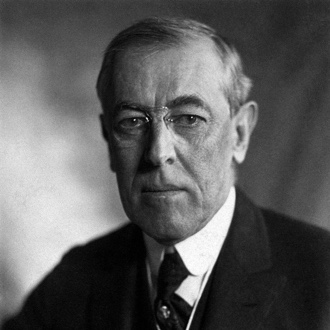

What Woodrow Wilson Did to Make "Good Government" Mean White Government

For all the recent discussions about Woodrow Wilson and racism, we are still failing to grapple fully with Wilson’s involvement in the developing racial ideology of the early twentieth century. We still begin and end our discussions with Wilson himself, missing the broader impact of his words and his presidency. It is as if we could unravel the many quandaries and paradoxes of the Progressive era by showing once and for all that Wilson was, or was not, a white supremacist. But history rarely offers such a clear-cut lesson, and we need to do more than apply labels. We must pay attention to how leaders like Wilson articulated American visions of democracy and fairness.

Woodrow

Wilson’s administration did do more than any other before or after

to institutionalize racial discrimination in the federal government.

But Wilson himself was an aloof and shadowy chief executive when it

came to personnel management, even in the area of racial

discrimination. While he strongly supported segregation, there is no

evidence that he oversaw its implementation in federal offices or

ensured consistency through a clear directive. Instead, it was the

men Wilson appointed to run his government who threaded white

supremacy into the federal bureaucracy. The resistance of African

Americans forced most of Wilson’s bureaucrats to work haltingly and

often in negotiation with each other, government workers, and even

civil rights leaders. The result was a more complex process with a

larger cast of characters. Wilson’s most remarkable role came after

the dirty work was well underway, when he blessed the marriage of

progressive politics and state-sponsored racism as necessary for good

government.

Woodrow

Wilson’s administration did do more than any other before or after

to institutionalize racial discrimination in the federal government.

But Wilson himself was an aloof and shadowy chief executive when it

came to personnel management, even in the area of racial

discrimination. While he strongly supported segregation, there is no

evidence that he oversaw its implementation in federal offices or

ensured consistency through a clear directive. Instead, it was the

men Wilson appointed to run his government who threaded white

supremacy into the federal bureaucracy. The resistance of African

Americans forced most of Wilson’s bureaucrats to work haltingly and

often in negotiation with each other, government workers, and even

civil rights leaders. The result was a more complex process with a

larger cast of characters. Wilson’s most remarkable role came after

the dirty work was well underway, when he blessed the marriage of

progressive politics and state-sponsored racism as necessary for good

government.

Thus Wilson’s role in a heartbreaking story of discrimination and derailed lives was different from the standard narrative that “Wilson segregated the federal government,” but that does not mean it didn’t matter. It mattered a great deal. Wilson was the most prominent progenitor of discriminatory and discursive practices that allowed him and other Wilsonians to claim simultaneously the mantles of progressive politics and white supremacy. Politics is made up of methods of talk as well as policy ideas, and Wilsonians narrowed issues of citizens’ rights to managerial concerns of “efficiency” versus “corruption.” They racialized efficiency (made it white), just as they racialized Republican corruption (made it black). Progressive critiques of patronage, of which Wilson was an important source as both a scholar and a politician, thus maligned black politicians—almost always identified as Republicans—as corrupt and associated racial integration with dirty politics. This process was about more than Wilson’s roots in the South or the Democratic party: it’s about how “good government” became the special preserve of white men.

One famous episode in the fight against federal segregation illustrates how Wilson’s way of talking diminished the possibilities for racial equality in America. On November 12, 1914, Wilson met with the civil rights activist William Monroe Trotter for the second time in a year to discuss his administration’s policies toward black federal employees.i Trotter visited the White House to protest the drawing of the color line across the offices and the opportunities within the federal bureaucracy. In their previous encounter, Wilson had urged Trotter, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, and the rest of their delegation to be “patient and tolerant,” but since that time, he had given African Americans little reason to be either. The result of the second meeting was a confrontation that revealed just how difficult it could be to penetrate the fundamental racism of Woodrow Wilson. More important, I argue, it would also help to set the terms on which white supremacy would be justified in national government for decades afterward.

