The Damage Intelligence Leakers Can Do

Day after day the intelligence leaks splash across our front pages, splattering sensational revelations about Russia’s perfidious election meddling or accusations about illicit contacts between Donald Trump’s aides and Russian agents. The frenzy of recent months has been extreme, but it is not entirely unprecedented. By considering an earlier uproar fueled by intelligence leaks we can gain insights into the motives of leakers and a broader perspective on the consequences of their disclosures of bits of classified information to politicians and journalists.

In March 1979, alarmed by Soviet-Cuban

cooperation in military operations in the Third World, National

Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski called upon U.S. intelligence

agencies to assess the size, location, capabilities, and purposes of

Soviet forces in Cuba by reanalyzing existing information and

increasing aerial surveillance of the island. Since the Cuban missile

crisis of 1962, the Soviet Union had kept thousands of troops in

Cuba, in part to train Cuban forces in how to use Soviet military

equipment. But the United States had not continuously kept close

track of the Soviet forces and Brzezinski wanted to check whether

there had been any violations of U.S.-Soviet understandings about

aircraft and submarines as well as ground forces.

In March 1979, alarmed by Soviet-Cuban

cooperation in military operations in the Third World, National

Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski called upon U.S. intelligence

agencies to assess the size, location, capabilities, and purposes of

Soviet forces in Cuba by reanalyzing existing information and

increasing aerial surveillance of the island. Since the Cuban missile

crisis of 1962, the Soviet Union had kept thousands of troops in

Cuba, in part to train Cuban forces in how to use Soviet military

equipment. But the United States had not continuously kept close

track of the Soviet forces and Brzezinski wanted to check whether

there had been any violations of U.S.-Soviet understandings about

aircraft and submarines as well as ground forces.

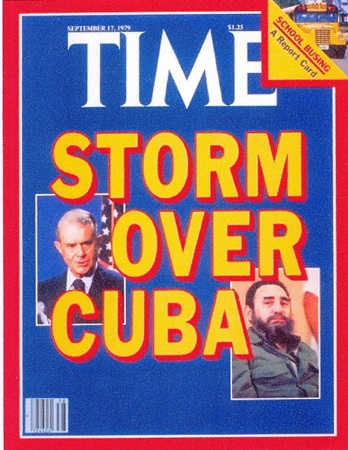

On June 18 in Vienna President Jimmy Carter and Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev signed the SALT II treaty, which placed limits on the nuclear arsenals of the two superpowers. Around the same time, the National Security Agency (NSA) believed it had discovered evidence of a Soviet “combat brigade” in Cuba.

After CIA Director Stansfield Turner ordered the NSA to abandon what he regarded as alarmist speculation, word of the NSA’s finding leaked on July 17 to Senator Richard Stone (D-FL). Stone was extremely sensitive to issues concerning Cuba because of the large, powerful Cuban-American population in Florida and because he faced a re-election campaign in 1980. An aide to archconservative Senator Jesse Helms (R-NC) also leaked the story to ABC News, which reported inaccurately that a Soviet brigade, “possibly as many as 6,000 combat-ready men, has been moved into Cuba within recent weeks.”

However, after Turner, Secretary of Defense Harold Brown, and Secretary of State Cyrus Vance offered assurances that there was no evidence of any substantial increase in the number of Soviet troops that had been in Cuba since 1963, the controversy subsided for a time. Then on August 17 U.S. reconnaissance satellites photographed Soviet troops, equipped with tanks and artillery, in a field exercise on a beach in Cuba. Before the new evidence could be fully analyzed and discussed by top officials (some of whom were on vacation), the story of a Soviet “combat brigade” of 2,000 to 3,000 men leaked to journalists on August 29.

Collusion between leakers and foes of SALT II went even further according to Nicholas Thompson, grandson of Paul Nitze, the most prominent critic of the SALT II treaty. In The Hawk and the Dove (2009), Thompson writes that in late August 1979 a senior CIA official confided to Nitze that the CIA had new evidence that the Soviet brigade in Cuba was not merely giving routine training to Cuban officers but was preparing for combat operations. With Nitze’s encouragement, the CIA official spread the story around Washington. Some in the press were also told that the Soviets had constructed a military airfield and were working on a missile boat base.

With such wild rumors swirling and fearing imminent publication of the story of the “combat brigade,” Under Secretary of State David Newsom decided to inform Senator Frank Church (D-ID), chair of the Foreign Relations Committee. Facing an election in 1980 and worried about being tarred as soft on the Soviet threat, Church decided to take a hard public stance: without considering how Moscow might react, he demanded the removal of the Soviet brigade, said SALT II would not be ratified until then, and postponed hearings on the arms control treaty.

Under pressure and thinking the USSR wanted SALT II ratification badly enough to make concessions, Secretary of State Vance declared at a news conference on September 5 that he would “not be satisfied with maintenance of the status quo in Cuba.” Two days later, while recognizing that the Soviet unit was “not an assault force” since it lacked airlift or sealift capability, President Carter nonetheless reiterated that “this status quo is not acceptable.” Brzezinski further inflamed the issue by telling a New York Times correspondent that the Soviet “combat brigade” in Cuba was part of a larger problem of Soviet aggressive activity and disregard for U.S. interests around the world.

Believing the “hysteria” and “hullabaloo” had been artificially manufactured by enemies of détente and was being used to make unjustified demands, Soviet leaders insisted (correctly) that the small training unit had been in Cuba for 17 years, posed no threat to the U.S., and would not be withdrawn or even modified. Seeing little left to gain from détente after hopes for SALT II ratification were dashed, Soviet leaders felt less constraint on their actions elsewhere. Although the Kremlin earlier had hesitated to intervene in Afghanistan, in December top leaders decided to invade the country, a move that put nails in the coffin of détente.

In mid October former National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy confirmed that Soviet diplomats had been right all along: the Kennedy administration had agreed in 1963 that a Soviet brigade could remain in Cuba at the same location where one was “discovered” in 1979. But by then the damage from the leaks had been done. As David Newsom observed in his compact study, The Soviet Brigade in Cuba (1987), “because intelligence is often partial or fragmented, its release can mislead; the account of the full circumstances may never catch up” to the sensational impression left by a leak.

If the intelligence about the Soviet unit had been fully analyzed before being conveyed to members of Congress or the press, and if the National Security Council and State Department had had more time to check their records of the 1963 agreements, it is very likely that the issue could have been resolved through quiet diplomacy and it is possible that the troubled SALT II treaty would have been ratified. Thus, the leaks may have altered the course of history in a profoundly negative way.

Some authors who have written about the 1979 controversy, such as Gloria Duffy and Stansfield Turner, have attributed the crisis to confusion, missteps, errors, and bureaucratic rivalry. Yet since the intelligence leakers chose to make unauthorized disclosures of information to influential figures like Helms and Nitze, who were known to be hostile to the Soviet Union and the SALT II treaty, and to Senator Stone, who could be expected to react in a highly emotional way, it seems likely that the leakers had political motives, not merely honest professional concerns.

While leaking had become part of the Washington scene by 1979, it has become a much bigger part of the political game in the 21st century. In recent months the leaking of unconfirmed and sometimes later discredited information has been so persistent that some national security experts worry about the potentially devastating consequences of a protracted war between the intelligence bureaucracy and the White House. Whether the leaks will destroy the prospects for improved American-Russian cooperation against international terrorism, nuclear proliferation, drug trafficking, and other problems remains to be seen.