Silver Spring, Maryland Has Whitewashed Its Past

As journalists and academics swept into American communities in turmoil over African American residents killed by police officers, James Loewen urged these visitors to question what they see. “When researching a town or county, if it is overwhelmingly monoracial, decade after decade, ask why,” Loewen wrote earlier this year. The same could be said about a place’s history: if the history omits African Americans, historians should ask why.

A pair of Ethiopian restaurants on Georgia Avenue, one of Silver Spring’s main streets.

I have written about the erasure of African American history in an Atlanta, Georgia, suburb. Ever since encountering the deliberate efforts to produce a historical and historic preservation narrative that fits Decatur’s carefully crafted municipal image, I now read history and historic preservation documents with Loewen’s questions in mind. When I returned to Silver Spring, Maryland, in 2014 after nearly four years in Georgia I revisited the histories produced about the Washington suburb and found disturbing parallels to what I was documenting in Decatur.

Silver Spring is an unincorporated place in Montgomery County adjacent to the District of Columbia’s northern boundary. Today it is a rich polyglot community with large numbers of immigrants. The community has been dubbed “Little Ethiopia” for the many restaurants and groceries that have opened there in the past 20 years. It is easy to walk through the new Veteran’s Plaza and hear conversations in Spanish, Amharic, French, and Georgian.

Yet, Silver Spring hasn’t always been such a heterogeneous place. It emerged in the first quarter of the twentieth century as a sundown suburb knit together from several dozen residential subdivisions that excluded African Americans through racially restrictive deed covenants. Once a sleepy agricultural hamlet, Silver Spring became a middle-class bedroom community for Washington bureaucrats and real estate entrepreneurs.

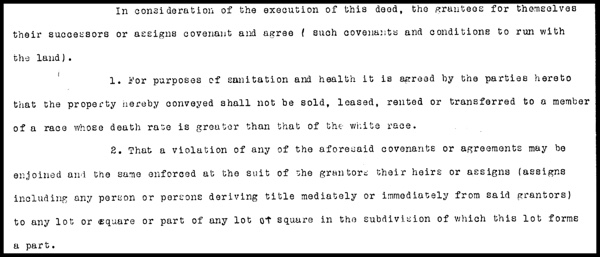

Typical Montgomery County racially restrictive deed covenant. Source: Montgomery County Land Records, Liber 342, Folio 463 (January 23, 1924).

For much of the previous century, the only African Americans who lived in Silver Spring’s core, the area within a one-mile radius of the intersection of its two main streets -- Colesville Road and Georgia Avenue – were domestic servants. African Americans could work in Silver Spring but they could not live there, worship there, go to school there, or play there. The businesses willing to take black money – there weren’t many, longtime area residents have told me – rigidly enforced Jim Crow rules: no eating in, no using the front door, and no trying on clothes or hats.

Silver Spring was a strictly segregated Southern town that vigorously resisted integration well into the 1960s. The community’s Jim Crow past is well known by the African Americans who grew up in neighboring suburban communities where African Americans weren’t excluded and in nearby Washington.

But because African Americans didn’t historically live in Silver Spring doesn’t mean they were absent from its historical landscape. They could be found in middle class homes cleaning, gardening, and raising their employers’ children. They worked in the back rooms of the stores that didn’t serve African Americans. And, they built the streets, stores, and homes that today’s historic preservation advocates celebrate.

The African American presence was an important part of Silver Spring’s history that was just as important as their absence from other parts: the schools, the tax rolls, and the growing entrepreneurial class. This was by design: Silver Spring, a place without formal boundaries, was the creation of a handful of white real estate speculators who owned the downtown businesses and who bought the large former farms turning them into subdivided tracts that sprouted bungalows and period revival cottages for thousands of middle class white residents.