Wilson was clearly uncomfortable with Trotter. The brilliant and demanding black leader understood Wilson far better than Wilson did him. All too aware of Wilson’s refusal to see him as an equal, Trotter nonetheless demanded to be heard. He pushed Wilson hard to live up to the principles of American democracy and the “New Freedom.” But Wilson’s response, a grumpy and patronizing reiteration of his pledge to run a just and well-managed government, revealed his inability to grasp Trotter’s forceful rights claims. The two men faced each other from different planes.

Trotter spoke first. He reminded the president that his administration had not fulfilled his promise to him and other black Democrats to deal fairly with black Americans. Trotter spoke powerfully and steadily. He elevated what Wilson saw as a question of public administration to one of American citizenship and liberty. Segregation in Washington was distinct from segregation elsewhere. If African Americans could be “segregated and thus humiliated by the national government at the national capital,” Trotter said, “the foundation of the whole fabric of their citizenship is unsettled.” Hoping to provoke his liberal sympathies, Trotter cut to the marrow of Wilson’s progressive politics: “Have you a ‘new freedom’ for white Americans and a new slavery for your Afro-American fellow citizens?” Wilson’s secretary, Joe Tumulty, later told journalist Oswald Garrison Villard that the speech “was one of the most eloquent he had ever heard.”

In his answer, Wilson’s famous patrician demeanor and didactic tone were largely absent. He sounded exasperated and tired, falling back awkwardly upon platitudes. Narrowing Trotter’s demands for equality, he imagined Trotter as merely representing one of the many interest groups within American politics that he had long found loathsome. Wrapping himself in the cloak of a morality higher than politics, Wilson played victim. He talked of the burden he felt in the White House. “God knows that any man that would seek the presidency of the United States is fool for his pains,” he moaned. “The burden is all but intolerable, and the things I have to do are just as much as a human spirit can carry.”

Trotter’s blackness unnerved Wilson. The assertive Trotter calling out the incomplete vision at the heart of the “New Freedom” was a nightmare. Though his mental state—shaken by his wife’s recent death and war in Europe—probably made his “angry black man” fantasy all the more vivid, Wilson nonetheless would never have had a way of processing Trotter’s outrage. Wilson’s meeting with Trotter revealed the way in which his “democratic universalism” applied only to white people.ii

Gathering himself, Wilson returned to his usual well-wishing talking points on “race relations,” a kind of cold speech that disclosed Wilson’s assumption that black people were something other than real Americans.iii Firm in the belief that Anglo-Saxons were the shepherds of the United States (and indeed of all humanity), he spoke as if welcoming a visiting group of foreigners. “The American people, as a whole,” he promised Trotter, “sincerely desire and wish to support, in every way they can, the advancement of the Negro race in America.” It was simply “unwise” to expect prejudices to vanish overnight, and, therefore, it would be rash not to obey the wishes of white workers. For if things moved too quickly, “friction between the white employees and the Negro employees” would be the inevitable result. “We are all practical men,” Wilson declared, invoking his manly and progressive empiricism. “We know that there is a point at which there is apt to be friction, and that is in the intercourse between the two races. . . . We must strip this thing of sentiment and look at the facts.” Federal administrators had no intention of being unjust, Wilson explained; “they have intended to remedy what they regarded as creating the possibility of friction, which they did not want ever to exist.”

Wilson’s repeated use of the word “friction” was meaningful. It was an appeal to the kind of civil service reform he had long advocated, though now merged with a racist disregard for African Americans.iv In 1887, as a young political scientist, Wilson had proposed a rational “study of administration” that sought the means to “destroy all wearing friction” in the management of government.v On both sides of the Atlantic, mechanical metaphors became standard in progressives’ discussions of institutions and bureaucracies, reflecting their hope that scientific management might bring order and harmony to the chaos of industrial capitalism.vi Friction, explained bureaucracy’s famous interrogator, Max Weber, was the enemy of efficient management.vii “Precision, speed, unambiguity, knowledge of the files, continuity, discretion, unity, strict subordination, reduction of friction and of material and personal costs,” declared Weber, “these are raised to the optimum point in the strictly bureaucratic administration.”viii Progressives clung to notions of dissolving “friction” and promoting bureaucratic efficiency as essential to government reform. Progressive columnist Walter Weyl argued that progressive government could even “regulate business as to prevent or lessen waste, internal friction, [and] inter-business friction.” To Wilson’s policy muse, Louis Brandeis, “efficiency is the hope of democracy.”ix

