Did Mexico Reshape the American Civil Rights Movement?

It

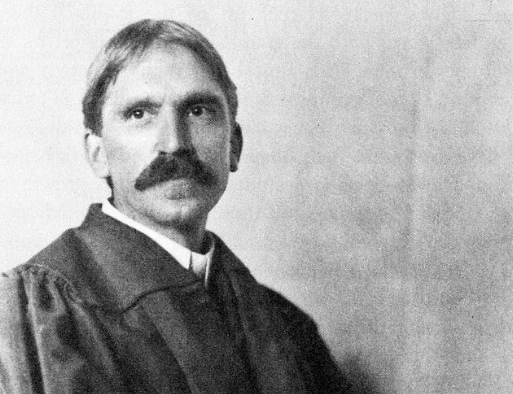

was a moment that schoolteacher Primitivo Alvarez never forgot. In

the state of Tlaxcala, 50 miles and a massive volcano to the east of

Mexico City, American philosopher John Dewey cautioned his hosts from

the Mexican federal government not to copy the institutional models

that others had constructed. It was 1926, and Dewey was surveying the

work of his Mexican students in Mexico’s rural provinces and

delivering a series of lectures in Mexico City that would shortly be

published by the New

Republic.  “Dewey wanted the rural schoolteachers of Mexico to remember the

urgency and necessity of avoiding imitation, even if the model

originated in the advanced countries, because each nation organizes

its own system of education in accordance with its unique history,

tradition, racial past, and economic and social institutions,”

wrote Alvarez. Everyone knew which models were not to be copied.

During the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz, Catholicism and social

Darwinism had been allowed to harden into an ideology of hierarchy

that younger intellectuals were now replacing. Dewey was a perfect

fit for the new institutions of postrevolutionary Mexico, Alvarez and

others believed. New ideas and new models, porous to change and

experimentation, would destroy the make-believe world of poverty and

violence that Mexico’s Porfirian leaders had created.

“Dewey wanted the rural schoolteachers of Mexico to remember the

urgency and necessity of avoiding imitation, even if the model

originated in the advanced countries, because each nation organizes

its own system of education in accordance with its unique history,

tradition, racial past, and economic and social institutions,”

wrote Alvarez. Everyone knew which models were not to be copied.

During the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz, Catholicism and social

Darwinism had been allowed to harden into an ideology of hierarchy

that younger intellectuals were now replacing. Dewey was a perfect

fit for the new institutions of postrevolutionary Mexico, Alvarez and

others believed. New ideas and new models, porous to change and

experimentation, would destroy the make-believe world of poverty and

violence that Mexico’s Porfirian leaders had created.

As he looked back on his monumental study of the New Deal, historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. celebrated the ideas of John Dewey’s pragmatism for the influence they had wrought on FDR’s politics in the aftermath of the Great Depression. “A thoroughgoing philosophy of experience, framed in the light of science and technology, could produce an organized social intelligence,” wrote Schlesinger, Jr. in The Age of Roosevelt. “And the organized social intelligence, Dewey believed, could direct the processes of social change into a rational and beatific future.” Schlesinger, Jr. was not alone in underscoring the importance of Dewey’s pragmatism in the creation of the modern liberal order. Henry May argued that pragmatism had helped usher in the bundle of ideas that separated the twentieth century from the nineteenth, a rupture that he referred to as “the end of American innocence.” Alfred Kazin had included pragmatism and social science as part of the revolution that had produced modernist literature, meanwhile. And one could see Dewey’s relationship to modern education in Lawrence Cremin’s classic studies from the 1950s and 60s.

What is surprising given Dewey’s formidable role in American culture and later historiographical return in the work of contemporary scholars like Robert Westbrook and Richard Bernstein has been the absence of attention to Dewey’s influence in Mexico at the same time that the New Deal was being formulated in the U.S. During the period of rich policy experimentation between 1920 and 1940 that followed the devastating Mexican Revolution, John Dewey’s Mexican students hitched pragmatism to state policy in Mexico in the effort to destroy the institutions of the Porfirian political order and rebuild the postrevolutionary nation anew. In newly-established public schools, they used pragmatism to integrate Mexico’s ethnic groups into a single community of citizens. In scientific institutes centered in Mexico City, they used the scientific ethos to experiment with applied psychology, anthropology, and sociology. In rural states to the west and south of Mexico City, they attempted to balance the relationship between theory and practice that Dewey believed was central to social philosophy. Just as in Henry May’s portrait of pragmatism, Dewey’s ideas in Mexico helped separate the social determinisms of 19th-century Mexico from the modernist ethics that Mexico’s revolutionaries created after 1920.

