Have We Missed the Big Picture of What Happened in Southeast Asia with Our Laser Focus on Vietnam?

Related Link HNN’s Full Coverage of the Debate over the Ken Burns/Lynn Novick Vietnam Documentary

It can be hard to tune out the vigorous debate over Ken Burns’s and Lynn Novick’s new documentary film series on the U.S. war in Vietnam. On the other hand, it is easy to presume that America’s leaders and people were from the late 1960s fixated on the violent excesses and failures of U.S. policy in Vietnam, unable to look beyond the all-consuming conflict.

In fact, American policymakers focused upon the broader Asian region even as their military campaign in Vietnam ground toward stalemate. Indeed, America’s containment strategy had approached Southeast Asia as an interconnected region from the very beginning.

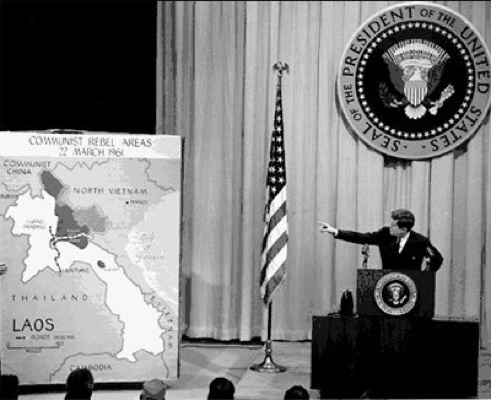

In 1949, Secretary of State Dean Acheson advocated “multilateral collaboration” with “like-minded” states in Southeast Asia to form a “great crescent” that ran southward from Japan, through Australia, and northwesterly to India. President Dwight Eisenhower, who coined the domino theory in 1954, sought to “build that row of dominoes so that they can withstand the fall of one.” In turn, Kennedy officials envisioned that the creation of Malaysia—merging Malaya, Singapore and the British territories of Sabah and Sarawak—would complete a “wide anti-communist arc enclosing the entire South China Sea.” U.S. military and economic aid to Thailand and the Philippines during the early decades of the Cold War, combined with copious amounts to Indonesia as General Suharto rose to power from the mid-1960s, consolidated this geostrategic arc encircling Vietnam and China. By September 1967, President Lyndon Johnson spoke boldly about the “great arc” of U.S.-friendly nations in the Asia Pacific that formed a ring around China.

When presidential aspirant Richard Nixon published “Asia After Vietnam” in an October 1967 issue of Foreign Affairs, his supposedly bold new vision for U.S. strategy offered more of the same. Nixon urged his readers to pivot their gaze to the “rest of Asia,” to see that Vietnam had “filled the screen of our minds; but it does not fill the map.” He recommended that U.S. policymakers “look beyond Vietnam” for an “extraordinary set of opportunities.” U.S. allies were “all around the rim of China,” he wrote. They formed an arc that stretched from “Japan to India,” ran through Indonesia’s “3,000-mile arc of islands,” and up into the Southeast Asia mainland. This arc, anchored by Australia and New Zealand, intimately linked to the United States, would “become so strong” that China must seek “dialogue” with the United States.

As President, Nixon apparently made good on these projections. In February 1972, he and Chinese leaders issued the Shanghai Communique to begin the process of normalizing Sino-U.S. relations. Senior Chinese leaders such as Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai were most eager for rapprochement with America. They faced an escalating Sino-Soviet rivalry, and their grip on power at home had weakened due to the excesses of the Cultural Revolution.

Looking beyond Vietnam reveals that the geostrategic arc of U.S. allies in Asia that made Beijing especially susceptible to Nixon’s overtures. By 1969 Zhou Enlai openly expressed frustration that China was “encircled” and “isolated.” The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), founded in 1967, espoused a thinly-veiled pro-U.S. bent. And ASEAN joined other anticommunist regional organizations, such as SEATO and the Asia Pacific Council (ASPAC, formed in 1966) that in Beijing’s view had already ensconced the wider Southeast Asia within the U.S. orbit. In time, Zhou would even share with National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger that he believed the “institutions” for containing China in Southeast Asia were “more numerous than in any other area in the world.” Regardless of what Beijing could claim to have done for Hanoi and the Viet Cong’s campaign against the U.S. war machine, its prospects for expanding Chinese influence were paltry beyond Indochina.

Though Burns’s and Novick’s new series compels us to revisit the ill-fated America war in Vietnam, U.S. policy failures in Indochina must be situated within the larger regional context, placed in contrast to Southeast Asia’s overall pro-U.S. trajectory. Put crudely, America lost in Vietnam but won the Cold War beyond it.

Of course, this brings little comfort to the victims of the American war in Vietnam and those who survive them. The U.S. triumph in wider Southeast Asia cannot erase the tragedy of the millions of Vietnamese and tens of thousands of U.S. servicemen who perished in the conflict, not to mention the bloodbaths in Cambodia and Laos that unfolded alongside.

Nor should it. Rather, looking beyond Vietnam reveals that America’s victory came at an even higher price. U.S. allies in the wider Southeast Asian region seized and maintained power variously by coups, crackdowns and massacres, aided and abetted by the U.S. or Britain. These allies upheld the “wide anticommunist arc” that outlasted American defeat in Vietnam; that predated Lyndon Johnson’s decision to commit U.S. troops to Vietnam; it begs only more questions of the war that Burns and Novick insist was begun in “good faith by decent people, out of fateful misunderstandings.”

Copyright Wen-Qing Ngoei