In the mouths of segregationists, this discourse turned white and black workers into mere “colliding interests” with segregation as the neutral solvent rather than an act of discrimination. “Race friction” as a concept erased the individuality of the people involved, even as those who talked of it varied in their sympathy for African Americans (nearly everyone in the period, black or white, used the term).xGovernment efficiency, as Weber explained, was a profoundly impersonal matter, and the mechanical metaphor necessarily dehumanized human relations, reducing racism to an inevitable function of circumstances. It had a discursive power that insisted upon, indeed naturalized, the belief that black and white people could not be expected to get along as equals. It was this ability to further a racist assumption while also promoting a progressive agenda that gave that specific word so much power for Wilsonians.xi

Facing Trotter, “friction” was thus a useful metaphor for Wilson. Eliminating friction meant rising above “collegial interests” to see administration as merely a matter of moving parts that could be made to move more smoothly. When Trotter tried to make apparent the human toll of racial discrimination, Wilson retreated to bureaucratic speak, with its comforting assurances that anything that increased efficiency was in the interest of all Americans. “Efficiency is the difference between wealth and poverty, fame and obscurity, power and weakness, health and disease, growth and death, hope and despair,” wrote one “expert” in a November 1914 issue of The Independent. “Efficiency makes kings of us all.”xii This creed was integral to Wilson’s approach to government.xiii Every Wilsonian cause—from tariff reduction to civil service management to rural credits to monetary reform—carried the virtue of efficiency. As president of the United States and an articulate spokesman for administrative reform, Wilson made a powerful case for ignoring the demands of black Americans in the service of efficient government.

Perhaps most important, Wilson’s call for smooth administration depicted Trotter as the radical activist demanding drastic change. It was Trotter, not the Wilsonians, who was trying to imagine a new kind of government management. It was African Americans, not southern Democrats, who were creating “friction” by moving too quickly to alter the terms of American citizenship. Such a formulation performed a powerful erasure: suddenly fifty years of competent and peaceful black government service had never happened. Wilson leaped from the “unwise” empowerment of slaves in the 1860s to the “unwise” equality Trotter was demanding. Whatever Wilson’s beliefs about the potential for human evolution and the possibility of uplift, black Americans were no more ready for full citizenship in 1914 than they had been after the Civil War. “Practical men” knew this, even if Trotter did not.

Trotter resented Wilson’s paternalism: “We are not here as wards. We are not here as dependents. We are not here looking for charity or help,” he informed the president. “We are here as full-fledged American citizens, vouchsafed equality of citizenship by the federal Constitution.” If Wilson wanted to talk management, Trotter had moved on to fundamental rights and equality. But the meeting was over.

The morning after the meeting, the front page of the New York Times told of Wilson’s support of segregation.xiv Speaking before his congregation of black Washingtonians on Thanksgiving Day, Reverend Francis J. Grimké thanked Trotter for revealing where Wilson stood. “The truth has at last come out,” he announced.xv

In fact, Trotter’s triumph was fleeting. A well-meaning and liberal Wilson overwhelmed by an aggressive black man would be the meeting’s lasting image.xvi Many, like Wilson, read black men demanding equality as a physical threat. Trotter and his delegation were not politicians or citizens; they were, read one supportive letter to Wilson, a “gang of negroes” whose “insulting and uncalled for manner” revealed “that the more you educate a negro the smarter he thinks he is, and the meaner he gets.”xvii

In those first years of the Wilson administration, white supremacists achieved two major victories: they vanquished the Republican patronage machine that had been so crucial for black mobility, and they established federal discrimination as a progressive reform for the whole nation. Wilson successfully connected white supremacy to the progressive and moral imperative of efficiency, and efficient administration continued to serve as a justification for discrimination by bureaucracies and by the state in general. The packaging of tales of “racial friction” in consistent rhetoric helped to embed a belief in American culture and politics that black and white Americans sharing space was necessarily a combustible circumstance—one to be avoided at almost any cost.xviii

Wilsonians’ justification of racial discrimination was critical to the changing place and power of black citizenship within the twentieth-century American state.xix Wilson always maintained that the goals of his administration were fairness and efficiency. His response to protests mattered as much as the discrimination that led to them because, as he spoke, the negotiated practice of drawing the color line became governing theory: segregation and discrimination were necessary for good, clean, and modern government.xx The issue was not one of politics or rights. The administration sought to delegitimize public objections to segregation by marking any protest by employees as both insubordinate and fallacious.xxi African Americans and some allies never accepted this argument, of course, but the vast majority of white Americans did not question it. In this way, federal discrimination, including administrators’ explanations of it, played its part in the national institutionalization of white supremacy in the United States. False meritocracies have a way of transforming socially constructed hierarchies into natural expectations.

