts or new information that you found in your research?

Dr. Paul Jankowski: A few: perhaps my version of what Falkenhayn initially intended – to provoke counterattacks by the British and the French elsewhere on the Western front, and thereby restore a war of movement which he believed them ill-prepared to fight; my work on casualty rates, placing them in historical perspective and showing that they rose so high only because the battle lasted so long; my look at how Verdun acquired its symbolic niche in French memory, starting during the battle itself with the newspaper attempts to make sense of what was happening there, and continuing with the postwar vehicles of “memory”; and perhaps my attempt to show that French and Germans lived and experienced the battle of Verdun in the same way. Some of my study about motivation and morale might help to move us, along with the work of other historians, beyond an increasingly sterile debate about “consent" versus “constraint” as motivating factors among the troops.

Robin Lindley: Verdun was the longest battle of the First World War. You state that a major reason for this prolonged stalemate was “prestige.” What do you mean?

Dr. Paul Jankowski: I mean that its strategic significance was doubtful from the start, and that even though each side quickly persuaded itself that it could inflict as much or more damage than it suffered, prestige was the original factor that led the French to defend and then to continue defending, and prestige was the factor that dissuaded the Germans for so long for calling off their offensive and then for holding on so aggressively once they did. Once the word was mentioned, as it was in the early days, it became a self-fulfilling. There were calculations about relative rates of attrition, but these were shaky; the deeper force was national morale and national prestige.

Robin Lindley: Didn’t French politicians view Verdun as a French “Thermopylae” that could not be lost at any price?

Dr. Paul Jankowski: Yes. Initially, when the Germans attacked in February, some in the French High Command at Chantilly considered a partial withdrawal. But the President and Prime Minister wouldn’t hear of it. Then the word “Thermopylae”, used in 1792 to describe the nearby passes of the Argonne as the Prussians invaded, was used again, in the press and elsewhere. It stuck, because it captured the image of a handful of defenders holding a pass against the alien armies of an imperial foe. It turned up again in postwar accounts, in children’s books for example.

Robin Lindley: What’s your assessment of the French and the German strategy at Verdun?

Dr. Paul Jankowski: In abstract terms you could argue that the Germans should never have attacked in the way they did – hoping to rely on the advantage in heavy artillery to inflict heavy losses while suffering lightly themselves. But this war, industrial war, was new. A harsher criticism, which I believe would be justified, is that Falkenhayn attacked without any very clear strategic objective, only with vague scenarios in mind. As for the French, Petain’s defensive prudence was what the situation called for, but some of the French counterattacks, like that on Fort Douaumont in May and on Fleury in June, were ill conceived and poorly prepared. On the other hand, their offensives in the fall, when they retook the Fort and other points they had lost in February, showed a grasp of the new techniques of “methodical battle.” They were learning.

Robin Lindley: What’s your general sense of the leadership at Verdun of French General Joseph Joffre and of German General Erich von Falkenhayn?

Dr. Paul Jankowski: For Falkenhayn I would temper my criticism above with the remark that unlike Hindenburg and Ludendorff, the generals at that time in the east but who would succeed him in August, he had a sense of limits, of the predicament in which Germany found herself, and wanted to find a way to negotiate peace on the west from a position of strength before time for Germany ran out. But he should have called off the offensive sooner; this is where prestige, and a vain hope he might inflict catastrophic losses on the French, eclipsed his better judgment. As for Joffre, I am inclined to think that the criticism that he left the defenses at Verdun badly weakened before the German attack is a little unfair. He had other points on the front to worry about, and he was determined to mount the concentric allied offensives that summer on the Western and other fronts. I think some forbearance is called for. After all, in the end Verdun did hold.

Robin Lindley: You vividly portray the human face of Verdun: the terror of new industrialized warfare, the horrible conditions of the soldiers on both sides, the incredible carnage. What would you like readers to know about the lives of soldiers under fire? (It was especially haunting for me to read of their morbid fear of being physically obliterated, of being lost forever. It also seems that almost every survivor would come away with what we now call traumatic brain injury after the relentless artillery barrages.)