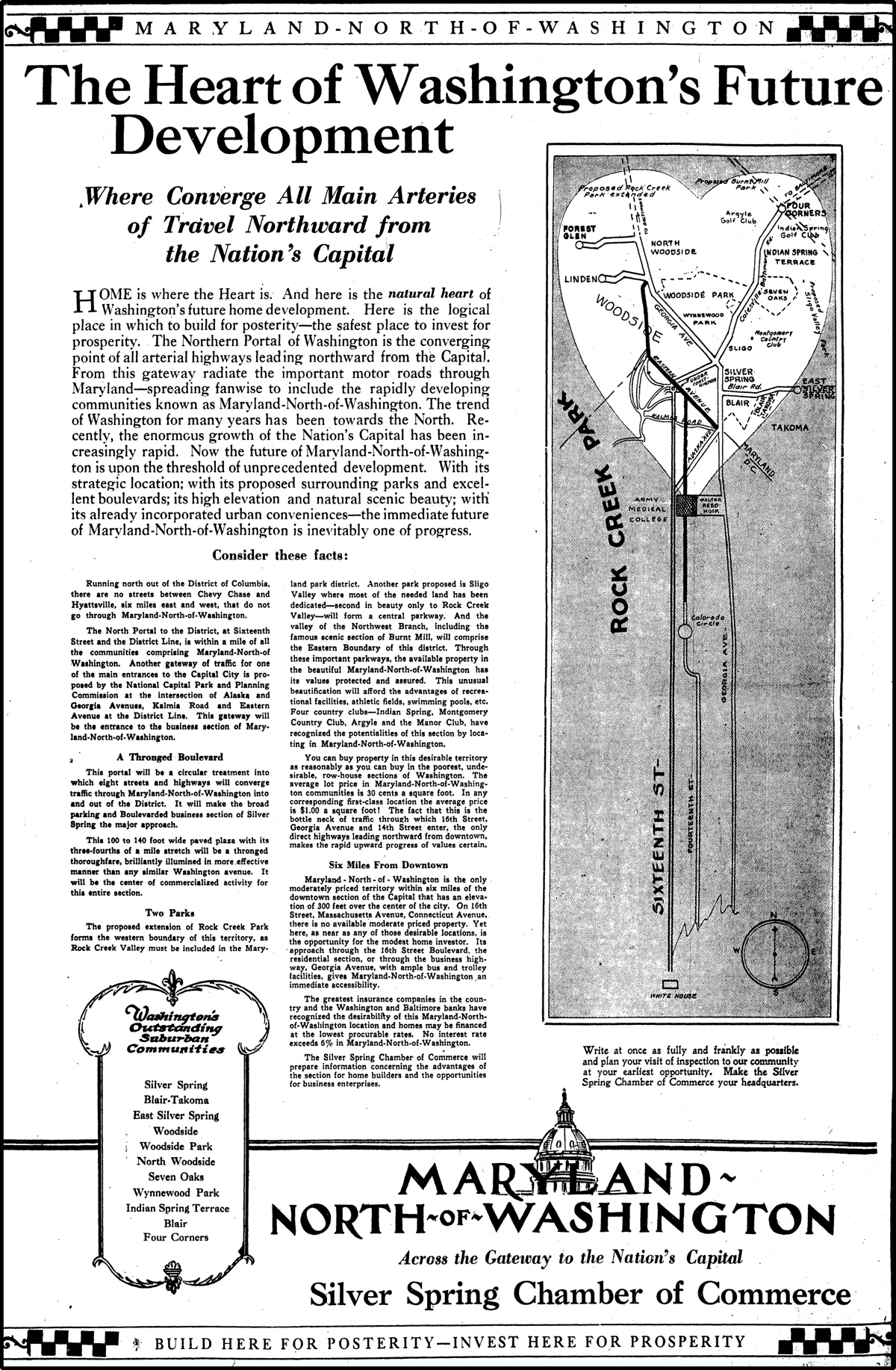

The same entrepreneurs who founded the Silver Spring Chamber of Commerce and who owned the real estate companies were the boosters behind packaging 11 communities under the marketing umbrella, “Maryland North of Washington.”

Silver Spring Chamber of Commerce advertisement published in the Washington Evening Star, September 10, 1927.

The rules in Silver Spring’s businesses were widely understood by the area’s African Americans who knew by word of mouth where they were unwelcome. The blunt racially restrictive covenants attached to more than 50 residential subdivisions between 1900 and 1948 completed the barrier to African American entry to Silver Spring society.

Key legal and legislative actions helped deconstruct the exclusions to African Americans. In 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled racially restrictive covenants unenforceable; in 1962, Montgomery County enacted an open accommodations law prohibiting discrimination by businesses located in the county; and, in 1967, Montgomery County enacted an open housing law prohibiting discrimination based on race.

White flight in the 1960s and 1970s that included the relocation of businesses to nearby shopping malls turned Silver Spring’s business district into a distressed area with many vacancies and neglected buildings and streetscapes.

Redevelopment efforts at the turn of the twenty-first century brought new capital, new buildings, and a new crop of residents who hailed from Central America, Europe, Africa, and Asia into Silver Spring. Some people, like local author George Pelecanos called it “gentrification.” Others, like Silver Spring’s historic preservation activists, saw it as a threat to the community’s heritage.

But what was Silver Spring’s heritage?

A Silver Spring Heritage Tour marker located on Georgia Avenue.

To the Silver Spring Historical Society, it is a narrowly defined part of Silver Spring’s past: stores, restaurants, movie theaters, churches, and homes built by and for the community’s white boosters and residents in the first half of the twentieth century. The society’s leaders have constructed a nostalgia narrative that – like the Jim Crow policies from the past – omits African Americans. “The heritage that the Silver Spring Historical Society … [celebrates] and aim to preserve is frequently at odds with the community's history remembered by older African American residents,” wrote a University of Maryland graduate student in a 2005 Ph.D. dissertation titled, “Imagined pasts, imagined futures: race, politics, memory, and the revitalization of downtown Silver Spring, Maryland.”

The bias towards a romantic, whites-only history is evident in the two books on about the community written by historical society founder Jerry McCoy and in the group’s historic preservation efforts. The latter has spilled over into public policy and planning through the designation of Montgomery County historic properties and in the Silver Spring Heritage Tour signs mounted throughout the central business district.

A historic resources survey of downtown Silver Spring memorialized the Silver Spring Historical Society’s nostalgia narrative by excluding African Americans from the discussion of Silver Spring’s history. The 2002 survey, conducted by a consultant under contract to the Montgomery County Planning Department, also did not identify or discuss sites associated with Silver Spring’s civil rights struggles in the 1950s and 1960s.

African Americans are similarly absent from the heritage trail. Only one of the signs mentions African Americans: a paragraph detailing a 1957 NAACP survey of business discrimination. Even that brief mention appears to minimize Silver Spring’s segregationist past. The organization, “conducted a survey of 18 cafes,” reads the text in one marker at the site of a former Little Tavern restaurant. “Six were cited for refusing sit-down service to African-Americans, including the Little Taverns in each community (they only offered carry-out)” [emphasis added].

Silver Spring in 2016 looks nothing like the Silver Spring of 1956 except in the community’s histories and the monuments to white supremacy, e.g., buildings and nostalgia narratives, those histories seek to preserve. Historians, public officials, and the general public should heed Loewen’s charge to ask why African Americans are missing. I did and though I didn’t like what I saw (or didn’t see), it opens up opportunities for discussions about equity and for exploring ways to correct the mistakes of both the distant and more recent pasts.