The bureaucratic segregation and discrimination that metastasized in Wilson’s government involved a new racial system, one that just a few years later would seem timeless. Wilsonian discrimination was not simply the establishment of segregation in federal offices by one Democratic president. Rather, it constituted a dramatic change in national politics at the hands of an articulate spokesman for bureaucratic rationalization, progressive politics, and African American disfranchisement. This history illustrates how Woodrow Wilson’s progressive politics was complicit in twentieth-century racism. Contrary to the hopes of conservative commentators, this complicity should not lead us to toss out the important and meaningful reforms of the Progressive era. Rather, it should force us to recognize the complexity of our past and the too-frequent incompleteness of our democratic aspirations.

Endnotes

i The transcriptions of Trotter and Wilson’s two meetings were recovered by Arthur Link’s Papers of Woodrow Wilson Project team and published in Lunardini, “Standing Firm.”

ii Renda, Taking Haiti, 109. For Renda’s brilliant gendered reading of the Trotter/Wilson meeting, see pp. 108-15. On fundamental dissonances in Wilson’s liberalism, see Skowronek, “Reassociation”; Dorothy Ross and other students of Wilson have concluded that his particular psychological makeup encouraged him to “project his anger onto those outside the circle of his own identity.” Renda, Taking Haiti, 111; Ross, “Woodrow Wilson,” 667.

iii For an incisive history of the term “race relations,” see West, Education.

iv While historians have noted Wilson’s desire to avoid “racial friction,” their accounts have yet to fully explore the discursive work and assumptions embedded in this key word. Samuel Lonsdale Schaffer, “New South Nation,” 271-89; Ring, Problem South, 184-93. On key words in political discourse, see R. Williams, Keywords; and Rodgers, Contested Truths.

v W. Wilson, “Study of Administration,” 203.

vi “What Efficiency Means to Ten Efficient Men,” The Independent, November 30, 1914, 326-36; Mosher, Democracy and the Public Service, 70-73; Waldo, Administrative State, 186-96; Jordan, Machine-Age Ideology, 68-90; Rodgers, Atlantic Crossings, 207.

vii “Friction,” or, rather, the German word “reibungsflächen” (sources or surfaces of friction), appears throughout Weber’s famed writing on bureaucracy. Indeed, political scientist Alvin Gouldner critiqued Weber for being more concerned about “friction” than actual power relations. Gouldner, “Industrial Sociology,” 397. For an example in German, see Weber, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft, 560.

viii Weber, Economy and Society, 973-74.

ix Weyl, New Democracy, 291-92; Louis Brandeis, “Efficiency and Social Ideals,” The Independent, November 30, 1914, 327.

x In 1907, Calvin Chase noted that white racism was causing “friction” in the Census Office. The same year, Census clerk Darwin Moore hoped that he would be assigned to fieldwork in a way that would avoid “friction.” In 1910, John Dancy assured President Taft that he had performed his function as recorder of deeds “without the slightest friction.” “Call a Halt Mr. Director,” Washington Bee, March 23, 1907, 1; Darwin D. Moore to S. N. D. North, July 31, 1907, Darwin D. Moore, PF NPRC; John Dancy to William Howard Taft, February 26, 1910, file 547, reel 331, Taft Papers.

xi McAdoo to Villard, October 27, 1913; Daniels quoted in Samuel Lonsdale Schaffer, “New South Nation,” 367-68. For more on Daniels’s reforms in the Navy Department, see pp. 316-85; “Legislators Plan School Probe,” Washington Post, January 22, 1911, 1.

xii Edward Earle Purinton, “Efficiency and Life--First Paper: What Is Efficiency?,” The Independent, November 30, 1914, 321.