The efforts in Mexico to achieve the progressive society that Dewey once referred to as the “great community” were filled with institutional difficulty and philosophical peril. The greatest of the Mexican pragmatists, Columbia University-trained Moisés Sáenz, once chastised a group of Americans for their complacent understanding of a complex society whose civil war had just finished killing one million of its own people. “Our emotions occlude our vision; we become confused by the complexity of experience; our accomplishments contradict each other at every turn; they seem to put the most obvious and the most profound into war with one another,” he told his audience. A decade later, Sáenz created a vibrant metaphor for the attempt to blend theory with practice that John Dewey’s pragmatism had made central to modern social critique. “We are walking on the edge of a knife,” he wrote. “We must choose between excessive empiricism and excessive speculation.” Precarious government financing, ongoing local rebellions, and threats to the national territory always made pragmatist attempts at reform a difficult enterprise fraught with the possibilities of failure and slow incremental advance at most.

Yet for Americans who were trying to understand how state power could be used to alleviate economic conflict and to create new relationships among culturally distinct communities, Mexico’s postrevolutionary experiments represented a rich set of policy models that they imported into the United States as they sought to transform public government and public schools in the American West. In rural Tlaxcala in the 1930s, for example, teacher training academies provided these Americans with new ideas about how government could work with local communities to create new schools. Science institutes established by the Secretariat of Public Education in Mexico City by 1930 provided them examples of the role of social scientists in government bureaucracy. And in Morelos, laboratory schools showed them how daily work patterns could be integrated into language-instruction models.

The anthropologists, psychologists, and educational philosophers who studied Mexico’s pragmatist experiments in the 1930s carried Mexico’s lessons into the 1940s desegregation movement in Texas, California, and Arizona as they sought to refashion America’s racial hierarchy. For Ralph L. Beals, Montana Hastings, George I. Sanchez, and Edwin Embree, Mexico’s policy work represented a bridge between state-led reform efforts abroad and political change at home. Daniel T. Rodgers has argued in Atlantic Crossings that progressive policy work in Europe and the United States was never free from misunderstanding and misreading. Yet such mistranslations did not prevent Americans from learning social policy from government models abroad, he argued. In a similar fashion, Mexico’s social reform experiments became discrete policy antecedents for these American racial liberals that have not been accounted for by scholars of pragmatism, the federal state, and US-Mexico relations. Government reform and civil rights in the American West were not uniquely domestic phenomena, the career of Mexican pragmatism shows us, but offshoots of policy reform and nationalism in Mexico in the two decades that followed the Mexican Revolution. School desegregationist George I. Sanchez agreed. “Nothing has affected my thinking and my feelings more than Mexico’s experience – redemption by armed Revolution, then Peace by Revolution,” he wrote in 1966 as he looked back on his career. “This latter revolution still goes on, and I associate myself with it vicariously – from afar, and from close-up examination there as often as I can.”

Mexico’s policy influence over the United States reverses the way that scholars understand the US-Mexico relationship. We typically think of the United States as a hegemonic nation whose power shapes the nations of Latin America along a north to south trajectory. But the example of Mexico during the 1930s and 40s shows us that Mexican government policy influenced American politics as much as American power influenced the history of Mexico. Thus, while Americans tend to think of Mexico as a country of “chaos” – a word that has been perennially repeated in accounts of Mexican history from 1920 to the present day – Mexican policy change has been important to the United States in ways that Americans have not imagined. Pragmatism in Mexico helped to reshape the moral character of American nationalism and democracy, and at the level of institutional practice rather than in theory alone, during a moment of heavy social change in American history. That John Dewey’s influence was part of that process only underscores the centrality of his ideas to social change abroad as much as in the United States.