Dr. Paul Jankowski: I would stress the isolation and the loneliness, ironic in view of the densely packed conditions of the trenches; the sense of having left the world far behind them, a sense that both French and Germans convey, and of having entered another place where all had forgotten them; and of the pointlessness of trying to decide which battle was the most horrible or which surpassed all others in the scope and the intensity of the suffering.

I was not able to follow up on the traumatic consequences of Verdun among those who served there in the French or German ranks, but it would be very interesting to do so. Would it be possible to undertake a comparative study of postwar trauma, by battle or nation? I don’t know.

Mountain of bones assembled for internment in the ossuary that was inaugurated in 1932 (Library of Congress)

Robin Lindley: Despite the terrible conditions and futility of the battle, soldiers for the most part did not mutiny or desert at this time. How do you see their perseverance?

Dr. Paul Jankowski: In my view a number of factors at various mental levels explain their compliance. One is that in 1916 it was still possible to think they might win the war. That conviction vanished in the German army in the second half of the summer of 1918, when the army began to disintegrate. Another is that a climate of “anything is possible” fed by rumors of unrest or even revolution at home and abroad, had not set in. Such a climate would contribute to the mutinies on the French army in June 1917. At a deeper level patriotism was less a conscious set of beliefs that a part of the firmament of loyalties they lived – to their unit, but also to their family or their home, sometimes to their church, much more rarely to an ideological creed. These were almost sub-rational and inarticulate loyalties, all the stronger for it, making it very difficult if not impossible for most to reject the pressure sot belong and to conform.

Robin Lindley: How did the French and the Germans view the significance of Verdun after the First World War ended?

Dr. Paul Jankowski: I think the French came to stress martyrdom, sacrifice, and horror, the “symbolic battle of 1914-1918” as the author Maurice Genevoix, who had served there in 1915, called it, an epic that inspired the warnings of the military-minded and the indignation of the pacifists alike after the war. It has always evoked both horror and pride among many in France. I have suggested that the most common reading of Verdun is German is of noble sacrifice – of soldiers betrayed by their high command, or on the contrary sent into a pointless and even criminal enterprise. Readings like these are powerful because they become emblematic of the war as whole.

Robin Lindley: How do you feel when you walk the Verdun battlefield? I have never been there, but I sense that the Ossuary must be one of the most moving war memorials anywhere. I’ve read, visitors can actually view the shattered skeletal remains of thousands of unknown French and German soldiers?

Dr. Paul Jankowski: Yes, It’s striking, as the French historian Antoine Prost once pointed out, that Verdun should be marked not by a mausoleum, which suggests glory, but by an ossuary, which suggests suffering. The site is extensive and vast, and, like so many battlefields large and small, imposes itself by its silence. I am a member of the national committee for the Memorial of Verdun and the question of how best to keep the memory alive is a pressing one as the centenary in 1916 arrives.

Robin Lindley: Is there anything you’d like to add about the battle of Verdun or its significance for us today?

Dr. Paul Jankowski: Here’s some concluding thoughts from an essay I sent to Brandeis magazine, an in-house magazine for alums, etc., that is supposed to appear in the fall:

In the end, such transfigurations [of battles by cultural memory] reveal how a society thinks about its wars. Neither deliberate nor sinister, they spring from a natural attempt to lend meaning to events that clamor for attention and do not easily countenance the silent treatment. Sometimes, far from falsifying war, they illuminate it: the ideal of the citizen-soldier helps explain the Greek phalanx and some of the revolutionary and Napoleonic formations in the French army. Sometimes, whatever their accuracy, they eloquently proclaim a military culture: from Verdun, two absurd legends - stoic French defenders and decisive and inventive German attackers – yet distill the pithy essence of two emerging military doctrines of the interwar years. Sometimes they merely sanitize the recent past, exiling its unspeakable realities from the present. And sometimes they perform all these functions and more: at some point in the late Middle Ages chivalry, for example, probably marked the vain boast of a passing order. They are part of the history of war, a history that should encompass the construction as well as the experience of battle, never confusing the two but always attentive to their rich and reciprocal ties.