xiii W. Wilson, The New Freedom; Woodrow Wilson, “An Address on Tariff Reform to a Joint Session of Congress,” April 8, 1913, in Papers of Woodrow Wilson, 27:271; “Wilson at Luncheon Champions Daniels,” NYT, May 18, 1915, 5; Woodrow Wilson to William G. McAdoo, October 24, 1913, box 518, McAdoo Papers; Woodrow Wilson, “An Annual Message to Congress,” December 2, 1913, in Papers of Woodrow Wilson, 29:6; Woodrow Wilson, “Remarks upon Signing the Federal Reserve Bill,” December 23, 1913, in ibid., 65.

xiv “President Resents Negro’s Criticism,” NYT, November 13, 1914, 1; “Race Protest to Wilson: Constitution League Objects to Segregation of Negro Clerks,” NYT, October 19, 1913, 15; Fox, Guardian of Boston, 181-82.

xv Grimké, Excerpts from a Thanksgiving Sermon, 4.

xvi The Washington Evening Star chose to emphasize the offense, reporting secondhand that “the President is known to have said in effect that the spokesman’s manner was offensive beyond his previous experience in the White House.” “President Rebukes Negro Spokesman,” Washington Evening Star, November 12, 1914, 1. Julius Rosenwald, the millionaire owner of Sears, Roebuck & Co. and a financial backer of Booker T. Washington, spoke for many white liberals when he expressed his unhappiness with Trotter, whom he considered a “notoriety seeker, whose methods are dismaying to the conservative members of his race.” Julius Rosenwald to Woodrow Wilson, September 4, 1913, file 152a, reel 230; Julius Rosenwald to Woodrow Wilson, November 13, 1914, file 152a, reel 231; both in Wilson Papers. Other white respondents were less generous. In a letter to the Los Angeles Times that she forwarded on to Wilson, Mary S. Smith supported the president “for refusing to allow a committee of insolent negroes to dictate to him how he should run the office of a great country.” Claude G. Stotts to John Skelton Williams, November 13, 1914, box 126, McAdoo Papers.

xvii Claude G. Stotts to John Skelton Williams, November 13, 1914, box 126, McAdoo Papers.

xviii Historians Thomas Sugrue and David Freund have tracked assumptions and fears about racial friction among white employers and white homeowners--and the resultant exclusion of black workers and families--to industrial cities like Detroit in the middle decades of the century. Sugrue, Origins of the Urban Crisis, 93, 98; Freund, Colored Property, 176-240. There were plenty of indications of Wilson’s rhetorical success over the next few years. For example, NAACP board member Joel Spingarn advocated segregated army camps for the training of black officers during World War I because doing so would offer more opportunities for promotion of black soldiers—the same justification McAdoo had offered for separate divisions within government departments. And black soldiers at the segregated officer training camp in Des Moines, Iowa, were told by their white officer that it was up to them to keep racial peace: “It should be well known to all colored officers and men that no useful purpose is served by such acts as will cause the ‘color question’ to be raised,” read the infamous Bulletin No. 35. “Attend quietly and faithfully to your duties, and don’t go where your presence is not desired.” Tushnet, “Politics of Equality,” 891; Berg, Ticket to Freedom, 23-24; McAdoo to Villard, October 27, 1913; Bulletin No. 35 quoted in Chad L. Williams, Torchbearers, 87. The Milwaukee Free Press credited Wilson’s “endorsement of the segregation principle” for a slew of residential segregation laws in American cities, from Baltimore to St. Louis. Milwaukee Free Press, reprinted in “Wilson, ‘Father’ of Segregation,” Chicago Defender, April 22, 1916, 1; Lentz-Smith, Freedom Struggles, 33.

xix For a broader look at the way US citizenship has been contested and frequently narrowed, especially for minorities and women, see Glenn, Unequal Freedom; Smith, Civic Ideals; Canning and Rose, “Introduction: Gender, Citizenship, Subjectivity”: 427-433.

xx In this way, we might see the resistance of African Americans as “productive” in the Foucaultian sense: it created a new form of power of which it then became a victim. Pickett, “Foucault and the Politics of Resistance”: 458.

xxi James Scott’s schema of “hidden transcripts,” though perhaps overly generalized, can help us to expose the ways in which progressives’ “good” intentions, what Pierre Bourdieu calls “euphemization,” played a fundamental role in justifying discrimination and hobbling protests against it. Scott, Domination, ix-16, 49; Bourdieu, Outline of a Theory of Practice, 191.