We Can't Give in to Ebola Scaremongering

Wikipedia

With all of the attention devoted to the current international Ebola outbreak, it is no surprise to see public concern that the disease might spread to the United States. It is even less surprising that some are arguing that forestalling the possible spread of this horrific disease to the United States necessitates keeping out those who are infected. The most vocal proponent of this viewpoint, Donald Trump, posted to Twitter his opinion that “People that go to far away places to help out are great-but must suffer the consequences,” and that “The U.S. cannot allow EBOLA infected people back,” in apparent reference to the evacuation of two Ebola-infected medical missionaries from Liberia to the United States for treatment.

The United States has a long history of viewing mysterious, frightening diseases as entities imported from outside the nation’s borders. The nation has an equally long history of seeking to prevent disease domestically by preventing the importation of perceived vectors of the disease, be those people or goods, from abroad. Over and over again, nineteenth-century Americans observing the epidemic spread of cholera in Europe and elsewhere sought to prevent its importation to the United States through policies such as quarantine. From typhoid to leprosy to even parasites like hookworm, there was public acceptance of the idea that these maladies had been imported to the United States via the bodies of foreigners, even when there was evidence to the contrary.

In the nineteenth century, the idea of the foreigner as a contagious danger meshed seamlessly with notion of most immigrants as being somehow biologically inferior to native-born Americans. Likewise, the idea that dread diseases spread to Americans through contact with immigrants gave credence to efforts to restrict the numbers of immigrants allowed entry into the United States, to require their medical screening on or before arrival in the country, and to compel immigrants to adopt American customs and behaviors. Viewed as biological menaces, it was not much of a stretch to decide that some, if not all, groups of immigrants were also moral menaces. The conflation of infection disease, moral panic, and isolationist policies was starkly evident a century later in the identification of AIDS with Haitians and with calls to bar HIV+ individuals from receiving visas to the United States.

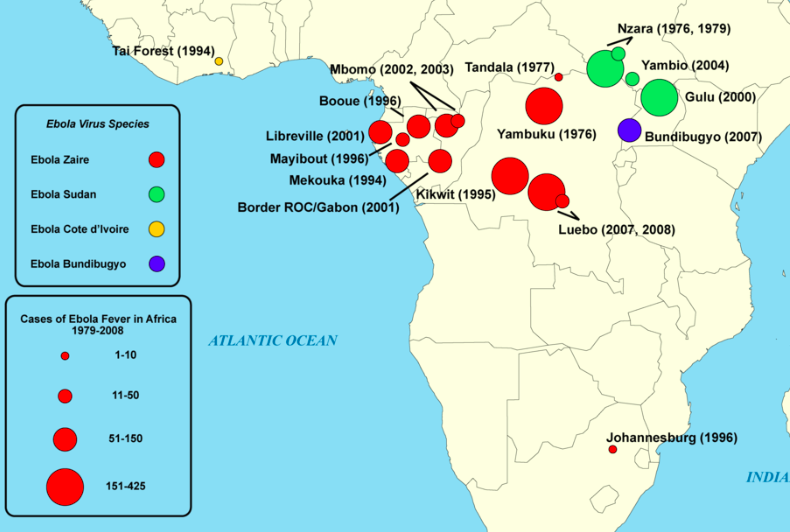

There is nothing incorrect in locating the current Ebola outbreak in West Africa, just as there is nothing wrong in understanding the Chikungunya virus as having been recently imported to the Caribbean after having previously been identified only in Africa, Asia, Europe, and the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) first occurred in Jordan and has spread through Arabian Peninsula and beyond. The majority of those in the United States who have tuberculosis were born abroad. As these examples demonstrate, diseases do travel; humans, animals, and goods can serve as vectors; and effective quarantines and screening programs can be good public health tools. But it is too easy to think that keeping the sick out of the nation will protect America’s health. Changing climate patterns, such as the warming of the American south, make it possible for insects to bring diseases like malaria and dengue to regions where the diseases had been eradicated or nonexistent. On the other hand, even if diverse disease vectors are introduced into the United States, they are not likely to spark major public health crises, given Americans’ comparatively high level of access to medical care, medicines, adequate nutrition, and potable water.

Donald Trump is merely the latest in a long line of Americans who would like to somehow protect the nation behind a virtual fence that screens out those who are seen as posing a contagious risk to the American public. While the sentiment is understandable and the public health sector does try to prevent disease importation where possible, it is important to remember our history of reading social concerns into biology. Be it Ebola, SARS, tuberculosis or any other contagious disease, let our policies be founded on science and not on conjuncture, scaremongering, or wishful thinking.